The art of musical improvisation involves imagination and ability: An unfettered muse supported by the specific skills necessary to turn creative impulses into clearly expressed ideas. It is the discipline of musical composition carried out moment to moment. In real time.

Because of the “real time” demands of improvisation, it’s natural for our brains to find patterns to rely upon to simplify the task. This is both good and bad. Good because it leads to connectivity, cogency, fluidity. Bad because it can also lead to us getting stuck playing many of the same things the same way over and over again.

As I listen to many jazz improvisation students, I’m many times struck by the lack of rhythmic imagination in their improvisation. In jazz pedagogy there is, in my opinion, too often an over emphasis on pitch studies (harmony, scales, passing tones, tensions, resolutions, etc.) at the expense of rhythmic studies.

Don’t get me wrong. I think it is absolutely essential to gain control over this vast amount of tonal material in order to improvise deeply, effectively and personally in the realm of modern jazz. (Lots to practice!)

Yet it is the energy of movement that turns pitch choices into music. That’s where time and rhythm come in. But too often I hear jazz improvisers playing the same rhythmic patterns, the same predictable accents, with far too much of an cadential emphasis on the form of the song they’re improvising over.

When I give a first lesson to a student of improvisation, I’m listening for many things, trying to get an idea of where they’re at with their skill and conception. Whenever I hear a student that can play with a considerable amount of fluency (holds the song form and makes the changes with relative ease), but a rather limited rhythmic conception, I always ask how he or she practices the materials of the music (scales, arpeggios, intervals and other patterns).

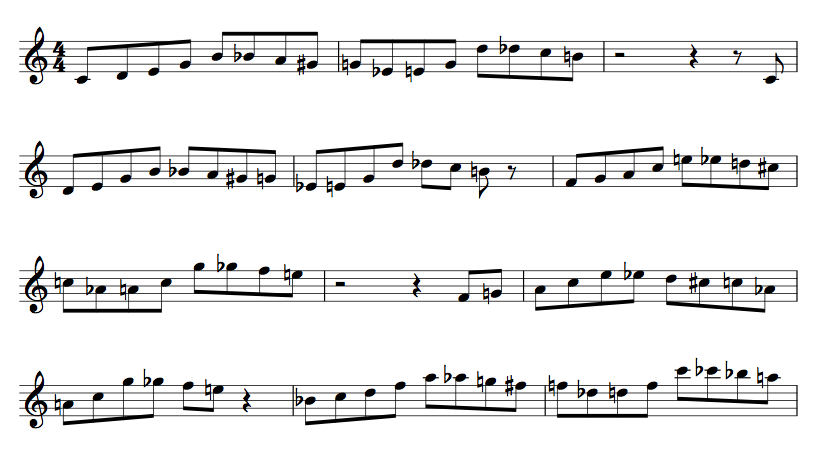

What I usually observe as the student plays through scale, arpeggio and other exercise patterns is far too much respect to a “4/4” kind of symmetry. Everything fits nicely into the bars and ends on the downbeat. For example, secondary triads in major keys (C major here as an example) might be played as follows:

As you can see, there is a metric grouping of 4 notes emphasized by virtue of the tonal pattern. (I use accent marks here to outline the rhythmic subdivisions). There’s nothing wrong with practicing this pattern in this manner, but you must realize if you (or my student) were to do so exclusively (or even primarily), you’d be seriously limiting how you might use this intervallic movement in your improvising. Lots of emphasis on the downbeats, and lots of emphasis on the “box” of the four bar pattern.

In essence, you’d be depriving yourself the opportunity to develop your rhythmic imagination and control to its fullest. No matter how much harmonic material you get under your fingers and into your ears, you’d be missing out on so many movement possibilities.

So a very simple thing you can do in your practice to open up your rhythmic imagination is to avoid putting all your scale, arpeggio and interval patterns in these neat little boxes.

Here are three techniques you could employ to make the pattern from above a bit more interesting and challenging while still maintaining the continuity of the line:

1. Rhythmic displacement-You can move the starting note of the pattern to different places in the bar. Here are two examples:

In the first example I displace the pattern by one half beat by starting on the upbeat of one. This kind of playing “turns the time around” so that the downbeat sounds like the upbeat. The second example has the pattern displaced by one full beat. You could go on and displace the pattern on each part of all four beats, learning to feel the movement of the pattern from many different angles.

2. Polymetric modulation-By slightly modifying the notes in the pattern you can imply different meters. (I’ve used accents to clarify.) Here is a 3/8 over 4/4 pattern:

I’ve modified the pattern above by simply omitting the fourth note (the repeated 3rd of the triad) of each group.

Below is a 5/8 over 4/4 pattern which I create by adding a fifth note to each previous group of four notes (the root of each triad):

And here’s a 7/8 over 4/4 pattern (accents on groups of 4 and 3). This pattern is a bit more complex, but easy to understand. I simply remove the fourth note (again, the repeated 3rd of the triad) from every other previous group of four notes.:

(If you’d like to explore polymetric modulation and rhythmic displacement in a thorough, methodical way, please consider my eBooks, Essential Polymeter Studies in 4/4 for the Improvising Musician, and Rhythmic Dissonance.)

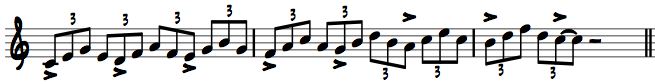

3. Rhythmic modulation-By placing a 4-note grouping in the pulse of a triplet, you can create an interesting kind of rhythmic tension:

You could also use the same kind of metric modulation to with the other modified patterns from above. There are many, many ways to vary this simple triad pattern.

And I haven’t even touched upon the possibility of adding more variety by combining rhythms (mixing eighth notes with quarters, sixteenths, using ties, rests, etc; that’s a topic for another article). As I mentioned earlier, I wanted to show you here how to play patterns with a continuous pulse.

So try some of these technique next time you practice your scales, arpeggios and intervals. (If you like to play licks and other patterns you’ve learned from transcribing solos, you could also practice them in this more rhythmically multi-dimensional way.)

Of course, you should always use a metronome to check your accuracy and control. Practice each pattern with the metronome clicking on each beat, and with the click only on beats 2 and 4 (backbeat swing feel).

And if you’d like to approach these kinds of variations and explorations in time, rhythm and meter in a more methodical, challenging and comprehensive way, you might consider my e-book, entitled Rhythmic Dissonance.

Make it your mission to find new ways to work out your melodic material in a less predictable way as you expand your tonal language.

Having the ability to call upon these rhythmic devices and learning how to “land on your feet” (always knowing where you are in the bar) will vastly improve your spontaneity and control as you improvise. If you make this a regular part of your practice you’ll really surprise yourself with how you can think and move in new ways. Imagination supported by skill.

Here’s a video performance of the late, great, Warne Marsh playing Body and Soul. Listen to how he floats and subtly shifts the cadences of the song and beautifully creates and resolves rhythmic tension against the steady pulse provided by the rest of the band. A master at work. Enjoy: