Being able to read music well at sight is a skill that just about any musician in any genre should aspire to. The really good sight readers I’ve played with not only play the music reasonably accurately at first sight, but also, they tend to be able to really make music out of it, really make the notes jump of the page.

In my work as primarily an improvising saxophonist, I wouldn’t say I devote the attention (both in work and practice) to sight reading that say, a pit orchestra musician might. But I do work on keeping my reading skills in decent condition. Even in my musical world it makes playing with others nicer for me and for them. I waste less time struggling with the notes, plus I’m able to find music in the notes more readily. Win/win situation.

So at the request of some of my students, I thought I’d offer some suggestions about improving your sight reading. Some of these suggestions are things that you need to practice, and others are things you can do immediately to improve your reading.

All this assumes you already have a good grasp of music reading fundamentals. If you don’t, take a class, find a book, find a teacher or get a friend to help you get started on you journey to becoming literate in the notated language of music.

IN THE PRACTICE ROOM

It probably comes as no surprise that those who read well spend a good deal of time reading. It’s as simple as that. So here are some suggestions about what you can practice to improve:

- Become a master of time-Work with your metronome on very slow, easy pieces. Learn to really listen and feel the time. Wait for the time; don’t anticipate. Pay attention to yourself primarily, keeping your own ease, breathing and balance in mind as you do so. You cultivate great habits of reading in performance by doing so.

- Become a master of rhythm-Keeping the rhythmic flow going as you read is of top importance. The best sight readers I know will sometimes play the wrong pitch, but rarely ever play the wrong rhythm. And if they do, they keep the whole thing flowing along, never being put off track by their mistakes. This rhythmic flow not only keeps the “illusion” of accurate sight reading, but also, it keeps you engaged in hearing and responding to the music in the most helpful way. Two very good basic books for improving your reading of rhythms are, Modern Reading Text In 4/4 Time, by Louis Bellson, and, Rhythm Reading, by Daniel Kazez. Working with, and understanding, polyrhythm and polymeter can also significantly improve your sight reading ability. (I have an eBook available that methodically introduces and explores polymeter, entitled Essential Polymeter Studies in 4/4.)

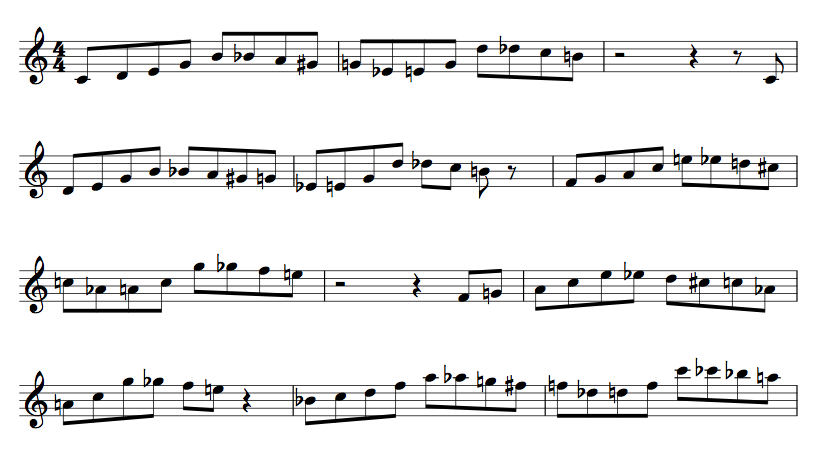

- Construct and practice from your own sight reading book-Put together a huge book, maybe an inch or two thick of things to sight read. Find pieces that run the range from exceedingly simple and easy, to more challenging, all the way to somewhat beyond your comfort zone (or even your ability), and organize them from easy to difficult. Make a commitment to play something from the book every day. Try to find pieces that are short, so even if you don’t have much time you can still play several pieces in various keys, time signatures, styles, etc. The internet is loaded with great resources for free, downloadable music in a multitude of genres.

- Practice paying attention to the details-Find pieces that are fairly easy to play rhythmically pitch-wise, but have loads of articulation, dynamic and form challenges (complicated road maps). Aim toward seeing and paying attention to these details with the same sense of priority you give to pitch and rhythm. Learn to cultivate the ability to see all the detail of the music at once.

