One of the things that too often goes hand in hand with playing at fast tempos is excessive bodily tension. This is not a requirement of the music. Instead, it’s largely because of the habits, perceptions and attitudes of the performer. It doesn’t have to be like that.

One of the aims of the Alexander Technique is to learn to approach any activity with a minimal amount of misdirected effort. Ease, efficiency of movement, freedom, clarity, balance.

As an Alexander teacher and practice coach, I help my students become aware of and prevent the various movement and postural habits that interfere with this easier, more efficient way of playing music. This is mostly a matter of getting them to change how they pay attention as they are playing.

Many of the problems of excess muscular tension musicians have begin with their thinking. Playing at fast tempos is a prime example.

One of the things that invites all this unwanted tension is something I call “micro-managing” the pulse. In essence, this means that you conceive the tempo as fast beats coming one after the other.

For example, in 4/4 time, at a tempo of quarter note = 262, the quarter note pulse moves by quite rapidly. If you try to feel each beat this way, it not only invites excess bodily tension (you might try to tap your foot like mad as you tighten the rest of your body), but also, it creates a feeling of urgency that scrambles your thinking a bit. It makes you less open to the control and choices available to you.

If you watch some of the great jazz masters playing at these fast tempos, you virtually never see them moving with the quarter note pulse this way. Why? Because they conceive of the pulse in a broader sense.

This means that instead of trying to feel 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4, etc. as the main pulse, they tend to feel it more as a broad 1…1…1…, etc. (each “1” being the beginning of the bar). Some feel it even more broadly than that, feeling the time as long phrases crossing bar lines.

This shift in time perception tends to do two helpful things for these masters:

- It helps them to maintain a helpful level of physical and cognitive ease, flexibility, responsiveness and balance that supports a great technique (sound, too!)

- It helps them imagine and create the music in an entirely different way, with many more rhythmic and phrasing possibilities as well as note choices. Instead of merely “making the tempo”, they’re actually expressing themselves with a great deal of clarity and choice.

So no matter what kind of music you play, you’ll play with less misdirected effort and more precision if you broaden your perception of the tempo. Here are some guidelines you can use to help you with this:

- Stop relying so strongly upon your foot. Seriously. Learn to feel the time without doing that. If you watch great classical musicians playing at blistering tempos you don’t see that foot flapping around. Same with many of the jazz greats. It’s fine to move with the music. But think of it as a lilting dance instead of a foot-stomping-neck-tightening lurch.

- Start reducing the metronome click. Once you’ve got the basic idea of the piece under your fingers (or the harmonic form, if you’re a jazz player) stop setting the metronome on the quarter note. At the very least, set it to half notes, with the aim in mind of letting it click once at the beginning of each measure. So, for example, quarter note=260 becomes half note = 130, which then becomes whole note = 65. I rarely let my metronome go faster than about 80 bpm (that would be feeling the pulse on the first beat of each measure at quarter note = 320!)

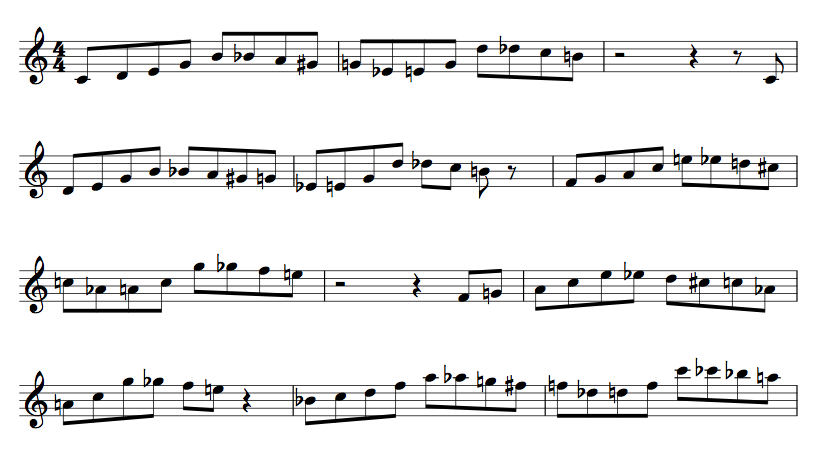

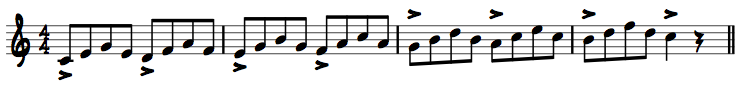

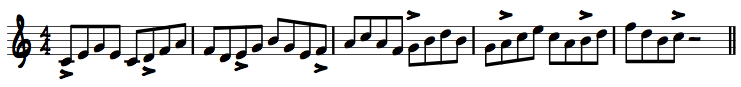

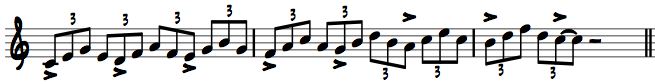

- Think more broadly about rhythmic groupings. If you’re working on a fast eighth-note passage, for example, start thinking of this passage as slower sixteenth notes. Or even slower 32nd notes (yes, really!) Use your metronome.

- Go from even to odd. If you’re working on a very symmetrical phrase, pattern, exercise, etc., consider modulating it metrically. This change in perception can really free you from your habitually tense anticipation of playing it. So, for example, if you’re working on a phrase that is grouped as sixteenth notes, try playing that same phrase thinking of the notes as triplets, or even quintuplets (maintaining the same velocity of each note). Again, use the metronome for this.

- Practice rhythmic displacement. This is another way to help you to think outside the box about tempo and rhythm. It has a similar benefit as the “even to odd”, I’ve mentioned above. Here’s an article on how to approach this.

- Reconsider beats “2” and “4” (for jazz playing). I know it is standard for many students of jazz to set the metronome to click on beats 2 and 4 (in 4/4 time) in order to help them feel the backbeat. But once you’ve reached a place in your musical development where you’re swinging comfortably, consider setting the metronome to click only on the first beat of each measure (especially at faster tempos). Besides helping you to stay less tense, this will also significantly improve your sense of time (it can be a bit of a challenge at first).

So whether you’re playing jazz, working on an etude, or even sight reading, thinking of the beat in this broader way will help you to stay calm and free. Give it a try and let me know how it goes.