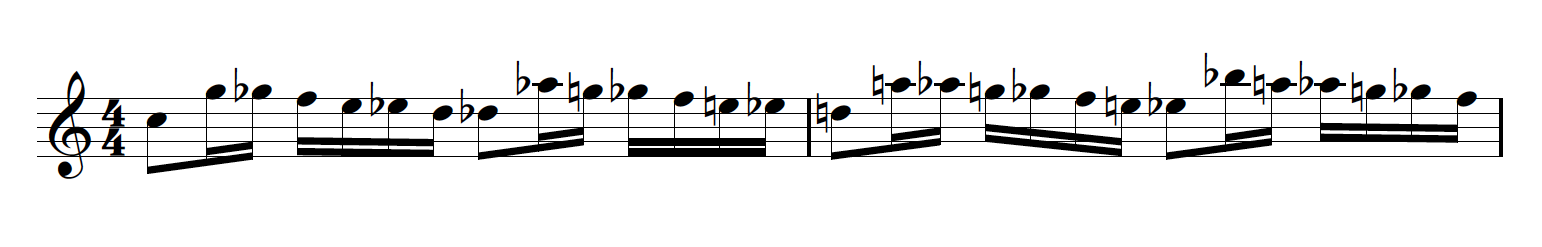

Part of the work in studying improvisation is what I call “feeding” our ears and imagination. In essence, this involves learning and practicing new patterns and sequences.

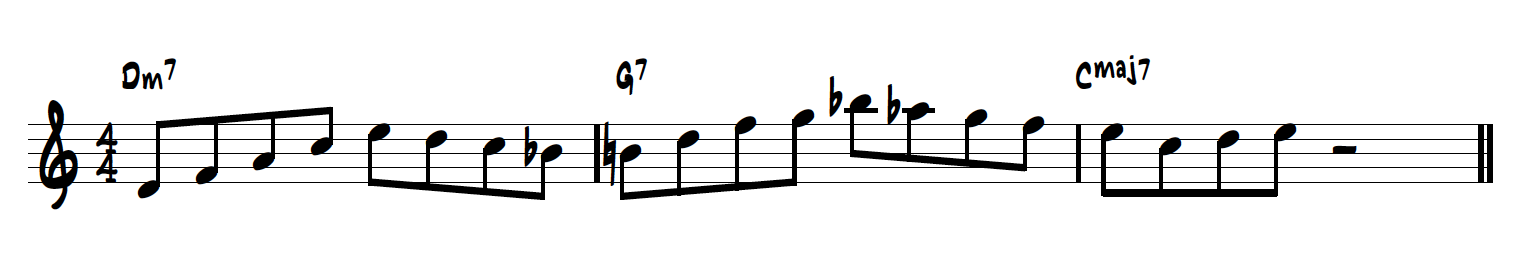

These patterns can be anything from simple, diatonic melodic movements, to more harmonically complex polytonal statements that you’ve discovered in a jazz etude book, to very particular “licks” that you’ve transcribed from somebody’s solo.

All good.

And all things that will ultimately increase your improvisational vocabulary.

Whenever I give a lesson to any intermediate to advanced improvisers, I typically find that they are already practicing patterns on a regular basis. (I can hear it manifest itself as part of their improvisational “vocabulary”.)

Yet far too many of them are not doing one very important thing each time they learn a new idea, lick or pattern:

They’re not singing it first, before playing it.

As simple as that.

I begin to suspect this based upon what I hear in their playing, which in general, sounds like they are somewhat disconnected to the notes they are playing. In short, it sounds like they’re not playing so much from their aural imagination, as from mechanical memorization.

As I start asking questions, I often find that they also don’t do much singing in general as they practice improvisation.

And that’s where we begin to change their practice aims and procedures.

You see, there is a very good reason all the legendary jazz artists would learn so much of their vocabulary by ear (and why this learning tradition is carried on by today’s great artists and educators).

It all comes down to how you think and react.

When you think of a melodic idea in a mechanical sense (such as, “root, to flat 5, to 4, to flat 3, to natural 3, to root”, for example), your brain organizes how you’re going to play that idea (your reaction) in a fundamentally different way than if it emerged from your aural imagination.

When you practice patterns from this more “mechanical” organization, it not only takes a good deal of time to “get the notes under your fingers”, it also takes a long time to find its way into your natural, organic improvisational expression.

On the other hand, when you are able to hear clearly and precisely how a melodic pattern sounds, you will not only get the notes under your fingers in a shorter amount of time, but you’ll also be able to access the pattern more readily as you improvise.

And here’s the bonus part:

When you learn patterns primarily by hearing and imagining them, you become much more flexible with how you use them. This means that you easily learn to make variations on them in the moment when you improvise (which, in many ways, is the essence of improvisational variation).

By using you ears in this way you turn patterns into components of aural imagination and impulse. This becomes the fuel that privides energy and movement for your improvisations.

When you first start learning patterns by ear, it can seem daunting. It might take a lot of time to learn even the most rudimentary melodic patterns (like 1,4,5, 3 in major keys for example).

Keep in mind that you get better and better at doing this (meaning faster and more accurate) the more you practice it. And also keep in mind that you can start simple, building upon your skill.

But here’s the bottom line:

No matter whether you discover a new melodic pattern (or lick, or sequence, or idea, or fragment, etc.) that you want to learn from a recording, or from a notated source (such as a transcription or jazz etude book), get in the habit of doing this one very simple, very important thing:

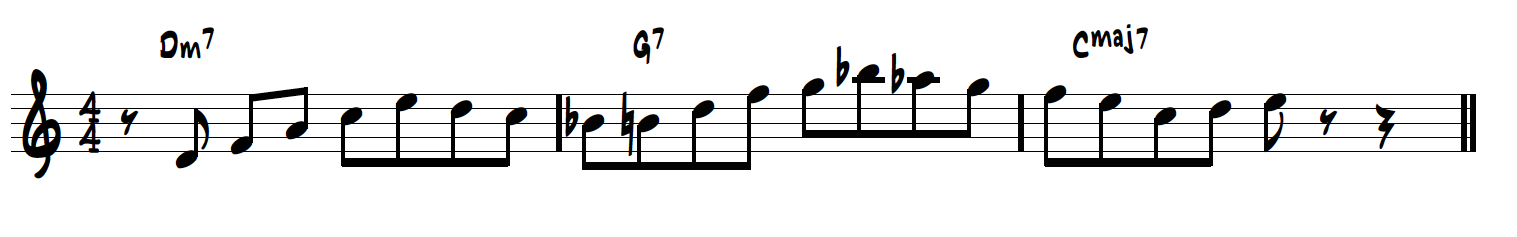

Take the time to sing the pattern with 100% accuracy before you take it to your instrument to work on it. Don’t just approximate the general “shape” of the pattern. Know it from note to note in its entirety.

Sing it in at least one key, but sing it until you have confidence that you imagine and hear it with vivid clarity. Let it go deep inside of you.

It is never time wasted.

And even if you’re practicing patterns from a book that presents a particular melodic pattern in all 12 keys, take time to sing the pattern in an iteration that fits within your vocal range. Then start wherever that is on the page and work each of the other keys of the pattern using your “singing key” as a starting point.

Doing this regularly will help you to play and absorb the pattern in the other keys more readily and more deeply.

It’s a matter of turning the somewhat abstract (the notes and sequence of the pattern, lick, etc.) into something a bit more concrete (your expression).

And when that happens, you’re on your way to expanding and personalizing your own unique improvisational voice.