No matter how much you study, analyze, understand or memorize, you still need good ears to improvise music with fluidity and authentic self-expression. You have to be able to imagine and carry out your internal aural impressions in real-time.

Developing your ear is of prime importance, and is something that a serious improviser spends a lifetime cultivating.

As I reflect upon how I work on my ear, I’ve come to realize that no matter what I’m working on, I’m always developing one of three skills:

1. Recognition

2. Retention

3. Sensation

I’d like to talk a bit about each one of these skills, and what you can do to improve them. Keep in mind that the they are inseparably connected, and work together to help you to turn imagination into sound.

Recognition

This is where it starts for many musicians: learning to recognize intervals, scales (and their modes), chord qualities and inversion, chord sequences, harmonic tensions, melodic patterns, etc.

I cannot stress the importance of this foundational work enough. The better able you are to connect the various elements of music to your ear and intellect, the more melodic possibilities you’ll find when you improvise.

It’s best to start from the simple, and build your skills toward the more complex:

- Intervals-Melody is nothing but a series of intervals, so mastering intervals is essential. You should be able to recognize any interval in all forms (ascending and descending melodic, both within the octave and beyond the octave; and the notes of the interval played simultaneously). You need to do this work to the point where you don’t even have to think about which interval you’re hearing. Prepare to spend a good deal of time working with this, and allow periods of review, even after you think you can easily hear, sing, or play back on your instrument any interval. (It’s crucial that you practice both singing back and playing back the intervals you test yourself with.) There are lots of great resources to help you with this now, including some terrific smart phone apps that are very thorough and inexpensive (or even free!)

- Scales-The material of much of the intervallic sequences that constitutes melodies comes from scalar material. To start, you need to be able to recognize and sing, major and minor scales in any key and from any inversion (mode). Then work towards the same competency with symmetrical scales: diminished, augmented, whole tone, as well as any other scales that either strike your fancy or challenge your ears.

- Chord qualities-Much of the structural and melodic impetus of improvised melodies in the jazz tradition comes from the harmonic form. Therefore, it’s a good idea to master not only understanding the theory of chord construction and harmonic movement, but also, to be able to sing and recognize the various chords in their inversions. Again, start from simple (major and minor triads) and move toward complex (seventh, ninth, eleventh and thirteenth chords, sus7, altered chords, etc.)

- Tension qualities-This is related to the skill above. Specifically, learning to recognize and sing the various notes of of any given chord relative to the chord itself. For example, hearing/recognizing/singing the 7th of the dominant seventh, or the raised 11th over a major 7th chord. Tasting Harmony, A New Approach To Ear Training, by Greg Fishman, is an excellent resource for this.

- Chord sequences-Going from the smaller picture of hearing chord qualities to hearing and recognizing chord sequences is fundamental to your freedom of expression. Learning to recognize ii-V-I movement, with all its modulations and voice-leading resolutions, will help you memorize (and retain what you’ve memorized) when you learn standard songs or other harmonic forms. It will also significantly help you play by ear when you have no idea of the chord changes. A simple but effective way of working on this is to take chord changes off of a recording by ear. Use your instrument, your voice, a piano…anything to help you. Connect what you hear, sing and play back, with your intellect (theoretical understanding). Start with easy songs (could even be simple, children’s songs) and move on to standards, bop tunes, into modern jazz compositions.

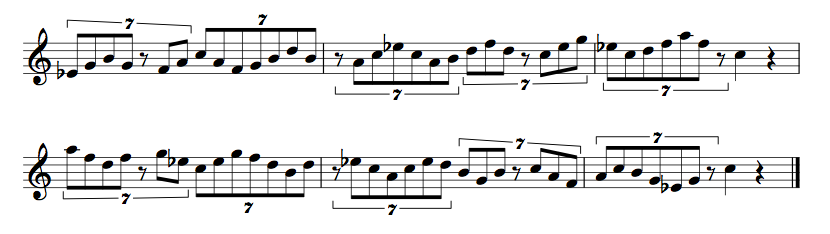

- Melodic patterns-Learning to recognize and recall common melodic patterns and licks will shorten the road from your imagination to your improvisation. Transcribing jazz solos of master improvisers is highly effective practice for this. It’s also important (and very helpful!) to play as much as you can by memory when working on patterns of any sort. Once you understand the structure, or formula of a particular pattern, and can sing it clearly and easily, strive toward playing it by ear. (Don’t write it out to help you learn it.)

