Performance anxiety, whether mild or debilitating, is nearly a universal human condition. It is not only musicians who struggle with it. Anybody who has had to “deliver the goods”, on the spot, in real time, has probably experienced some anxiety. Performing artists, athletes, as well as business people, educators, (and just about anyone else) have all probably felt anxious before an important performance, presentation, or public appearance.

Many musicians are reluctant to admit to having performance anxiety. They see it as some form of weakness, or character flaw. I’m here to tell you that there is no shame in being anxious about a performance.

There might be a variety of reasons why you become anxious before a performance, but that all have one thing in common: your love for music. You want to put out the best musical expression you can. In short, you get anxious because you care. If you didn’t care you wouldn’t become anxious.

You probably wouldn’t perform that well, either. Because if you don’t care, you won’t play well. You must care. So if you do care, but have problems with performance anxiety, read on.

In the language of the Alexander Technique, performance anxiety occurs because of “end-gaining”. When end-gaining, you take yourself out of the present moment, and bounce back and forth between regretting what you’ve already played, and dreading the unknown outcome of what you will be playing. You stop paying attention to process, and place too much of your attention on expectations and results.

It’s important to realize that a musical performance, like all other human activity, is a step into the unknown. And the best way to step into the unknown is to remain in the present moment, always paying attention not only to what you’re doing, but also, to how you’re doing it.

You can’t control the unknown, but you can control to a large degree your reaction to the unknown. The first thing to do is to accept whatever feelings you have in the moment, whether it’s fear, worry, enthusiasm, anger, or anything else that might arise in you. That way you can observe the changes in your body as you react to those feelings.

Performance anxiety, which triggers a fear response, manifests itself as a series of challenges or obstacles that interfere with your ability to perform to your fullest potential. Some of these are:

- Shallow and uncontrollable breathing

- Overly tense muscles

- Loss of balance

- Unclear thinking

- Dry mouth

- Moist hands

- Impaired sense of time

- Trembling

The list could go on, I’m sure.

From a practical point of view, a primary interference in your ability to perform well is excess muscular tension. If you’re causing your muscles to become unduly tense and rigidly over-reactive, you seriously impair your ability to create the necessary movements to play music.

And when I say movement, I mean all movement, including the movements involved in breathing. If you’re interfering with your breathing, you face even more problems. (If you play a wind instrument or sing, I don’t have to tell you why that’s a problem.)

But even if you don’t play a wind instrument or sing, there is another equally serious problem that arises when your breathing is uncontrolled and shallow: Your thinking becomes unclear. When this happens, you forget important details of the music, lose touch with time and pitch, and make mistakes that you never made during practice. We’ve all been there before.

If you’re going to reach your potential as a performer, you must learn to prevent some of this excess muscular tension.

So what causes these symptoms of performance anxiety to arise in you? The answer is simple: your thinking does. If the thought of performing causes fear, a whole host of changes will take place in your body.

The good new is that you can also use your thinking to prevent (or at least attenuate) these conditions that arise in you that are counterproductive to performing at your best.

I’d like to offer some ways you can redirect your thinking to help you better prevent the negative manifestations of the fear reaction that accompanies performance anxiety.

I’m not telling you how to stop being afraid. Rather, I’m giving practical advice that will help you perform better, even when you are afraid and anxious. Though this might seem like a lot to think about, remember that most of these things can be thought of in an instant, and in that instant you can make a huge difference in how you perform.

Before the Performance:

Acknowledge your fear (as opposed to denying it), and notice how it specifically manifests itself in you physically. How is your breathing? Where are you tightening up in your body? This will give you an idea of what specific responses you wish to prevent.

Again, you might not be able to prevent the feeling of fear, but you can gain control over many of the tense response patterns you make because you are afraid. That in of itself will significantly improve how you play. As a bonus, when you consciously reduce your tension in this way, you gain an immediate kind of confidence that helps you regain your clear thinking.

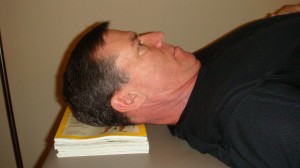

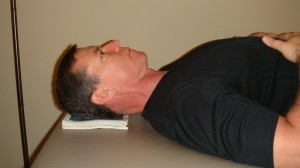

If you have a chance before the performance, calm yourself by being relatively still and restful. Let yourself stay present with this stillness and restfulness. This is a great time for constructive rest. Also, some breath work (such as whispered “ahs”) is helpful not only to control your breathing by lengthening your exhalation, but to calm your nervous system as well.

At the Start of the Performance

Before you actually play that first note:

- Bring your attention to your breath by noticing the air moving in and out of your nostrils, and see that your breathing is quiet (no gasping or sniffing).

- Bring your attention to your head, neck, shoulders and back , noticing (and releasing) any excess tension

- Check that your knees are not locked, and that your legs are not overly tense. Think of your knees as releasing away from your hip joints, and away one from the other. In other words, let your knees soften.

- If you are standing, bring attention to your feet, letting your weight go completely through them so that you can release up and stay in balance. Think about your heels as releasing down into the floor, and let your toes spread out onto the floor. (Don’t curl your toes.)

- If you are sitting, let your weight go through your sitting bones, letting your feet rest easily on the floor. Again, don’t curl your toes.

- Let your arms and hands soften, releasing any unnecessary tension. You can think of your shoulders as releasing away one from the other.

- Shift your emphasis from trying to play well, to using yourself well while you play, breathing and moving easily. Remind yourself to take your time.

As you perform, and as time and circumstances permit, refresh some of the above thoughts. The most important are:

- Awareness of breath (allow it to move in and out quietly)

- Head, neck and back, releasing unnecessary tension

- Softening your knees.

- Letting your heels release your feet into the floor

- Letting your arms and hands soften

- Return back to your breathing

This is something that needs to be practiced. After all, I’m asking you to pay attention to yourself primarily, as you perform music (not so easy at first). The great educational philosopher, John Dewey, called this “thinking in activity”, and it is what the Alexander Technique is specifically aiming for. You are developing a highly valuable skill.

I can assure you from my own experience, that when you learn to pay attention to yourself in this way as you play music, you will play better. You are the primary instrument. You make the music. Keep that in mind.

If you take advantage of each performance as a chance to practice some of these things, and develop this skill, you’ll greatly improve your ability to manage your anxiety (and will greatly improve the quality of your performance).

Check with yourself, asking a basic question: “Am I enjoying this or am I afraid of something?” Pay attention to your reaction to this question, and see if you can notice how your reaction might interfere with your ability to perform well. Be patient, evaluate yourself with kind discernment, and allow yourself to grow and explore.