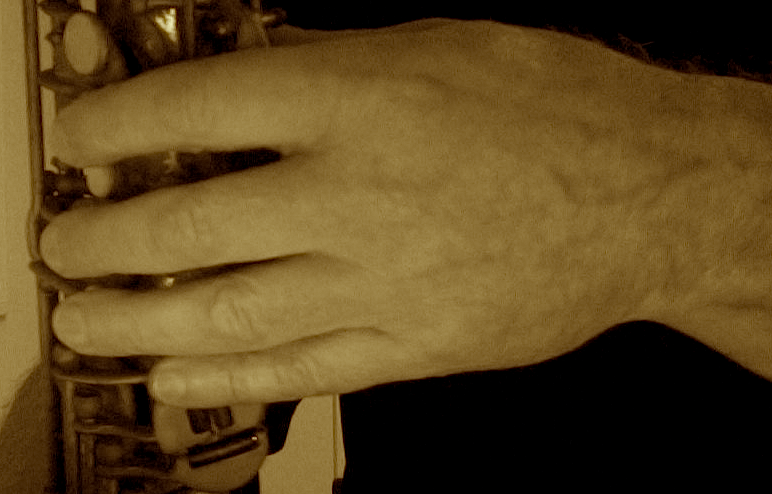

The sound you imagine and create on your instrument is the defining element of who you are as a musical artist.

I’ve yet to encounter a serious musician who doesn’t consciously dedicate a certain amount of time daily exclusively to the exploration and cultivation of their sound.

A beautiful sound is perhaps the essential skill for any musician. It’s your voice.

A very wise bit of advice I’ve often encountered goes something like this:

Make everything you practice a study in producing a good sound.

In other words, consciously play everything you play with your best possible sound. (The word “consciously” being key.)

I couldn’t agree with this more. (In fact, here’s a post I wrote about daily “sound meditation”.)

But I encounter far too many musicians who are not, on a daily basis, consciously cultivating what I consider to be the “other” essential skill in playing music:

Time.

Specifically, your sense of time and pulse as you play your instrument.

Your perception of time (and how you interpret that as a continuous “pulse”) is not only an immensely important musical component (some might say most important), but it is also foundational to your skill and coordination in playing your instrument (yes, even in producing your sound!)

And ultimately, your technique is only as good as your sense of time.

In my Alexander Technique teaching practice, I’m still taken aback by the percentage of musicians who come to me for help who don’t devote a specific amount of time in their daily practice toward the cultivation of their sense of time and pulse.

Many times, it is this lack of “vivid time imagination” (as I sometimes think of it) that is at the heart of the problems that brought them to see me in the first place.

Any coordinated effort (or intention) is dependent upon a sense of time in order for it to be carried out. (As I mentioned above, even how you produce your sound.)

And the foundation of a vivid musical imagination is time and rhythm. Whether you’re improvising or playing composed music, the more vividly you conceive of pulse and rhythm, the freer and deeper your musical expression will be.

To be clear, I’m not just speaking here of the importance of making sure you’re playing with a good sense of time whenever you’re practicing (or performing) whatever you’re practicing.

I’m speaking of setting side a certain amount of daily practice time with the specific intention of challenging and improving your sense of time. (A “time meditation”, if you will.)

So if you’re not already doing this, but would like to start, here are a few things to aim for and/or keep in mind:

- Address your specific needs-Take time to develop exercises for yourself that take you out of you comfort zone. What presents a challenge for you? Look for the things that give you trouble. But…

- Keep it simple-Use melodic patterns (for example, scale or arpeggio patterns) that are very familiar to you as you challenge your time skills. Don’t get distracted by the sequence of pitches.

- Work only with a metronome-Don’t use a drum loop or backing track. (See below for why I suggest this). Just the simple (but make sure it’s loud!) click of a metronome is the only tool you’ll need. (Drum loops and backing tracks are great practice tools, by the way, just not the best for our purposes here.)

- Aim toward minimum clicks-This is the essential tool for improvement. In order to develop an accurate sense of time and a lively sense of pulse, you need to develop your “temporal imagination” (as I call it). This means increasing the “notes-to-clicks” ratio with the metronome. I rarely get my metronome over 40 beats per minute when I’m working on my time. If I’m playing eighth notes in 4/4, for example, I’m going to have the metronome click only on the first beat (i.e., eight notes per click). As I progress the tempo upwards, eventually the eighth notes are “transformed” into sixteenth notes (i.e., sixteen notes per click), and so on. Always be listening for (aurally imagining) where the next click falls. (See below!) When you’re playing with a drum loop or backing track, it is the loop or track that is “feeding” you the time and feel, rather than having you imagine it.

- Imagination is key-What you should be working toward is “hearing” (aurally imagining) the rhythmic component of whatever you’re playing (continuous eighth notes, for example) as an even “pulse within a pulse” (i.e., your eighth notes as a pulse that lines up with the slower pulse of the metronome). The better you get at accurately anticipating the metronome clicks, you’ll find that you’re rhythmic pulse (i.e., the continuous eighth notes, in this case) becomes more uniform and even. (Really!)

