It is often said about the great jazz trumpet player, Miles Davis, that a large part of his improvisational genius manifested itself not only in what he played, but also in what he didn’t play.

It is often said about the great jazz trumpet player, Miles Davis, that a large part of his improvisational genius manifested itself not only in what he played, but also in what he didn’t play.

His use of silence became an integral color of all his improvisations. It was largely responsible for keeping us, the listeners, on the edge of our seats, never knowing what to expect next.

The same could be said about many other iconic jazz improvisers: Lester Young, Charlie Rouse, and Chet Baker, to name but a few.

Yet as much as students of improvisation admire this concept, very few seriously consider it and actively pursue it through reflection and methodical study.

And that’s too bad. Because you can use silence quite effectively to create compelling improvisations, as well as to really put a stamp upon your own personal style of expression.

Keep in mind that whenever you take an improvised solo, that solo is defined by the sum total of what you play, and what you don’t play, whether you’re conscious of that, or not.

So it’s probably a good idea to become conscious of how you use silence as you improvise.

Silence is a color in music with limitless possibilities.

You’ve probably had at least one experience of being bored (or overwhelmed!) by the relentless barrage of notes that some (less mature) improvisers put upon your ears.

No contrast, no flexibility, no breathing room, no surprises. Not exactly the elements of an expressive, refined improvised solo.

On the other hand, you might remember being absolutely swept away by the drama and suspense of the sparse simplicity used by a master improviser (such as Miles, for example).

It is fairly simple to begin to shift your thinking about silence in relation to sound. Just start with this idea:

You are not obligated to fill every moment, every measure, every beat, with sound.

In fact, what if you were to approach your solos with a different kind of obligation?

What if you’re only obligation as a soloist was to be mindful of silence (your silence, that is), and the sounds you make with respect to that silence? What if whatever was being played (or not played) by the ensemble without you was already beautiful? What if whatever you played, you chose to play in order to enhance that beauty?

How would that change the way you play? How you construct your solo? How you interact with the other musicians? How you use your sound? How you perceive yourself? How you hear the whole, instead of the parts?

If you approached each solo with this kind of respect for silence in mind, it would most likely get you to do at least two things differently:

1. Listen more carefully (to the rest of the ensemble, as well as to yourself).

2. Play more intentionally (following your inner ear, your muse, all in response to the other musicians).

Think about that. Those are two excellent, highly desirable traits for both a soloist and an accompanist.

You can methodically practice and explore using silence and space in your solos. Here are a few simple things to get you started:

- Listen to the masters-Start by opening up your consciousness to how effectively silence is used in constructing a solo. Find somebody with this quality whose playing you really admire. Listen and analyze.

- Assess-Listen to recordings of yourself improvising. Try to hear yourself in a variety of contexts (different styles, ensembles, etc.) Assess your own use of sound and silence. Notice any habitual patterns. Notice any phrases that you play that sound unintentional or superfluous. Notice where you start and stop to begin and end a phrase (again, noticing habitual, predictable patterns).

- Listen without playing-Choose a song form to improvise over (a standard, blues, etc.) Use a backing track or just put the metronome on. Have your instrument in hand, ready to play. Let an entire chorus go by as you listen (whether to the backing track, or to the metronome, as you internally “hear” the song form), holding your instrument, but not playing. See if you can do this and still imagine and improvised solo in your mind. What do you “hear”?

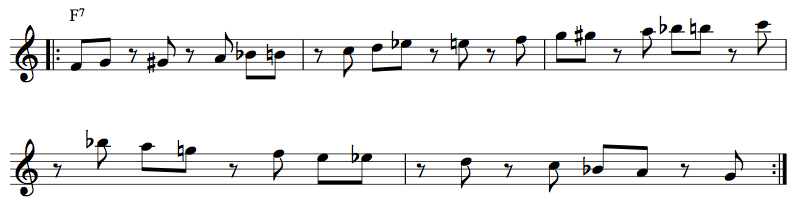

- Limit phrases per chorus-Take this same song form and allow yourself to play only one phrase per chorus. It can be anywhere in the form, and as long or short as you like. improvise over several choruses this way. When you’re satisfied with what you’re doing, move on to playing several choruses with only two phrases. And so on, until you sense that you are “hearing the silence” as well as choosing your lines with more intention.

- Use small rhythmic cells-Now take this song form and use small, simple rhythmic cells. Maybe start with two eight notes. Again, it doesn’t matter where you place them in the bar (or form), but you’re limited to just these two eighth notes that have to be followed by at least one beat of silence (preferably more).

- Assign silent “rhythms”-Now use specifically assinged silences at various, random places over the same song form. Start with even numbers (half rests, whole rests), then move on to odd numbers (one and half beats; three beats, or more) to add a polymetric element in your solo.

- Reassess-Record yourself improvising over the song form with no agenda in mind, and then listen. What did you notice? Did anything change? What did you like? What would you like to change?

So embrace silence as a new, almost exotic color and possibility for you to explore. Silence makes the notes you play sound more intentional, more meaningful, more powerful, more expressive.

I’ll leave you with something the great alto saxophonist Lee Konitz said about taking a solo on the blues, in which he didn’t play a single note on one entire chorus:

It was the best chorus I’ve ever played…