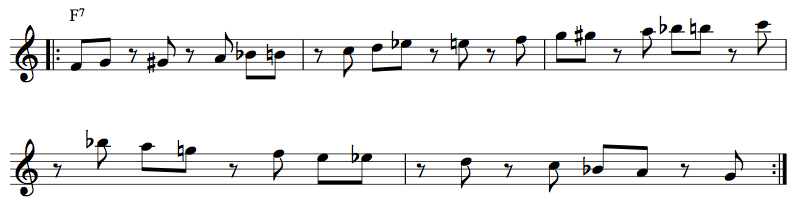

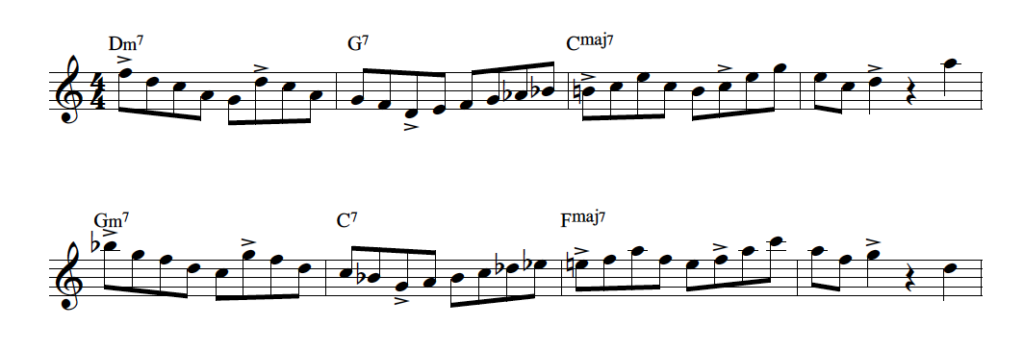

Here’s another way to explore and hear harmonic relationships over the shifting tonalities of the Coltrane Matrix. Take a look at the example below:

The main element of this melodic line is the 1-3-7 shape. To be clear, when I refer to “1-3-7” in this etude, I’m talking about the implied melodic shape itself, not the shape with respect to the actual notes of the chord symbols.

So in the first measure the line starts with a 1-3-7 shape that implies a B minor tonality. (In fact, by adding a fourth note to that shape in that measure, an F#, it spells out a B-7 chord.) The F# makes a chromatic connection to the F natural to spell out a Bb- (maj7) chord, which fits very nicely over the Eb7. The A natural then connects chromatically to the Ab in the second measure, then continues with a similar shape (1-3-7), but in a new key (Ab major). The fourth note added to that shape (D natural, which is the +11 of Abmaj7) then connects chromatically to the D# (the 3rd of the B7 chord). The rest of the notes over the B7 can be thought of as a fragment of the diminished scale, with the D natural functioning as the +9, and the C natural functioning as the -9.

The line continues in the 3rd measure with a 1-3-7- shape similar to the original one in the first measure, but with obvious alterations (specifically D# and A#), and the fourth note is a G#. The A# and G# imply a strong Lydian sound over the Emaj7 chord. The last four notes of the third. measure are also organized in a 1-3-7 shape, but again, with obvious pitch changes. The last two notes of the third measure (A# and G#) function as a +9 and-9 over the G7 chord, which then resolves to the 5th (G) of the Cmaj7 chord.

As you play through this, you’ll hear a kind of “descending chromatic” quality implied by the movement of the entire line. This is largely due to the similarities and slight variations between the 1-3-7 shapes. I strongly recommend practicing this etude with a backing track, so that you can hear the “surprises” as the 1-3-7 shapes unfold over the actual harmony. If you’d like to explore and learn more about the harmonic relationships, substitutions and novel ways of constructing melodic lines over dominant to tonic chord movement, please take a look to my e-book, The Coltrane Matrix: 40 Unique Melodic Ideas in All 12 keys.

Click on the link at the bottom to download a free pdf of this etude.