The vast majority of jazz pedagogy materials (books, DVDs, etudes, etc.) place great emphasis on tonality. This is true for beginner through advanced artist level.

The vast majority of jazz pedagogy materials (books, DVDs, etudes, etc.) place great emphasis on tonality. This is true for beginner through advanced artist level.

If you’re a serious student of improvisation (at any level of proficiency) it is, of course, important to be continuously finding new ways to organize tonality: harmonic extensions/substitutions, auxiliary scales, intervallic patterns, effective voice leading, etc. It is by exploring these materials that you can find seemingly endless ways to create tension and resolution in your improvised lines.

Yet, no matter how much you’re adding to your tonal palette, you’re improvisations are still being driven by one main force: rhythm.

That’s right. As far as your brain is concerned, rhythm is primary.

It is the impulse to move the pitches that brings your improvisations to life. This sub-verbal “movement impulse” is more immediate from your brain to your muscles than the thought (whether aural or intellectual) of how the pitches are organized.

Of course, in a beautifully expressive and fluently improvised solo, there is a seemless connection between the rhythmic impulse and note choices. It may be for this reason that lots of jazz improvisers don’t devote much time specifically developing their rhythmic imaginations.

For some, this leads to a rather hardened, predictable phraseology. Because so many standard songs and classic jazz compositions are composed in 4/4, and are constructed largely of two-bar and four-bar cells, it can be a strong (almost irresistible!) invitation to improvise melodic lines that emphasize the song form at the expense of melodic freedom.

Yet it is precisely this freer phraseology that is at the essence of modern jazz improvisation. If you go back to the great tenor saxophonist Lester Young, you can hear/experience a beautiful “floating” kind of time feel and rhythmic expression that seems to simultaneously embrace, yet transcend, the form of the composition.

In the simplest sense, Lester Young wasn’t “trapped” by the bar lines. Each phrase had meaning, freedom, and a highly unpredictable spontaneity.

If you listen to some of the earliest recordings, you’ll hear him “turn the time around” fairly regularly throughout his solos. It was that rhythmic freedom that served as one of the foundations of the bebop/modern jazz aesthetic.

Yet as time went by, and harmonic possibilities in modern jazz became more plentiful and complex, rhythmic exploration sometimes took a back seat.

It is for this reason that I decided to write and compose my ebook, Essential Polymeter Studies in 4/4 for the Improvising Musician.

Some years back, after spending huge amounts of practice time increasing my tonal (harmonic/melodic) vocabulary, I realized I was stuck in my phraseology. As I recorded myself practicing (and after listening to several of my recorded performances) I noticed an unwanted predictability in my phrasing.

I soon realized that much of this predictability had to do with meter. Specifically, if I were improvising in 4/4, all the phrases fit a lttle too neatly into that subdivision.

I began exploring with superimposing other metric subdivisions over 4/4. I started with learning to imagine and feel 3/4 over 4/4. After just a few weeks of exploration, my improvising began to really open up.

Not only was I playing freer, more spontaneous sounding and less predictable phrases, but also, the way I organized the pitches began to open up. I began to find surprise and delight in my improvisations.

I was hooked. After 3/4 over 4/4, I began to explore 5/4 over 4/4. To make a very long story short, I went on to explore other subdivisions, all with wonderful results.

I’ve turned my explorations into a methodical approach to understanding, hearing and imagining polymeter as it applies to improvisation. Because the topic can be so vast, my challenge was to limit the field of study to the most essential subdivisions and rhythmic patterns. I think I’ve been able to do that.

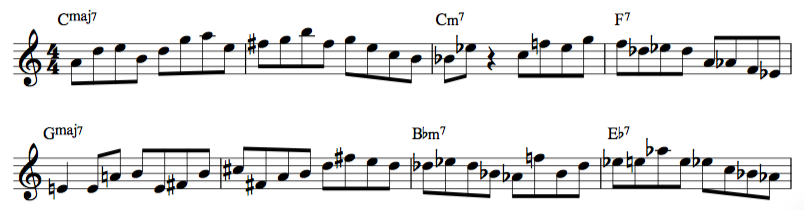

In Essential Polymeter Studies in 4/4, I’ve presented nearly 160 pages of notated exercises. Most of the exercises are common rhythmic patterns constructed from the staples of modern jazz tonality (dominant 7th scales, major, melodic minor, diminished, blues, augmented scales, etc.)

Each pattern “moves around” (displaced) the bar line to challenge you to always know where beat one is, and to help you develop an unconscious ability to sense how odd-metered patterns “return” when played over even meter.

Of all the jazz etude books I’ve composed so far, this is the one I’ve put the most time, thought and effort into. I believe there is nothing quite like it available for the serious student of jazz improvisation, and am very happy to have made it available.

So if you’d like to find new ways to expand your improvisational language, please consider my book. And let me know what you think. (On the landing page you’ll find a downloadable sample from the book). Thanks!