Well timed and well directed rest is one of the most important elements for a serious musician to maintain and develop a healthy practice regimen. Unfortunately, many musicians neglect this crucial element, sometimes looking at rest as a necessary evil, something that steals precious time away from “real” practice.

But truth be told, it is rest in any activity that optimizes effort. All effort and no rest leads to fatigue, lack of inspiration, compromised technical habits, unclear thinking, and injury. I could write volumes on the when and how much of effective rest. Instead, I’ll introduce you to a highly effective way to practice resting that is taught and used regularly in the Alexander Technique. It’s called constructive rest (also referred to as active rest).

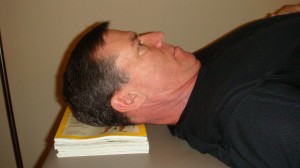

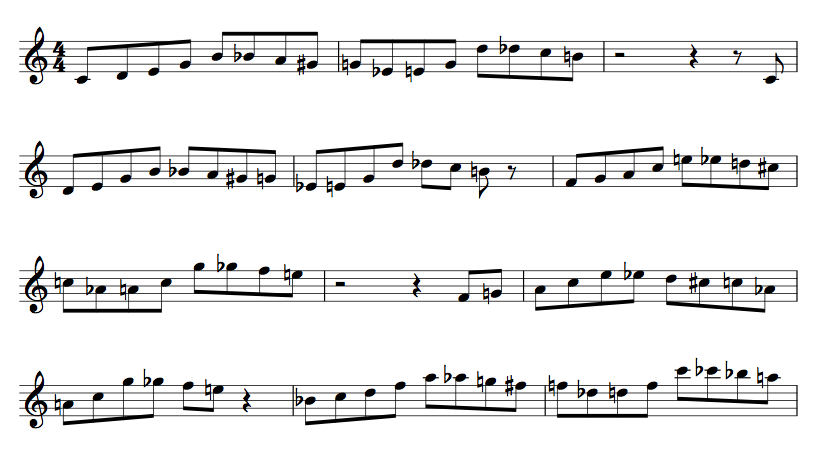

In this rest practice, you lie down in a semi-supine position (on your back with your knees bent and feet on the floor) on a firm surface (e.g., a carpeted floor) with something firm to support your head, such as books or magazines. Your arms are bent at the elbow with your hands resting on the side of your torso, somewhere between the bottom of your ribcage and your hips. You also leave your eyes open (remember it’s called active rest) so you can keep your senses in tune with your body. It looks like this:

Simply lying in this position for 15 to 20 minutes at a time can work wonders for you. Here are just a few of the benefits of constructive rest:

- It helps to restore the length of your spine by letting your back and neck muscles release into their natural resting length.

- It allows for your intervertebral discs (the soft cushions between your neck and back bones which absorb shock) to re-hydrate to their optimum thickness (this too lets your spine get back to its resting length).

- It allows your breathing to return to an easy, natural and well-functioning state.

- It calms your nervous system, clears and centers your mind and brings you back in touch with the present moment.

- It helps you to become better aware of your habits of tension (and helps you connect thought to gesture to reduce your tension) thereby giving you a better gauge of effort and tension when you play music.

- It puts you into a state of calm alertness, readying you to play music at your highest level.I’ve been practicing constructive rest for many years now, with ever increasing benefit.

For me it’s as essential as sleep, food and hydration to stay healthy and play my best. If you have chronic back and/or neck pain, this procedure can greatly reduce or even eliminate your symptoms. Here are the basic instructions for lying down in the semi-supine position for constructive rest:

Find a reasonably quiet place. If possible, allow yourself fifteen or twenty minutes to lie down.

Lie with your backside down on a flat, firm surface, e.g., a carpeted floor, or a wooden floor with a yoga mat or thin blanket beneath you. Do not lie down on a bed, cot, or sofa, as these surfaces are too soft and will not allow for the necessary feedback your body needs to release muscles.

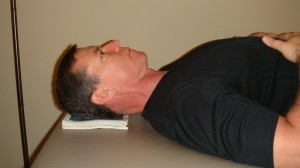

You should also place something firm beneath your head for support, such as a few thin books or magazines. The height of this support will vary with each individual. If too high, the chin will be too close to the chest and will not allow enough space in the front of the neck; if too low, the head will tend to go “back and down” the spine, thus discouraging the natural lengthening process. Try different heights and find one that encourages the least amount of tension in the entire neck:

Too high

Too low

Good height

Once you are on your back, bend your knees to bring your feet flat onto the floor. Keep your heels in approximate line with your sitting bones. Your heels should be about twelve to fifteen inches from your buttocks.

Keeping your arms out and away from your torso (think of your arms as hands of a clock at 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock), bend your elbows to bring your palms to rest on the sides of your torso where your ribcage meets your abdomen. Make sure your hands are not touching one another, and that there is plenty of space between your ribcage and elbows:

Shoulders narrowing (arms too high)

Shoulders widening (better arm position)

Check your breathing by observing the flow of air in and out of your nostrils. Keep your eyes open during the entire session, from time to time noticing your environment. Scan yourself for any unnecessary tension or holding that you might be doing. Observe any changes within yourself that might take place. Rest and enjoy!

That’s all there is to it. By simply lying in this manner you activate great release and positive changes. If you like, you can also add the Alexander Technique primary directions. This is a simple set of mental directives to give yourself to encourage length and expansion in your body. They are as follows:

I allow my neck to be free, so that my head can release upward off the top of my spine.

I allow my entire torso to lengthen and widen.

I allow my knees to release forward from hip joints, and for one knee to release away from the other.

I allow my heels to release into the floor.

You simply think the directions, but don’t do anything about them. In fact your entire aim should be to do nothing at all. Non-doing we call it in the Alexander Technique. Just let yourself rest.

You can use this tool anytime you like. In my musical practice, I tend to use it as follows: I usually lie down for about 5 or 10 minutes before I practice to help bring me to the state of calm alertness I need to play well. When I take brief breaks during my practice (5 to 10 minutes) I’ll also lie down.

Or sometimes I’ll take a nice long break in my practice session and lie down for an entire 20 minutes. When I do this I feel completely restored (mind, body, spirit) and ready to resume. I often do this when I have an unusually long practice day.

Also, if I’m at a gig where space permits, I’ll lie down before I start and during the intermission (or sets). I’ve been told that in the U.K. (where the Alexander Technique is widely known and practiced by professional musicians) you can see 40 or more musicians lying down back stage during the intermission at orchestral performances.

So incorporate this highly effective tool into your practice routine. If you can’t manage 15 or 20 minutes, do it for 5 or 10. It will still help. Remember, rest is part of the process to improve, so don’t look at it as time wasted. Balance rest with effort and you’ll greatly increase your chances of staying healthy, injury free and energized as you practice and perform.