When is a musical idea melodic? What makes it so? These are questions that musicians could debate for an eternity. If you’re an improvising musician these questions are particularly pressing because they not only reflect how you play, but also, what you feel, hear and imagine. They bring your deepest aesthetic impulses into the light for all to know.

There is a conventional wisdom in jazz circles that certain artists were/are more melodic than others. For example, many would say without a doubt that Stan Getz was a far more melodic improviser than John Coltrane. (These very same folks might revere both artists equally, or might even prefer Coltrane over Getz.)

I personally don’t think Stan Getz was any more, nor less, melodic than John Coltrane. I think both of them provided great melodic content in their respective improvisational work. It’s just that their melodic conceptions were different from one another. If Coltrane wasn’t melodic, I don’t think he would have ever touched people as deeply as he did.

But you might say, “What about Coltrane’s ‘sheets of sound’? What about all that harmonic and sonic exploration? What about all those patterns? What about all those notes he played?”

To me, that was the melodious John Coltrane. Why? Because Coltrane improvised with the very quality that makes all great improvisers sound melodious to me: Clear intention. He simply took the materials of music he’d studied and let them come through him in purposeful self expression.

Sure, Coltrane was always pushing the bounds, working things out on the spot as he improvised. He even apologized in an interview once that his music wasn’t “more pretty”. But like human speech, where there is intention, there is meaning (even if it’s not so apparent to everyone listening).

So I guess the question is, How do you hear his music? Do you hear melody?

In a rather remarkable book by musicologist, composer, and advocate of contemporary music, Nicholas Slonimsky, titled The Lexicon Of Musical Invective, you can find evidence that melody doesn’t always sound like melody when people first hear it.

In The Lexicon, Slonimsky presents various reviews by respected critics from different periods in classical music. Here you can find such great composers as Beethoven and Brahms being skewed for their lack of melodious work. “Barbaric” is the way one critic described Beethoven’s conception of melody.

Yet nowadays you’ll be hard pressed to find anybody (even if they don’t like classical music) who would say Beethoven’s work is not melodious. They might call it boring, but they could still easily hum the themes to his symphonies.

When I first started playing jazz in the 1970’s I remember being dumbstruck when meeting several older jazz fans who thought Charlie Parker permanently ruined the music, because he destroyed any semblance of melodic expression. “I only like jazz that’s melodic”, said one of them. (Charlie Parker not melodic!?! Seriously!?!)

All melodic content follows certain laws of nature. There is the building of tension, the sustainment of tension, and the release of tension. Yet there is no order, formula or rule that this necessarily follows. Even the perception of these elements is hightly subjective to the listener. But it rarely is to the great improviser. As time goes by, it’s often a matter of the listener finally being able to hear the melodious intentions of the improviser.

One of my favorite jazz improvisers of all time is the tenor saxophonist, Warne Marsh. I always find it interesting what other musicians say about Warne when they hear him for the first time. If they don’t like him, then of course it’s because “he’s just playing notes, not making any melodic sense”. Or, “his sound is just weird.”

But even some of the folks who respect Warne don’t find him to be a particularly “melodic improviser”.

One of my dear colleagues once told me, “His harmonic and rhythmic explorations were incredible..not particularly melodic, but highly interesting, and clearly demonstrating a high degree of discipline and skill.” I had to chuckle to myself when I heard that, because to me, Warne played nothing but melodies. That’s sort of all he did, letting one beautiful idea influence and flow into the next. Sometimes at lightening speed, but melodies no less.

Maybe the role of the great improviser, of the innovative improviser, is to lead us into new ways of hearing melody, of comprehending meaning in this human endeavor.

So how can you become a more melodic improviser? Simply clarify your intentions so you can broaden your own definition of melody. Here’s two things you can do to help you with this:

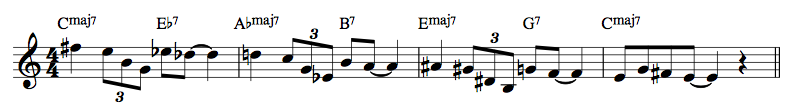

First, stay on a continuous quest to explore the elements of music (rhythm, harmony, tonal organization, intervalic shapes, genres, forms,etc.) and to expand your conception and command of them. Always strive to find new ways to organize the musical material…new patterns and new approaches. Build your own language in a way that makes melodic sense to you.

Second, learn to clearly hear everything that you practice. Make singing a big part of your daily practice. Every time you start to study a new pattern of any sort, make sure you spend enough time learning to sing it easily, readily and clearly. Strive to hear the patterns you create as melody, as something you draw upon with intention. As I get older, I find myself singing more and playing less when it comes to exploring new material.

So let’s keep those questions about “what makes a musical idea melodic?” open to exploration and interpretation. And maybe, ultimately something sounds melodic because it sounds familiar enough to seem so. No matter the reason, aim for learning to play whatever you play like you mean it.