Most musicians that come to me for Alexander Technique lessons have a well-developed, highly detailed practice method that they follow. They have chosen this method deliberately, and typically follow it with an almost religious reverence.

And therein lies some of the problems that lead them to seek my help in the first place.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m all in favor of a logical, purposeful, structured method of pedagogy based upon the principle of cause and effect (as opposed to anecdotal assertions by accomplished players that aren’t based upon repeatably measurable results).

But any method, no matter how sound, has one rather obvious limitation: It can’t respond to you. It can’t modify itself to best suit your needs.

A good teacher, on the other hand, is helpful precisely because he/she responds effectively to you.

It’s all a matter of the teacher’s sensitivity of perception and communication with you, moment to moment, week to week (and longer). How you learn, what’s helping and what’s not, what you are misunderstanding, where you need more practice (where you need less!), etc.

And most important, a good teacher can notice what you’re doing with yourself as you carry out your practice. Are you straining, stiffening, compressing? Are you creating an unnecessary struggle within yourself as you play? (This is where the skill of a well-trained Alexander Technique teacher can be of enormous benefit.)

You see, most of the musicians who come to me for help do so, in part, because they’ve become inflexible with their method of practice. Inflexible both in the details of the method itself, and in carrying it out on a day by day basis.

At the very least, this leads to a sort of stagnation in progress, a sinking feeling that, “No matter how hard I try, I just can’t seem to get past this plateau in my progress.”

At worst, this rigidity with method leads to more serious problem, such as repetitive strain injuries, chronic back/neck/shoulder pain, and even focal dystonias.

I ask my students to ponder the differences between teacher and methodology. And because they are ultimately responsible for the choices they make as they practice and study, I encourage them to ultimately think of themselves as their own teachers.

I’m not telling them to ignore the advice of their teachers. I’m just telling them that it’s easy to turn their teacher’s methods into rigid, inflexible, unresponsive practice habits. It’s up to them to be vigilant, to grow into experts on themselves and their learning process as they practice each day.

To become your own teacher is a lifelong skill. It’s something you strive to get better at. It takes lots of reflection, discipline, honesty, discernment, love, commitment and great attention to detail. (That’s the same, of course, whether you’re teaching yourself, or somebody else.)

But the main thing you need is responsiveness. You need to see which component of your practice method needs modification.

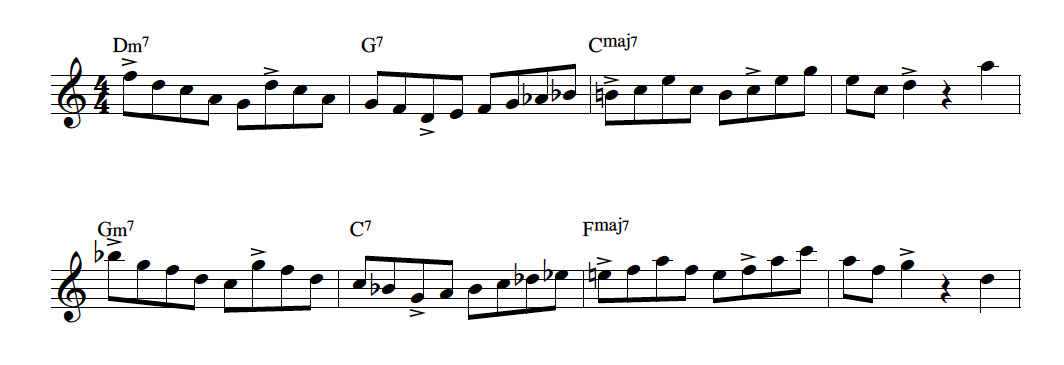

I’m very well-organized in my saxophone practice, and most definitely follow a method of learning that I’ve designed largely myself. I always have a “to do” list of particular exercises and study. Typically, this list is based upon a weekly cycle.

But a day in the week doesn’t go by when I don’t modify something from my weekly plan in my practice session. Alter a tempo, spend more time on one detail of a particular exercise, reduce or eliminate the detail of another, sometimes throw out an exercise in its entirety. (In fact, by the end of the week, the routine I started with has morphed into something quite different.)

With each component (exercise, or detail of an exercise) of my practice routine on any given day, I’m either regressing (making it simpler and/or easier), progressing (making it more complex and/or challenging), or keeping it the same.

I make my decisions on modifying (or not modifying) the components on my routine by asking myself one simple question: “Is this helping me exactly the way it is?”

If the answer is yes, then I know to keep working on it until it needs to either be modified (progressed), or dropped, from my practice routine.

If the answer is no, then I have to ask myself, “What would I need to modify right now to make this more helpful to me”?

This is where creativity comes in. If it’s too complex and/or difficult, I need to find a constructive way to regress the exercise while still maintaining the pedagogical intention.

Regressing effort is a fundamental part of the art and science that any good teacher utilizes. The better I get with regressing effort for myself, the better I get with helping my students. And the better I get in helping my students, the more efficient (and satisfying!) my own practice continues to become.

Equally important is learning to either progress an exercise or to let it go entirely. I encounter so many musicians who are spending time needlessly on things that just don’t continue to help them improve.

So strive towards being a teacher as you practice each day. Go by principle, and follow a method. Just be observant, curious and flexible. If you do so, you’ll do nothing but improve.