Virtually all music disciplines share one thing in common: The movement of sound. This of course involves time and rhythm, even in the most seemingly out-of-tempo and arhythmic music.

It could be said that the improvising musician’s skill lies in having the ability to sponataneously turn artistic impulses into ideas that manifest themselves into moving sound.

Students of improvisation (from beginner to pro) approach this reality in various ways. Some spend huge amounts of time memorizing stylized patterns, licks, solo transcriptions and so forth. For sure this leads to maintaining and cultivating the ability to “move the sounds” to create the music.

If you’re working constantly on these things, more music comes out of you when you improvise. This is largely because you know “what to play” as you improvise a solo.

If you approach improvisation this way, your solos will most likely sound consistently controlled, melodically sound, stylistically accurate, cogent, and full of clear intention. All good things, without a doubt.

But if you ever want to get to a deeper level of playing, a more personal level, you need to shift your emphasis from “what to play”, to, “how to move”. I’m talking specifically here about taking a step back from working with pre-formed ideas (licks, patterns, etc.) and instead aiming at working with the materials of the music on a much broader level. Diving deeply into the materials of the music to expand your ability to move the sounds with ever increasing spontaneity and surprise (both to the listener and to yourself).

Now, it could be argued that the memorizing of licks, patterns, transcriptions, etc., leads to all this. To a large degree this is entirely true. Studying these things to the point of absorbing their logic, and ultimately transcending them, is a worthy aim for the serious improvising musician, and can set a foundation strongly rooted in the tradition of the art form.

But if you want to significantly increase your chances of playing something fresh each time you improvise, you’ve got to start lessening your use of the pre-packaged stuff. You’ve got to leave the formulas alone and start looking toward two broader targets: Increasing your rhythmic imagination and control, and re-thinking and expanding how to organize pitches.

In an eye opening interview with saxophone legend, Joe Henderson, by Mel Martin (himself a formidable and highly gifted saxophonist, improviser and composer), Joe addresses this question of “formulas” quite well:

Mel Martin: Everybody wants your formula. How many students have come to you and said, ‘Joe, what are those patterns?’

Joe Henderson: And those are the kind of students I don’t take. I want to effect the part of their brain to create these things. When you think about this in a certain way, there is no formula.

Mel Martin: What they hear as formula is actually something you created spontaneously out of all the resources that you have at your command. (Brilliant!)

Mel Martin’s comment absolutely sums up what I’m talking about here. Joe could move the sounds differently, gloriously, surprisingly, every time he played. Melodically, harmonically and rhythmically magnificent without exception.

Here are some things you can do to help you shift your focus from specifically what to play, to playing (again quoting Mel Martin from his comment above) spontaneously out of the resources that you have at your command:

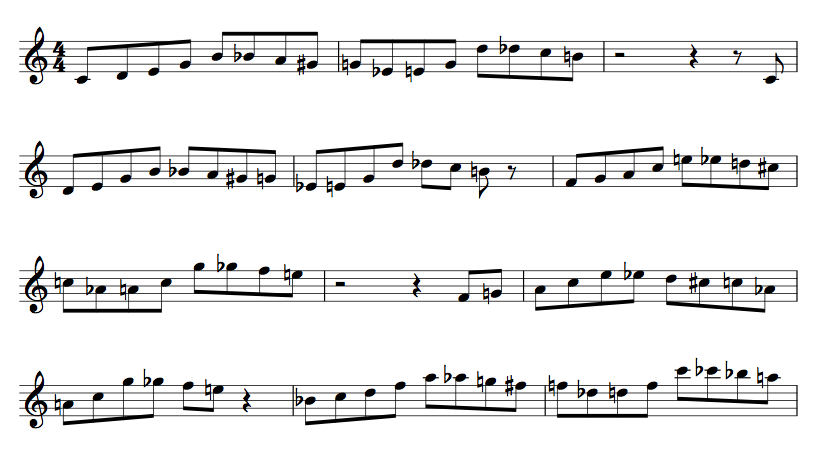

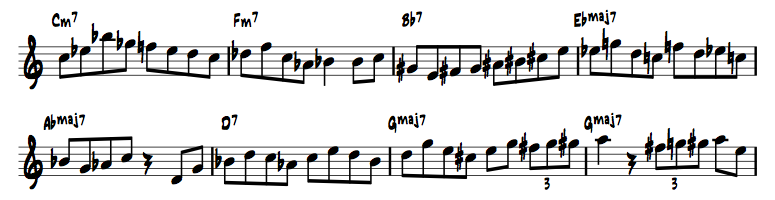

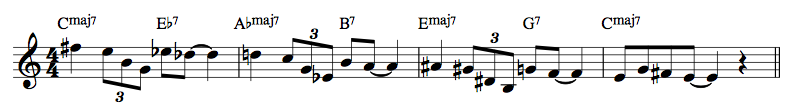

- Make rhythm primary-Rhythmic variation literally has no limits. It is the thing that makes music, music. More so than anything else. It is the language of the universe. Yet it’s amazing that many jazz improvisers have a rather limited rhythmic conception and base from which to draw ideas. Start moving away from practicing all your tonal material in symmetrical patterns of eighth-note, sixteenth-note and triplet patterns. Aim for three things: Polyrhythms (e.g., 5 eighth notes over 2 beats), polymeter (e.g., organizing eighth note melodic patterns in 4/4 to imply 3/4) and rhythmic displacement. Becoming masterful at rhythmic displacement is a key element in all this. Take any melodic idea you have in mind and practice starting it from various places in the measure (e.g, up beat of 1, down beat of 2, upbeat of 2, etc.) Gaining this kind of rhythmic control and imagination will consistently help you find new ways to move the sounds. And of course, practice in odd metered time signatures. Every day. Break that “4/4” predictability (though if you practice this way often enough, your 4/4 playing goes to a whole new level of creative possibilities).

- Turn everything you practice into melody-Rather than playing mindless scale patterns from the bottom of your range to the top, create patterns and ideas that sound melodic to you out of these scales (or chords, etc.). Make the organization and movement of the notes be always interesting and pleasing to you aesthetically. Work toward using your musical materials in ways that connect you to your creative, expressive self. Develop your technique to become the servant of that expression.

- Rethink tonality-There really is no such thing as “mastering” the scales, chords and intervals. There are always new ways to organize this material. This was a big part of Joe Henderson’s approach. A great way to explore familiar tonalities in unfamiliar ways is to extract and regroup. For example, you can take a symmetrical, non-tonal scale like the diminished scale and organize the notes into tonal (major and minor) triad combinations that still have the tensions of the diminished scale, but have a very different color. Thought, curiousity and exploration are all you need to find seemingly limitless new tonal ideas.

- Broaden your sense of time feel and articulation-If you’re a jazz musician, stop swinging everything. You can always go back to that feel anytime you want. But getting stuck into one time feel sort of locks your brain into thinking one way about organizing and moving the sounds.Try improvising over a song or a set of chord changes without your swing feel, and you’ll find many new ways to organize and move the notes. Same with articulation. Practice improvising with many different specific articulation patterns. It’s especially helpful to practice an articulation in an odd rhythmic grouping (e.g., 5) against an even time signature (4/4). Yet another thing you can do to really help broaden your rhythmic imagination.

- Improvise slowly-I can’t emphasize enough the importance of slow improvisation (I’ll be writing an article about this specifically in the near future). By improvising on tunes, changes, themes, modes, etc. at very slow tempos (I’m talking about quarter note equals 50-70) you give yourself the chance to discover many new ways to work with your musical materials, many new ways to move.