There are so many resources available now for improving your ear, both for general musicianship, and more specifically for improvisation. One simple little device that can be immensely helpful is a drone. (I’m of course talking about a device that makes a continuous humming sound, not the aircraft.)

There are so many resources available now for improving your ear, both for general musicianship, and more specifically for improvisation. One simple little device that can be immensely helpful is a drone. (I’m of course talking about a device that makes a continuous humming sound, not the aircraft.)

In the past few months, I’ve been spending a little time each day of my practice session using a drone. Besides the improvements I’ve gained in my harmonic imagination, intonation, etc., I’ve simply been having a blast playing with it, and wanted to share some of my ideas and experiences with you.

There are three main skills in which practicing with a drone will help you improve and expand upon:

- Intonation

- Harmonic recognition/imagination

- Rhythmic imagination

Let’s look at these one at a time.

For intonation, playing long tones, melodies, overtones, etc., with a drone is far more effective than practicing with a visual tuner. Learning how to hear and respond immediately to the necessary changes in voicing is fundamental to any wind instrumentalist. (Notice that I said “hear”!)

By practicing long tones with a drone you rely completely upon your aural senses and let your brain know what to do to voice the note most effectively. It’s almost fail proof. All you have to do is play with the drone and cancel out the unpleasant waves you hear. You don’t even need to know specifically what you did physically to make the changes. Just trust your ear and your brain.

A great and really fun way to improve the accuracy of your harmonic ear (as well as to expand it!) is to practice simple improvisation explorations with a drone. By perceiving the drone as a particular point of reference, you can systematically (or randomly, if you prefer) give yourself the experience of hearing how different pitches relate to it.

Here are a few examples of how you can practice this way:

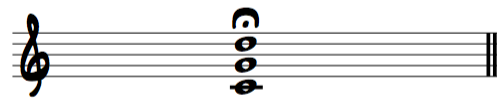

- Use the drone pitch as the root of an assigned key center. For example, if your drone is a concert “C”, practice improvising simple melodies with the various tonalities of “C”: major, melodic minor, harmonic minor, Lydian, harmonic major (pentatonic scales, including major, minor and harmonic major), etc. Play around with changing key colors in your improvisation (e.g., going from major to Lydian; melodic minor to harmonic major, etc.) Listen, and enjoy, as you connect intention with aural precision.

- Perceive the drone pitch as various degrees of a particular scale. So think of a “C” drone as the root, 2nd, 3rd, etc., as you improvise in a particular “C” tonality. You’ll learn to hear and imagine scale degrees in relation to your melodic statements.

- Explore the drone as various altered tensions. You can do this with a scale or chord in mind. For example, you can perceive your “C” drone as the raised 11th of the key of F# major (as a B#, actually), or as the flatted 13th of an E7 chord. By playing around with these tensions this way, you’ll develop a more vivid harmonic imagination, turning “altered tensions” into an actual aural experience instead of a just a theoretical idea.

- Drone over a standard song. Choose a tune that is both harmonically complex and enjoyable to improvise over, and set the drone as the tonic root note. Practicing this way will help you to really internalize the modulations found within the harmony of the song.

- Have no specific key center in mind. Yes, just improvise/explore freely, noticing how certain combinations of notes work over the drone. Learn to get comfortable with (and recognize) various degrees of dissonance. Just let your mind run free and see what you discover. Or maybe make variations on a simple intervallic pattern.

Practicing with a drone can also really open up your rhythmic imagination. The constancy of the drone sound acts as a kind of support for you to push against, yet provides no specific rhythmic stimulus. At first, this can seem kind of challenging, as perhaps no kind of rhythmic movement comes immediately to mind.

But after even just a short amount of practice, you’ll find yourself imagining and playing multiple rhythmic pulses. As you spend even more time, you can explore various types of odd-metered groupings and time feels, modulating tempos and more. Practicing this way will make rhythmic variation much more available to you as you improvise.

And if you like, you can also practice with a drone and a time source (either a drum loop or metronome) at the same time. This is not only immensely helpful in opening up possibilities, but also, is very meditative, engaging and calming.

It’s not hard to get access to some good drones, these days. Here are a few resources:

I use two different smartphone/tablet apps. I have an iPad, and my favorite is RealTanpura, which simulates the four-stringed drone instrument used in Indian classical music. I like it because it has a beautiful sound, and I can change the pulsation of the drone, as well as choose various other modes (harmonic organizations), speed, pluck rate, etc.

The other app that I use from time to time is Scale-Master, which is a synthesized drone, but comes with various features that are useful, like being able to create specific intervallic drones, and a large range of frequencies.

Recently I’ve been using DroneTone, which has a sampled cello sound. Rich in overtones, it has been particularly helpful for dialing in my intonation/voicing on saxophone.

Whichever you choose, if you start daily practice with a drone, you’ll discover all kinds of new ways to think of and hear music. Your ear will improve, and you’ll have lots of satisfying, highly enjoyable playing experiences.

And if you know of, or use, an app that you think is particularly good, please let me know about it!