- Sing-Practicing sight singing is a great way to improve your instrumental music reading. It gets you to really absorb the material on the page and immediately turn it into meaningful sound. Not only will this help you with your pitch-reading accuracy, but also, it helps you sound confident and musical as you read.

- Practice music that is not for your instrument-This is a great way to challenge your reading at less than ideal ends of your range and to address technically “awkward” movements on your instrument. I’ve seen some pretty decent readers fall apart the moment the piece starts spitting out a bunch of notes in the extreme range of their instrument. It’s not like they can’t play it. It’s just that they sort of “give up” trying to stay with this ocean of perceived “difficult” notes. Don’t let that stuff throw you off your game.

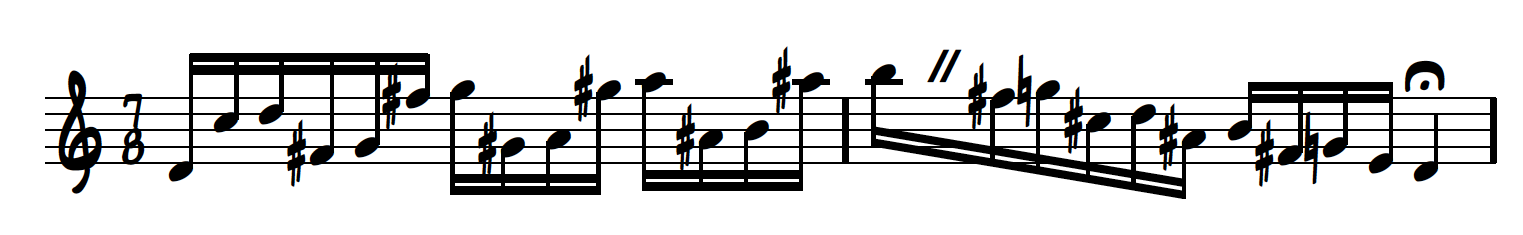

- Transpose-If you play a transposing instrument, like saxophone, you have to be able transpose some things at sight. And even if you don’t it’s a great way to get your brain taking in and processing the information on the page at light speed. Do this everyday and discover how easy it is to read flurries of sixteenth notes that you don’t have to transpose. It works.

WHAT YOU CAN DO IMMEDIATELY TO IMPROVE

Whether in the practice room, playing a gig, or sitting in at a rehearsal, here are some ways to help you work optimally:

- Pay attention to yourself-Really. Always aim to play with ease and balance, and as you read music, don’t let yourself be pulled away from that ease and balance. In particular, avoid tensing your neck, shoulders and back, and make sure that your breath is flowing readily. This will help you to maintain a state of psycho-physical well-being which keeps you in the best condition to deal with the unknown (the music!)

- Scan the music before you play-Make it a habit of looking carefully (as time permits) at the music before you play it. Notice the fundamentals first: key signature and time signature (and if they change!), repeats, road maps (D.C., Codas, etc.), dynamics, etc. Then see if you can notice any potentially tricky passages and give yourself a few seconds just to take the information in. You’ll be pleasantly surprised at how this transforms your confidence and execution when the group starts actually playing the piece.

- React differently to your mistakes-When you do make the inevitable mistakes, try not to lose your good balance (see above). Remember to be easy with yourself, let your neck, shoulders and back stay free, as well as your breath. By not flinching every time you make a mistake, you allow yourself to keep the musical flow. Very important. This is also something you can begin to apply in the practice room. When you learn to let your mistakes go, you play better.

- Trust your judgement-Don’t assume that the player next to you is right and you’re wrong when you enter at different times in the piece, or otherwise seem like your not in sync. This is where some fairly decent readers sort of fall apart. Their confidence is turned inside out. Remain close to your reasoning and discernment, and don’t be afraid to be right.

- Stay in touch with your sound and pitch-Often you can tell when somebody is reading simply because their sound becomes strange and tentative. Allow your sound flow out with confidence and self expression. Let those wrong notes be supported by a beautiful tone and good intonation. You’ll be amazed at the difference that makes in how you sound.

So there you have it. A few of the key things I put in practice to make me a better sight reader. I think they can help you, too.