The word “no” often gets a bad rap, especially in the realm of self-improvement. Saying “yes” opens and expands the possibilities goes the conventional wisdom, whereas saying “no” closes or limits them.

I’d say that’s mostly true.

Except sometimes saying saying “no” opens up unexpectedly wonderful possibilities.

As a teacher of the Alexander Technique (and as a musician who applies the Technique to my practice and performance) the ability to effectively say “no” is the most powerful tool I know of to make profound and lasting changes.

How could that be?

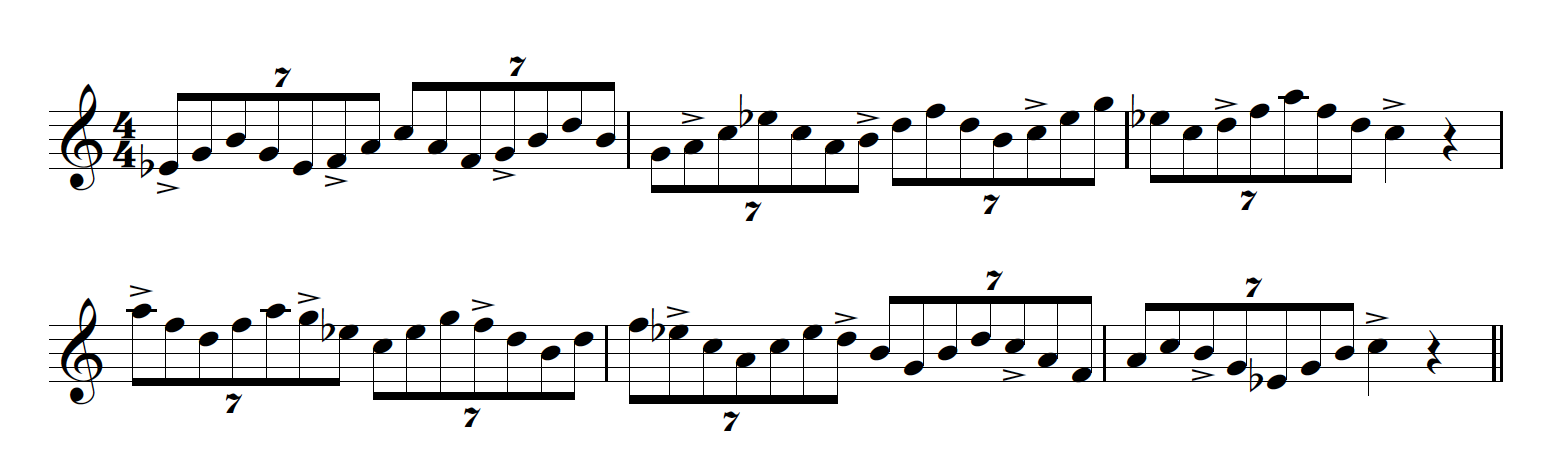

Let’s start with what it is I’m saying “no” to. With saxophone in hand, the moment I think about playing a single note, my brain readies me for the task. It does so by “pre-firing” the muscles involved in playing the saxophone. I’ll call that my habitual response. (And yes, we do need habit to play music or to do just about anything else, for that matter.)

In the past my habitual response would be to tighten my neck, pull down into myself, stiffen my shoulders and suck air in noisily to inhale. I would also narrow my focus and shift my attitude into an almost warrior-like fashion, cutting myself of completely from anything except the thought of playing.

Much of that “pre-fired” pattern of muscular response was not only unnecessary to playing my instrument, but also, inefficient and harmful.

What also came along with this habitual response was trouble. Besides the neck, shoulder and back pain I was getting, I was also developing some serious coordination issues that threatened my playing career.

Then I discovered the Alexander Technique. I immediately realized that for me to change these now debilitating habits, I had to learn to effectively say “no” to my habitual response to playing the saxophone. To make a very long story short, I have learned, and my playing has not only dramatically improved, but I continue to be edified and continue to cultivate my artistic expression by going deeper into the power of no.

You see, when you say “no” to your habit, you say “yes” to the possibility that something different will happen. You actually expand the possibilities.

When I learned to say “no” to all the tension and struggle I was bringing upon myself, I became free to play more in accordance with my imagination and intentions (and I continue to cultivate this freedom).

I teach classes in the Alexander Technique at the American Musical and Dramatic Academy in Los Angeles (part of a BFA and conservatory program for singers, actors and dancers). In one of the first class sessions, I have the students explore the power of no by playing a simple children’s game, called Simon Says.

As you probably know, Simon Says is a game in which “Simon” (in this case, me) gives various commands that you must carry out (like raising a hand, for example). But you can only carry out Simon’s command if he precedes it by saying “Simon Says”. If you carry out the command without Simon saying “Simon Says” you lose.

I’ve become very good at being Simon, and can usually stump an entire class of 12 students in no time. Then we talk about why the lost and we begin again. After playing two or three more times, I can’t stump anybody. They’ve all mastered the winning principle of the game.

And this winning principle is to stay in a constant state of saying “no” to oneself until the time is right, until Simon says. (In Alexander Technique jargon, we call this conscious state of “no” inhibition.)

The most interesting thing to me as I play this game is how the students appear differently from start to finish. In the first round, their eyes are focused and narrow. Their shoulders and necks are tense. Lots of breath holding, too. They’re all in what I call a “hyper-reactive” frame of mind.

By the time we get to the third round (mind you, I stop between each round and give them some guidance) they look completely different. Soft faces, calm eyes, easy breathing, freer necks and shoulders. They look poised.

I tell them, “Now you are in a state of true readiness. You’re calm but alert. This is a great state to be in when you perform.” For many of them that’s a revelation. Performance mode has always been a hectic, tense scramble. Now it is anything but.

I usually have one or two of them perform right after this. The results are often stunningly different. Easy, powerful, authentic performances. This becomes the door that we use to explore performance for the rest of the semester. Saying “no” begins to have a powerfully positive meaning to these students.

As a jazz artist, I can usually hear (and see, if it’s a live performance) when an improviser is in this “no” state of mind. Certainly Miles Davis was in this state most of the time when he played, as was Lester Young.

To be clear, it’s not a dead and passive state of mind. It is an active state of mind that allows you to say “yes” to good things that might happen. Yes to joyful surprise. And that’s good for both artist and listener.

I’d say that when I’m in finding good flow as I’m playing (when I’m in the zone) that I’m in a perpetual state of no. It’s as if I’m waiting patiently for the music to come through me. It’s a beautiful thing.

So notice how you react as you go to play your instrument. Do you prepare to play that first note by tensing up and narrowing your focus? What happens to your shoulders and neck? Do you stiffen your legs? Your arms? Does your attention narrow or expand? What happens to your breathing?

If you find that your starting with too much tension, practice saying “no” to yourself as you begin again. See if you can reduce that tense response even a little bit. If you’re persistent in this endeavor, you’ll be delighted in how you can improve.