- Work daily to address and challenge yourself with these three components time:

1. Perception of time (as stated above, how accurately and vividly you “imagine” time passing and how you feel “pulse”)

2. Rhythmic complexity (placing ever-increasing demands upon rhythmic combinations as you feel these combinations against the pulse of the click, including simple and complex polyrhythms).

3. Meter (increasing your capacity to conceive of and hear various metric subdivisions within a given metric frame , for example, learning how to “hear” 3/4 over 4/4; as well as displacing the click of the metronome to the other beats in the measure).

- Pay attention to your reaction-(This is me being the Alexander Technique teacher.) When you challenge your perception of time, it can be tempting to stiffen and compress your body. Make a conscious choice to check in with yourself frequently so that you’re not compressing your head onto your neck, or stiffening your shoulders, or locking your knees, etc. You’ll find that if you stay in a relatively fluid state of balance and mobility, your perception of time will noticeably improve.

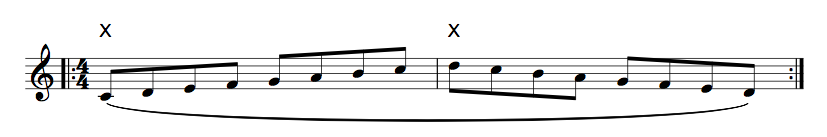

Here’s a simple exercise you can begin with to challenge your sense of time. (It’s also a useful way to discover where you are with your “temporal imagination). Take a simple major scale pattern in eighth notes and play it with the metronome clicking on beat one (the “X” above the first note signifies the metronome click:

Aim for playing this pattern as slowly as you can, completely legato. Start with the metronome set at 40 bpm, and begin by listening to the clicks for a while without playing. Practice imagining precisely and vividly where the click falls amongst the silence, then try to “hear” the space (the silence) between the clicks. Think of the metronome and your imagination working together to form a sort of “rhythmic drone”.

Next, imagine the sound of the pattern (again, without playing) as it lines up with the clicks. When you’re able to do this with a reasonable amount of consistency, pick up your instrument and play.

Start working your way downward on the metronome to at least 20 bpm, or slower. Listen to each note you’re playing as you repeat the pattern, as you also anticipate in your imagination where the “C” and the “D” line up with the click. Don’t go to a slower tempo until you can play it with considerable precision, consistency and confidence.

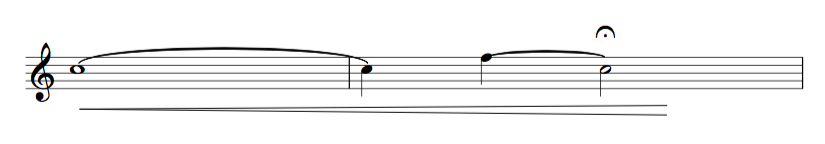

Once you’re confident you can do that at the slowest tempo possible, play the pattern I’ve presented below (sixteenth notes) at 40 bpm and work your way down to as slow a tempo as possible, aiming for evenness, vivid imagination of sound and pulse, and precise matching with the metronome click:

Don’t be discouraged if you can’t play the double-time pattern right from the start. Just stay with the eighth notes until you gain more skill and confidence. Keep things within your reach.

After you’re able to play these patterns accurately at as slow a tempo as possible, you can add a new challenge by playing the pattern with the metronome clicking on beat “2” (again, the “X” signifies the metronome click):

as well as:

And so on…

If you’d like to work more specifically in challenging your sense of time, meter and rhythmic imagination, I’ve made available for purchase two e-books:

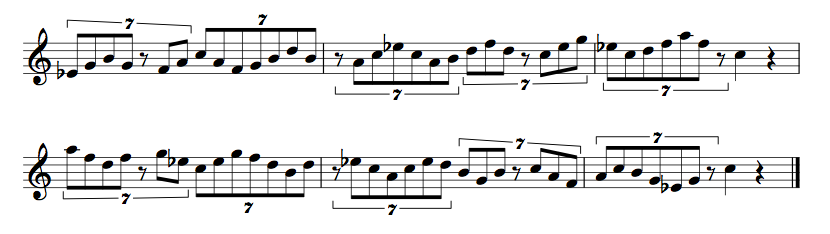

Rhythmic Dissonance: Exercises to Improve Time, Feel and Conception, is a methodical approach to challenging your perception of time, as well as expanding your ability with polyrhythms. It starts off easy and gradually gets very challenging. It’s like strength training for your “rhythmic muscles”.

Essential Polymeter Studies in 4/4 for the Improvising Musician, is a methodical approach to “hearing” and understanding the basic subdivisions of 3 (3/8 and 3/4), 5 (5/8 and 5/4) and 7 (7/8 and 7/4) against 4/4. If you’re an improvising musician, working from this book will liberate your improvisational concept and expression.

So here’s to encouraging you to find time in your daily practice routine to delve specifically into building your rhythmic skills. Exploring time and rhythm is a vast, interesting and edifying universe. Enjoy the journey!