These days there are so many resources available to students of improvisation. Excellent books, instructional videos, smart phone apps, classes, private lessons, solo transcriptions and more, are there for the serious student (and for the not so serious student, too).

Yet there is a fundamental truth about any kind of instruction when it comes to improvising: Nobody can teach you how to improvise. No set of thoughts, or instructions, whether written or given verbally, can teach you this skill.

Why not?

Because improvisation is a creative process. You can’t teach somebody “how” to be creative.

It’s the same whether it be improvising, composing music, writing poetry or designing a new dress. Ultimately, you have to bring order to random elements. You have to be able to bring something forth from nothing. You have to be able to create.

For you to be able to create spontaneously (as an improviser does), you have to be willing and able to imagine, decide, and take action instantaneously. Though it is often deeply impacted by those with whom you’re playing (and by those who are listening to you, i.e., your audience), in the end it is all a very solitary and personal phenomenon, with the final responsibility resting squarely on your shoulders. Note to note, prose by phrase, multitudes of decisions made in the moment, both consciously and unconsciously, all shaped by your muse.

So you can’t be taught how to improvise, but you most certainly can learn.

How?

By cultivating your creativity, and acquiring the skills to turn that creativity into a sonic expression on your instrument.

As human beings we all have the capacity to create. Now, for sure, some people are born with a more natural tendency toward this than others. We might describe them as “talented” or “gifted”.

Yet the fundamental ability to imagine is a staple of the human condition, as is the ability to spontaneously create and express meaning . When you’re talking with friends, you’re improvising. Your words and gestures, organized instantly, are a manifestation of your impulses, thoughts and feelings. They flow together naturally and effortlessly.

Though the specific details are different, the process is similar when you improvise music. (For the improviser, the details can be found in the method of study.)

Tools and Skills

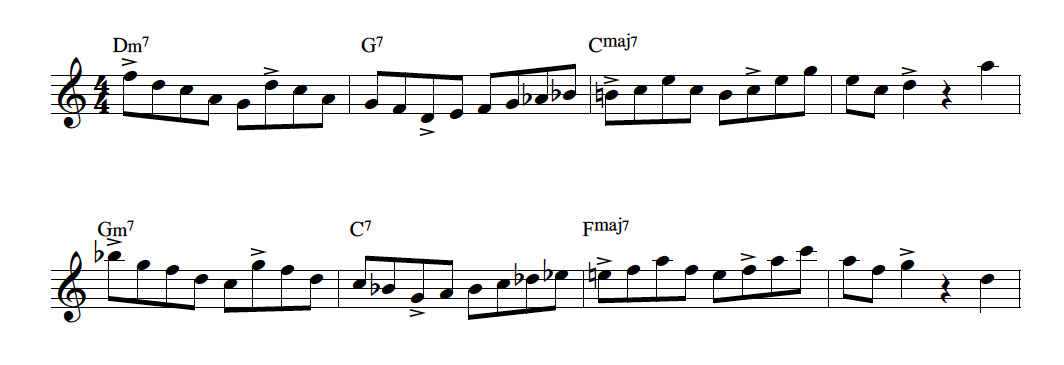

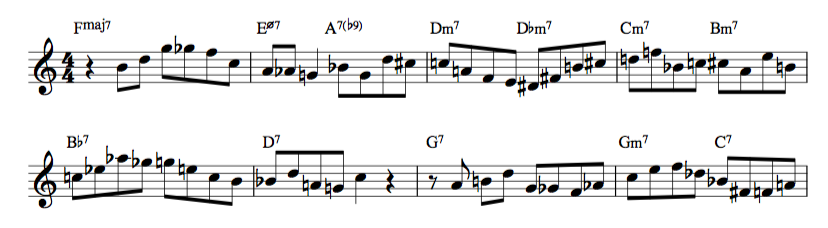

Scales and chords (and all their inversions), song forms, harmonic substitutions, intervallic patterns, rhythms, articulations, etc., are the improviser’s tools. But they, in of themselves, are not improvisational skills. You may possess great control of these “materials” of music, but that doesn’t mean you have the skill to create with them.

To be able to do that, you must practice creating with them. Regularly. This practice involves (and builds upon) three components:

1. Imagination

2. Initiation of movement

3. Response to sound

In essence, you hear/think, or otherwise follow an internal impulse of your imagination, initiate its movement (you play), and then respond to what you just played (along with responding to the interactions of the other musicians playing with you, if that’s the case). That response informs what you play next. In reality, there is no beginning or end to this sequence. It’s circular, sort of a dance. And ideally, it’s something that happens intuitively, often initiated below the level of verbal consciousness. (Though in the beginning, it can seem like an entirely deliberate, somewhat self-conscious process.)

And to be clear, it is vitally important that you constantly work on developing your tools. This will give you more material to draw upon as you create, and can even spark your creativity. But ultimately, the creative process with these tools comes from exploration and discovery.

Even transcribing solos of great improvisers can’t teach you how to create. They only show you the end results of a great improviser’s creative process. You can certainly learn lots from this (perhaps most important, how the tools “work” in action). And even though transcriptions can show you many ways creative “problems” are “solved”, they can’t teach you how to solve your own creative problems.

So How Do You Learn?

You learn by doing. You can start with even the most minimal of tools.

For example, If all you know is a C major scale, you can begin to really play with it, move with it, explore its sounds and relationships, how it folds and unfolds into various intervals, shapes, colors, etc. Make up a song with it, even if it’s with only one note of the scale. Rhythm is the heart of music. Use it to ignite your impulse to create.

And sing. Many aspiring improvisers think they have nothing in their musical imagination. Yet, in my experience teaching novice improvisers, even those who are sure they have nothing in their imagination can sing (or hum or whistle) an improvisation with a backing track, piano accompaniment, with their favorite jazz recording, or even with just a metronome. The imagination is there (though it will become more sophisticated and complex through practice); it’s just not connected with the instrument yet. Vocal improvisation is a very effective way to spark the aural/rhythmic imagination. Give it a try!

Improvise along with recordings. Never mind that you “don’t know what you’re doing”. Just close your eyes and play, follow your ear, your impulses, your sense of movement, time and rhythm. Give yourself permission to sound “wrong”, smile about it and have fun. Like a child who learns to speak from listening, you’ll gradually form meaning in what you do (especially as you study and acquire some “tools”)

Listen, listen, listen to great improvisers. Let their languages wash over you. Listen to a solo so many times, you can sing it. Then sing variations on it. Play with it.

Be kind and patient with yourself. Just as a child needs patience and encouragement when learning to speak, so do you when learning to improvise. Enjoy in the process, and make the quality of the results secondary (at least in the beginning stages).

Improvising is all about making many, many decisions spontaneously (based on values, desires, conceptions, intuitions), and turning them into sound. There is no formula for that. Nobody can do that for you . But you sure can learn to do it for yourself!