“Many people think that how they commit to the metronomic beat is the only game in town. But in bebop, the game in between this beat and the next one is really the main game.”

-Charles McPherson

“The metronome is not my sense of time. My sense of time lies between the metronome clicks.”

-Bill Plake

Well, I have at least one thing in common with alto saxophone great Charles McPherson. We both agree about our relationship to time (and how we perceive it).

Many musicians who seek my help in improving their sense of time and rhythm tend to have this more “passive” approach to the beat, as described above. This is, in part, because they view playing with “good” time as some kind of burden, as something they are obligated to do in a rather precise and inflexible manner.

But playing with “good” time is not a burden. It is a liberator, making your music more vivid, along with optimizing your skill and coordination.

And for you to play with “good” time, you need to be flexible and dynamic in two specific ways:

First, you need to be flexible and responsive to the time/rhythm/feel nuances of the other musicians with whom you’re playing.

Second, you need to have a dynamic rhythmic imagination.

It is this “dynamic rhythmic imagination” that I wish to address here.

No matter what kind of music you’re playing, “between the beats” is where all the possibilities lie. If you’re playing “interpretive” music, lets’ say, Bach, for example, it is your imagination of the “unevenness” (the emphasis and de-emphasis) of each of the eighth notes in a particular phrase that give it a unique expressive quality.

In other words, it is how you “imagine” the eighth notes relative to the beat that puts your personal stamp on the music.

If you’re an improvising musician, on the other hand, it’s not just how you imagine the eighth notes relative to the beat, but also what you imagine rhythmically.

By “what”, I’m talking about the complexity and richness of your rhythmic expression. I’m talking about more than just continuous eighth (or sixteenth) notes.

Syncopation, polyrhythm, metric modulation, polymeter…even silence…all of this can be part of your rhythmic imagination. The “game in between this beat and the next one”, as Charles McPherson says.

And for sure, as an improvising musician, the “how” of how you play your eighth notes, sixteenths, etc., relative to the beat, is a vital component of your expression. (I think of this as a part of your “time feel”.)

But the bottom line is that none of this happens without consciously strategic and constructive work. In the simplest sense, that means working on two specific skills:

- Your sense of pulse (your ability to imagine and accurately predict) the beat (or “clicks” on the metronome).

- Your ability to imagine and move with an ever-expanding vocabulary of rhythmic expression relative to that beat.

The key word here is imagination. When you’re practicing, that might mean using a minimal amount of metronome clicks relative to the rhythm being explored.

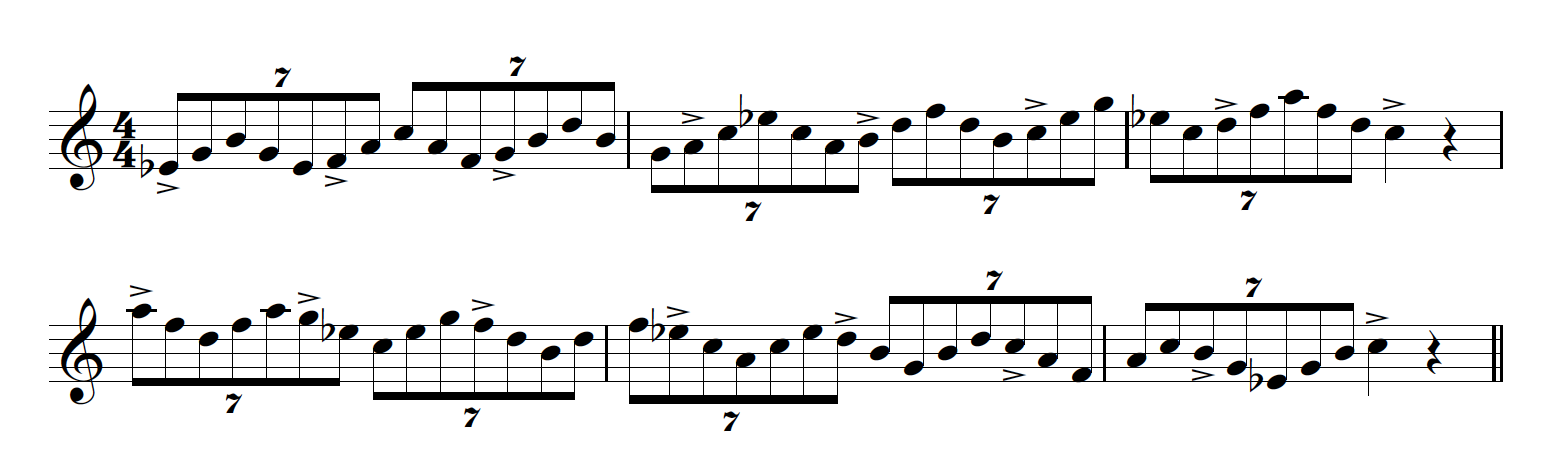

So for example, if you’re working on feeling eighth-note septuplets (seven notes played within two beats), it would make little sense to set the metronome clicking on each eighth note of the septuplet. Doing so might make your eighth notes sound “more even and precise”, but will do nothing for your rhythmic imagination. Ultimately, it is your carefully cultivated “rhythmic imagination” that will make your rhythms most precise, whether your playing by yourself or with others.

It would be more beneficial to set the metronome click in three ways. From easier to more challenging, these are:

- One click per each septuplet.

- Two clicks per each septuplet. (Believe it or not, you’ll most likely find this to be a bit more tricky.)

- One click per measure. (So, in 4/4 that would be one click for every 14 notes)

Once you’re able to do all this fairly readily, next would be to displace the click of the metronome relative to the septuplets, perhaps having it click beat two of each measure (or if you’re really up for a challenge, having it click on the “and” of beats one and three!)

Working on rhythms with this kind of intention and precision yields remarkable results, whether you’re an interpretive or improvising musician. The music “between the beats” comes alive inside of you with sometimes startling energy!

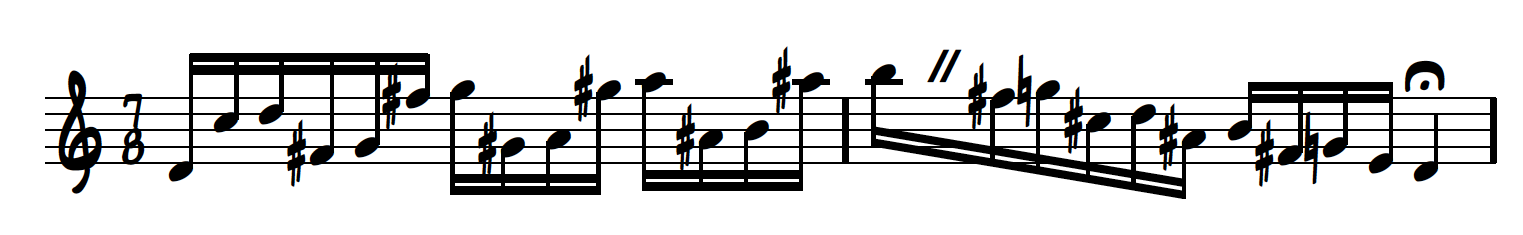

I’ve composed an e-book filled with exercises to help you enrich your rhythmic imagination, as well as to improve your ability to predict the beats. Working daily in this way will help you build measureable skills that apply to whichever kind of music you play.

In any case, I encourage you embrace Maestro McPherson’s assertion, and discover the magic between the beats. Here’s a link to Ethan Iverson’s excellent interview with Charles McPherson. Enjoy!