Many musicians define themselves (or could otherwise be categorized) as being primarily interpretive musicians, or primarily improvising musicians. In other words, their main creative impulses lie either in interpreting the musical thoughts of others, or in composing their own music right on the spot. When you put it this way it seems like an either/or situation. You are, or you aren’t. Or you’re both.

But is it as simple, as black and white, as that? To me, it begs the question, “What is improvising?” I don’t doubt that lots of musicians (and critics) have very clear and ready answers for that question. Strangely enough, I don’t.

I do know that when I’m improvising, a very unique and beautiful process is taking place. For me, it’s a form of meditation, a way of finding my way back to my own internal temple of peace and joy.

I also know is that I’m making countless creative decisions (almost unconsciously) moment to moment in order to let something release from within me. But it doesn’t feel to me as if I’m creating the music, creating the flow of pitches and rhythms. It’s more like I’m just following them.

These days, I spend about half of my music listening time with classical recordings. Interpretive musicians at play, as it were. One of the things that thrills me the most is to hear the stunning differences in interpretation between various artist performing a given piece.

Even though these artists are only “interpreting” the music, I’m amazed at the seemingly endless creative choices they’ve made with the music. They, too, sound as if the music is rising up from within them, being created in the moment. It sounds improvised to me.

When I attend a great classical concert performance, it seems as if the artist is making some of these choices moment by moment, feeling the unfolding pulse of the music. Risks are being taken. The sound of surprise.

And ironically, I can go to some jazz performances where the so-called “improvised music” doesn’t sound or feel to me at all improvised. It sounds canned and far too premeditated. No risks are being taken. The sound of craftsmanship, skill, taste, cogency….but not really the sound of surprise.

So it got me to thinking, is the act of improvisation an absolute thing, or is it a direction on a path that can be followed? And are dynamic interpretive musicians, to some degree, improvisers or simply creative in another way?

If there is a continuum, a direction, toward improvisation, I think it mirrors closely our tendency toward verbal communication. It’s ironic that sometimes in the most potentially heartfelt moments (like at a wedding, funeral, or graduation ceremony) some speakers can stand up and say something that sounds absolutely pre-packaged, as if it were lifted right off of a Halmark greeting card. “I wish you health, long life, happiness and eternal blessings…..”

Nice sentiments, for sure, but are they genuinely expressed and created specifically in the moment for that occasion? More important, do these sentiments rise from that creative, emotional well within? Is it improvisation, or a regurgitation of something previously heard?

Don’t get me wrong, I think these kinds of sentiments are often sincere, they’re just so unoriginal, and thus sound startlingly impersonal. Contrast that to somebody who gets up, with no public speaking polish or experience, and speaks from the heart, improvising a moving speech. Speaking personally. The sound of surprise.

I think we’ve all had similar experiences when we’ve heard musical performances. You can’t plan magic. It just happens, or it doesn’t.

In the realm of modern jazz improvisation, there is a continuum from the mainstream, to the more progressive, to the (for want of a better word) avant-garde. Yet within each of these approaches, styles, genres…whatever you want to call them, there are degrees of true improvisational originality.

I tend to lean toward the left when it comes to jazz and improvised music, yet I’ve been on the bandstand with some really “free” players who turn the entire set into a Hallmark greeting card moment.

I’ve also experienced creative transcendence and spiritual power playing with, I guess what you might call mainstream stylists, sometimes just playing standards. To me it has less to do with the music than it does with the musicians. (I’ve also experienced the opposite phenomenon many, many times.)

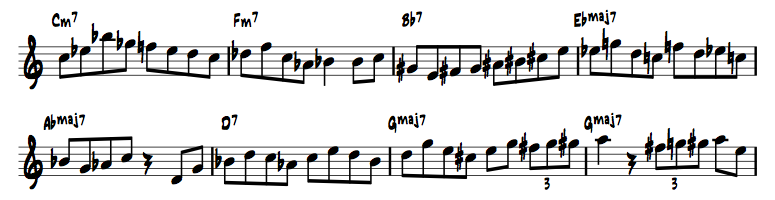

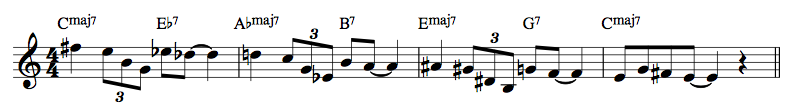

If you transcribe or read through enough Charlie Parker solos, you’ll find he had many pre-packaged musical ideas (licks). On the other hand, if you transcribe a Sonny Rollins or Joe Henderson solo, you’ll be harder pressed to find a “lick”. Take down a Warne Marsh solo or two and I doubt that you’ll ever find anything like a lick.

Does this mean I think that Rollins, Henderson and Marsh were superior improvisers compared to Parker? Not at all. Parker, in my opinion was as spontaneous as they come. That music just hits you right in the soul when you hear it. It still excites me every time I listen to it.

It’s just that Charlie Parker had codified some of his own musical thinking into components. Yet he always created surprise by stepping in and out of these components, naturally, sincerely and spontaneously. And in practically any of his solos, you’ll hear absolute, first time creation of many musical ideas. The sound of surprise.

What makes Charlie Parker ultimately brilliant is how he combines these codified ideas, how he organizes them in any given solo. The variations and permutations he makes, that he discovers for the first time as he plays. Creative decisions being made by the hundreds in each solo. Again, the sound of surprise.

Warne Marsh, on the other hand, had a different approach, a different impetus with the material of improvisation. He had deeply studied and absorbed solos from Lester Young, Parker, and other greats. He’d spent a huge amount of time working with patterns, inversions, substitutions, rhythmic freedom and displacement.

But his aim wasn’t to codify his work into concrete, packaged ideas. In fact he was careful not to. His brilliance lay in the spontaneous manipulation of his musical materials as he followed his muse, rather than in the reorganization of codified ideas. Creative decisions being made by the hundreds too, just in a different way. The sound of surprise.

So where are you on the improvisational continuum?

Do you have tons of licks memorized in all keys so that you’re never at a loss for what to play? So that you never the possibility of sounding wrong or unsure? Or do you let yourself find the music anew each time you play, without any safety net? Or are you somewhere in between?

Wherever you are, one thing is for certain: to improvise more deeply, more genuinely, you need to give up the idea of playing it safe, of always sounding like you wrote out your solo. In short, you have to let go of the idea of always knowing.

I remember hearing a story by Chick Corea about Thelonious Monk. Chick’s band was on the same bill as Monk’s band at some concert in New York. Monk played first. The band starts with the iconic, “Rhythm-n-ing”. They play a stunning performance. Chick is astounded. Then Monk launches into the second piece of the concert. Rhythm-n-ing again. Chick says the second version is nothing at all like the first, all the musicians playing completely differently (yet equally brilliantly) than on the first version. And then into the third version of the same piece. Monk’s band ends up playing “Rhythm-n-ing” four times, each version stunningly different than the previous. That’s the entire set. Chick Corea is completely edified. (I was edified just hearing the story for the first time!)

In my opinion, that’s improvising at the very top of the creative spectrum. That’s the sound of surprise.