If this seems like a lot of work, understand that it is, and that it’s something that you work toward improving and growing for the rest of your musical life. Nobody has a “finished” ear.

Even Charles McNeal, who is arguably one of the most prolific transcribers of jazz solos (he has an AMAZING ear and is a tremendous jazz saxophonist!) will tell you that he can transcribe the more “bop-oriented” soloists much faster than he can the “modern cats”. Why? Because the language of bop is more familiar to him. (It is for that reason that Charles welcomes the challenge of transcribing more modern players. He wants to constantly improve his ear.)

Retention

Once you are able to recognize intervals, scales, chords, etc., you need to be able to keep the aural impression of these elements alive in your imagination as you play (this is especially crucial in transcription and memorizing patterns/licks by ear).

Neuroscientists call this ability “working memory”. Specifically, the capacity to keep multiple bits of information available to your thinking simultaneously. (As an example, it’s easier to hold two notes in your aural memory than it is to keep an entire unfamiliar melodic pattern.)

One of the frustrations with some students of jazz improvisation is with retention. They can recognize intervals easily; they can recognize scales and chord qualities and tensions, as well.

But have them play a simple melodic sequence back by ear and they sometimes fall apart. Why?

Well, it’s often because they are not continuously hearing the melodic sequence in their imagination as they try to recall it. Often they’re getting stuck on one interval at a time, and before they know it, they’ve completely forgotten what it is they originally heard.

If you get frustrated with this, here are three things you can do to help as you play back melodic patterns by ear:

First, make sure you clearly hear the entire sequence and can “repeat” it back in your memory. Listen, listen, listen, as much as you need! (Shorten it into smaller sections if need be and work with one section at a time.) It is absolutely essential that you can internalize the material and can hear it in your imagination without singing or playing your instrument.

Second, now sing the sequence several times to affirm the accuracy of your aural imagination. If it is part of a transcribed solo, make sure you are singing the inflections, articulations, dynamics, etc. Make it come to life in your imagination.

Third, play it back on your instrument (again, with all the inflections). If you know your intervals and have sung the sequence lucidly, you’ll have no problem.

This is a skill (retention through working memory) that you can (must!) continually develop. My guess is that somebody like Charles McNeal has a very highly developed working memory from all the transcription work he’s done.

Through regular practice, you can get so you can repeat entire phrases (and even sections of transcribed solos) back as easily as you used to be able to play back 3 or 4 notes. Practice working on longer and longer patterns, always keeping the aural impression within your reach.

Sensation

The ultimate aim of using your ears should be to use them instinctively. You want to follow your ear, not your intellect. (The great improvising saxophonist, Warne Marsh, would sometimes chide his students as they improvised by saying, “I can hear you thinking.”)

This is where being open to your sensory experiences can be very helpful. Learn to imagine the feeling of the sound in the instrument, of the resonance and color, as you move from one note to the next when translating something back by ear. For example, if you play a wind instrument, “taste” the sound from one note to the next.

If you play the piano, learn to sense how you move and where you go spatially as you play back what you’ve heard or imagined. I can often easily find something by ear on my saxophone just by fingering (not blowing) what I imagine the sequence to be. That feeling of movement (kinesthetic sense) is in support of my sense of hearing and makes my aural imagination that much quicker and clearer.

A very simple way for you to begin working on this skill is by playing lots and lots of simple melodies (again, highly familiar children’s songs are a good place to start) in all twelve keys. Every day. As you do so, don’t try to intellectualize the melodic movement (interval to interval), but instead, play by instinct and sensation. Just let your fingers (and/or breath, etc., depending on your instrument) follow your ears, and other senses.

Sing as much as you can as you learn new melodic/harmonic material, not only to deepen the clarity of your aural imagination, but also, to give your brain even more of a chance to experience the music through your senses.

The more open and free you are with your body, (as an Alexander Technique teacher, I work a lot with my students on this), the more information you’ll be able to experience through your senses. (Excess muscular tension can significantly interfere with your ability to sense and hear the music.)

So as you continue to grow your ear, please keep these three skills in mind. Make a decision to work everyday on improving and integrating them. The more you can transcend your intellect and connect with your muse, the more beautiful and expressive your music will be.