In the study of jazz (as well as many other improvisational music disciplines) transcription of improvised solos is standard practice. Jazz is often described as being a “language”, and one of the best ways to learn this language is through listening and transcribing.

There are various skills you develop from transcribing solos.

Many teachers of improvisation have their students transcribe solos to learn this so-called jazz language, as well as to give them a chance to build a vocabulary of useful “licks” that can be practiced in all 12 keys and applied to chord changes, tunes, etc.

Transcribing is also a great way to improve technique, as you most likely will be confronted with sequences of notes that just don’t fit easily into what you’re used to playing. And of course it’s a great lesson in jazz harmony as you analyze what the soloist has played.

But I think the most valuable skill you gain when you transcribe a solo (and the number one reason why you should consider doing it) is that you learn how to listen in a deep way.

Deep listening. You see, when you transcribe an improvised solo, you’re listening to more than just the pitches being played. You’re listening to tone color, attack, dynamics, articulation, tempo/rhythmic play and more, as it unfolds in the real time environment of the recording.

But you’re not just addressing the musical elements separately, as I’ve listed above. You’re also going deep into the mind of the artist. It’s almost as if you’re attempting to embody his/her experience in creating the solo. You’re learning to hear and reproduce sounds that musical notation could never fully or accurately express. You’re learning to actually understand and speak the language.

Each note has meaning. Each inflection has weight. Every element the improviser has chosen is related to every other element. And all this is happening as a whole experience of communication and response between the soloist and the rest of the ensemble. And you’re right in the middle of that experience.

Of course you vastly improve your ear for discerning pitch and rhythm. The more you transcribe, the easier it becomes. This is true largely because you are able to hear, understand and retain more in your working memory. And that translates into huge gains in your own playing. You go from a more self-concious, intellectual approach to improvising, to one in which you trust your muse and follow your ears.

When you transcribe, you’re developing the ability to listen at a high level of consciousness, learning to pay great attention to detail, and cultivating your musical imagination.

This is why many teachers of jazz improvisation recommend that you study only solos that you’ve transcribed, and not from the written notation of somebody else’s transcription.

The great jazz pianist and teacher, Lennie Tristano, would have his students (Warne Marsh, Lee Konitz, et. al.) devote themselves to listening to a solo for a long period of time (often several weeks) before he’d have them transcribe it. He’d insist that they be able to sing it absolutely accurately: pitches, rhythms, scoops and bends, articulations, dynamics…the entire feeling of the solo. His main objective: to get his students to listen deeply.

I think it’s fine to play other people’s transcriptions, by the way, but with different objectives in mind. For me personally, they’re a great way to improve sight reading and technique, as well as sometimes a chance for me to get immediately more familiar with an artist that I might not have much experience with. Plus, it’s just plain fun.

But if I want to go deep, I have to do the transcribing myself. And I encourage you to do so, too. The benefits are just too huge to ignore.

If you’ve never transcribed a solo before, here are some things to do/keep in mind to help you out:

- Choose a solo that you really love-As obvious as this sounds, you might be surprised at the amount of novice transcribers who are slogging away in their first transcription attempt at a solo that they think they should transcribe (perhaps for its historical or musical significance), as opposed to what they really want to transcribe. If you’re compelled by the material, that motivation will take you far, and you’ll enjoy the process much more. But….(see below)

- Keep it simple-Choose something that is easily singable, not too rhythmically complex. Find something lyrical and spacious. Lots of flowing eight notes punctuated with quarter notes and rests.

- Listen, listen, listen-For a long time. If you can sing the solo accurately (the way Mr. Tristano had his students do), you’ll be amazed at how fast and easily you can find the notes on your instrument. Also, I recommend your first few transcriptions be limited to the artists who play your instrument. So if you play alto saxophone, for example, transcribing Paul Desmond would be highly user friendly, a good place to start (as long as you like Paul Desmond).

- A little bit at a time is fine-If you’re intimidated by the length of a solo you really like, remember that you don’t have to transcribe it all. See if you can get the first phrase. Then the next. Work your way up to transcribing a chorus. If you feel it, continue on. Make it a long term project and enjoy the sense of accomplishment as you make it to the end. If you don’t make it to the end, that’s fine too. You still will have learned a good deal, and will have improved your skills. No regrets.

- Slow it down-If it’s just going by too fast for you to take in, consider some of the software and smartphone apps that are designed specifically for transcription (to slow the tempo of a recording without altering pitch). One well-know software application is Transcribe!, by Seventh String. And of course there are lots of smartphone apps available now that do the trick.

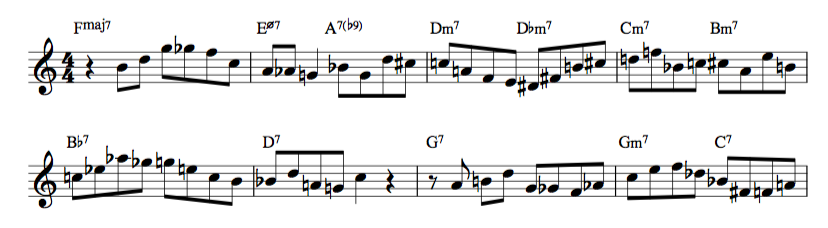

- Don’t write anything down-Not at first anyhow, as it can be a sometimes frustrating distraction. It’s important that the solo goes deep inside of you. That you know every note and every inflection, and that you can play it back to your satisfaction by memory. Once you can do that, feel free to write it out. It’s a great skill to develop as well (particularly for helping you read and understand rhythms).

Above all, enjoy yourself. By learning to listen deeply and reproduce sounds and rhythms in such a specific way, you’ll broaden your musical expression, become clearer as to who you are as an artist, and teach yourself to trust your ears. Best wishes!