After several remote consultations in the past few weeks with various wind instrumentalists, I’m reminded again about a pervasive misconception that many musicians who work conscientiously on growing and improving their sound tend to cling to. (I’m thinking most specifically about wind and string players, but this applies to any instrumentalist.)

Put simply, improving and cultivating one’s sound is a”physical” process.

I put the word physical in quotes in order to emphasize the way some musicians understand and approach the concept of tone production.

To be sure, there are many physical components that must be addressed to producing your best sound. But thinking of how to produce your sound in a way that is satisfying to you, expressing that which you wish to express, is much more than a mere physical process.

It’s a whole person process (or as we’d say in the Alexander Technique, a psychophysical process).

This means that acqiring the skills necessary to obtain your best sound involves all of you: body, mind and spirit. (Here, I define spirit as the “non-physical part of a person that is the seat of emotions and character”.) This whole you is one, functionally integrated being.

And in expressing your sound, it all begins with imagination.

If you were to ask the right questions to the best wind instrumentalists in the world about how they get their beautiful sounds, you might hear some conflicting answers, where pedagogy is concerned:

Do this with your soft palate (as opposed to that, which is what another great musician does to get his/her sound)

Do that with your tongue (as opposed to this, which is opposite of what another great musician says about getting the best sound)

And so forth…

But one thing all of these world-class instrumentalists can agree upon about producing their best sound is also the one thing they all have in common:

A vivid, detailed imagination of how they would like to sound.

The fine motor skills involved in producing a beautiful sound, with all the nuance, shading, subtleties, power and reliability is a response (which is cultivated over the long-term) to how you imagine your sound.

That’s how your brain works.

It’s not really that different from how a child learns, not only the words of his/her mother language, but also the prosody, pronunciation, accent, constituencies, etc.

The fine motor mechanisms of speech come into play to fulfill the child’s imagination and conception of of the sound qualities of language. He/she doesn’t need to consciously direct these mechanismsin order to make that happen.

One of the biggest stumbling blocks that I encounter as I coach musicians who have come to me for help in improving their sound, is that all the work to produce their sound has been reduced in their minds to a mechanical concept. For example:

Me: What do you think of as you aim to produce your sound?

My client (a French Horn player): I think of holding my corners in and starting the sound as if my tongue were connected to my diaphragm.

Me: What about the sound itself? How do you imagine it?

My client: I imagine it being supported by my breath and controlled by a clear, focused airstream.

These are all good things to wish for.

But I asked this particular client to consider them as being of secondary importance. Secondary in that they are things that should be in support of, and responsive to, how vividly she actually imagines her sound. What she wishes to express in the sound itself.

Because the truth of the matter is that though these things are vital, they in of themselves don’t produce her best sound, if they are not called into play by her imagination and desire.

(I’ve yet to encounter a musician who as sought my help in tone production related matters who isn’t markedly lacking in the kind of aural imagination I’m advocating here.)

Embouchure muscles, as well as the other muscular mechanisms involved in producing and voicing sound, can adapt much quicker than you might think they can (this is especially true where strength is concerned).

And you’ll have a much better chance of “strengthening” these muscles in the most specific way possible if you place your imagination first.

Here are few things to keep in mind to help with this:

- Listen deeply-Spend lots of time listening to other artists who play your instrument whose sound you deeply admire. Not so much to copy what they do, but to really ignite your curiosity about what makes their sound so wonderful, what makes it touch you so deeply. Take this kind of listening into the practice room with you as you work on your own sound.

- Imagine explicitly-If you spend lots and lots of time listening to great artists, see if you can hear and describe in detail the things you like about their sounds. The attack, the color, the release, the shading…put it into language that makes sense to you. Bring those words to mind as you wish for your own sound.

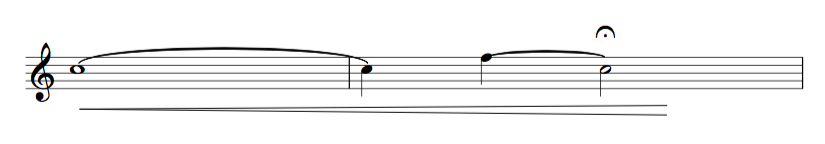

- Transcribe-Find a recording of somebody that epitomizes the beauty in tone you aspire to (or are inspired by). Let it be something that is simple, lyrical, and clearly executed. Take out your instrument and aim toward emulating it one phrase at a time. Make it as specific a copy as you can. In learning to imitate another artist this way, you’ll learn tons about how to hear and produce the sound you imagine.

- Listen outside of your instrument-This ties into the other processes of listening mentioned above. Learning to recognize, describe and imitate tonal beauty in an instrument other than your own not only grows your imagination, but it also deepens and clarifies the concept you already have of your own sound.

- Sing-To sing you must first hear and imagine clearly. To paraphrase the great improvising pianist and music educator Ran Blake, “…when you hear a singer, you are hearing the purest form of their aural imagination…” So practice actually singing the kind of sound you’d like on your instrument. It will help in a multitude of ways.

- Hear and accept-No matter where you are in your journey with your sound, accept it and love it for what it is. Just like your own child, you already love them as they are, even though you know they will continue to grow and develop. Be the same with your sound.

So continue to work on the mechanical components of getting your best sound, but put imagination first, and see how your brain and body (all of you, actually) come into play to serve your desire.