Learning to improvise music means learning to respond immediately to the stimuli of the moment (time feel, harmony, song form, other players, etc.) in such a way as to produce cogent, sincerely expressed music. There’s lots of reflexive activity going on here. Stuff seemingly below consciousness.

If you ask many highly gifted and accomplished improvising musicians what they’re thinking as they improvise, you’ll likely be met with something like a blank stare.

Then, “I’m not thinking of anything. I’m just playing.” (this and its variations are what you might often hear.) And though it’s not true that they’re not thinking, it is very likely true that they are not self-conscious in the improvisational process.

More specifically, when an artist is making music spontaneously, there is little conscious thought of the materials of the musical medium: pitch, time, rhythm, harmony, etc.

In truth, the accomplished improviser has transcended these materials when improvising. This only occurs through considerable discipline, reflection and time commitment. It’s as if the improvising artist is practicing mastering these musical materials in order to forget them and just get down to the business of making music.

And I think that that’s the entire aim of practicing diligently: To transcend the self-consciousness of acquired skill.

For sure, the same thing can be said about great interpretive musicians. They, too, have to transcend their skills to get to that high level of personal expression.

But what makes this especially relevant ti the process of improvisation is that to improvise you have to supply the actual “text and flow” of the composition itself (what you actually improvise) in the moment.

You have perhaps even more balls in the air to juggle: Note choices, rhythm, harmonic color, the length and shape of the phrase, the overall “story” of your improvisation, pushing or following…Not to mention the response and connection to those with whom you’re playing.

Whenever I hear a less than satisfying improvisational soloist (particularly in jazz played over harmonic forms), I always notice this one common characteristic: I can always too easily hear what the improviser has been practicing (the patterns, licks, etc.)

I don’t want to hear that. I want to hear music. I want to hear expression. I want to share a journey. I want to be surprised.

In short, I don’t want to hear the musician in the practice room. I want to hear the artist in the moment.

And I’m not alone here. Whenever we hear the practice room musician, we are hearing a disconnected, undeveloped, somewhat shallow form of self expression. That’s not necessarily bad. In fact, it’s probably necessary in the growth cycle of the emerging artist. Passing from ignorance and lack of skill, to self consciousness, and finally (if we’re fortunate) to self actualization and deep expression.

Yet you’re probably never going to go out and buy the latest recording of a jazz musician whose primary focus is on trying to show you all the hip ideas she or he has practiced in the past two or three weeks . The fully realized artist has no interest in showing you this type of sophistication. The aim is much deeper. And musical sophistication is only useful if it serves the bigger goal of personal expression.

So if you wish to aim high, as the great improvising artists have, Aim toward transcending your musical skills and knowledge. Here are a few things to keep in mind to help you:

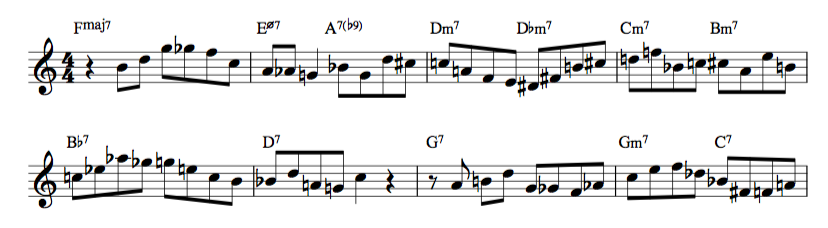

- Aim for deep mastery-Jazz piano genius Kenny Werner addresses this perfectly in his book Effortless Mastery. Rather than continually adding new, only partially internalized material (new scales, new chord shapes, tunes, etc.) to your practice repertoire, consider spending a great deal of time mastering the most basic material. If it’s a set of scales, for example, work on an endless amount of patterns and variations based upon the notes of the scale. You’d be surprised at how exotic and beautiful a major scale can sound if you explore and find the interval combinations. There’s no limit to the beauty of diatonic music.

- Don’t keep practicing what you already know-Once you have really mastered a particular pattern (I mean really mastered it) stop practicing it. Trust that it (and more important) its variations will organically reveal themselves in your playing as a part of your true musical gesture.

- Allow time-When you practice new material, you must consciously use it as you practice improvising. But on the bandstand, don’t give it a thought. Trust that as time goes by, all the things you’ve worked on will contribute to your improvisations in a natural and beautiful way.

- Follow your ears-Make sure you can easily sing any idea, scale, chord or interval shape that you’re practicing. Go back and forth between singing and playing. You strongly internalize your musical materials this way, and take them out of the self conscious realm. You play what you hear, not just what you think.

- Practice not knowing-Put yourself into situations where your improvisational skills don’t easily fit in. For example, if you’re primarily a straight ahead jazz player, try improvising with skillful “free jazz” improvisers. Even if you never want to play “free jazz” you’ll have a great chance to see if you can make music without your prefabricated arsenal of musical ideas. (It’ll make you a much more spontaneous, adventurous, powerful jazz improviser, I promise!)