Improvisation can seem like a mysterious, almost impenetrable process to those new to studying it. The idea that a musician can generate cogent, beautiful melodies on the spot seems almost superhuman. But in fact, it is one of the most human characteristics we possess.

Improvisation can seem like a mysterious, almost impenetrable process to those new to studying it. The idea that a musician can generate cogent, beautiful melodies on the spot seems almost superhuman. But in fact, it is one of the most human characteristics we possess.

We’re actually natural improvisers. We speak and move spontaneously everyday with no real struggle or wonder about the process. In short, we improvise. Mostly we do this because we practice doing it everyday (it’s called living).

Yet when it comes to musical improvisation, we can sometimes find ourselves in a state of doubt. (This is because we don’t yet have enough specific experiences to strengthen our faith.) For something as seemingly complex as jazz improvisation it is easy to get overwhelmed with where to start and how to proceed. There are so many elements to deal with: tonality, harmony, song forms, time and rhythm to name a few.

I notice that many people who are new to studying jazz make one fundamental mistake: They place far too much emphasis (and study time) on trying to figure out which notes to play as they improvise:

“What should I play over this chord?”

“Which scale ‘works the best’ with that chord?”

“What are the ‘hip’ notes to play on the blues?”

“Is it okay to play F natural over a C major seventh chord?”

Now, for sure, you have to pay attention to note choices, tonal colors, harmony/scale relationships, melodic construction and the like. These are absolutely fundamental to the expression and language of jazz, and studying them requires a huge commitment of time and will.

But studying the tonal aspects alone neglects the most fundamental elements of making jazz sound like jazz: Time, feel (this includes articulation and sound), rhythm, meter and form. You need notes to make music, but you really, really need rhythm. Many things make a jazz artist distinctive, but it’s the artist’s feel, sound, sense of space and form, and rhythmic conception that creates the most immediate, visceral distinction.

Your first goal as a jazz musicians should be on moving the notes. Again, time, feel, rhythm and form. You might know all the music theory in the world, but if you can’t create clear, intentional movement with it you’re going to end up being one frustrated musician.

These days it can safely be said that jazz is a vast, ever expanding language. There really is no such thing as a series of notes (a lick, phrase, etc.) that by itself sounds like “jazz”. What gives it the jazz sound is how it is played. What is the rhythmic feel? What is the expressive intention?

You can play an excerpt from a Bach sonata with an intention of making it sound like jazz, and it will. You can also play a Charlie Parker solo with no clue about the jazz language (or with another, specific, “non-jazz” intention) and it won’t sound like jazz at all.

When I first fell in love with jazz, I didn’t think about notes at all. I used to play completely by ear, “faking” my improvisations. I never gave a thought to the notes I was playing, I just let my ear take me places (I learned early on that if a note sounded bad against what the band was playing, all I had to do was move it up or down a half step and I was fine).

I was more interested in sounding like I was a jazz saxophonist, so I mimicked some of the great jazz saxophonists by how they were moving the notes they were playing. By how they made the notes feel.

As my curiosity grew, I began to study rather extensively my chords, scales, harmonic relationships, etc. My playing grew exponentially, because no matter what I learned, I could immediately express it through my feel and intention. I began to understand what I was doing (and hearing!), and I was also finding so many other melodic possibilities. It was like all that “fake” jazz I’d played set up a marvelous foundation to take on all this new “note” information.

So if you’re new to jazz improvisation, by all means study your chords, scales, harmonic relationships, etc. This is the material of improvisation. But make your main focus be time, rhythm, feel and form. (You’ll find that all these elements are related and support each other).

Here’s a few things you can do to start cultivating these skills:

- Listen, listen, listen-Listen to as much jazz as you can. Find players of your instrument and other instruments and listen very carefully to how they make the music feel. Notice, time, rhythm and articulation.

- Sing-Find a particular solo that you really like and listen to it over and over until you can accurately sing it note per note. This takes a great deal of time but is so worth it. Not only will it improve how you understand and conceive the feeling of jazz, it will hugely improve your ears for hearing pitch.

- Work on two-bar phrases-With your metronome set on beats 2 and 4, practice improvising phrases that fit into 2 bars. If you can’t think of any of the top of your head, take time to write some down. Use eighth and quarter notes to make phrases that are easy to hear and internalize. Aim for musical. You want to get to the point where you can feel a two-bar phrase with no thought at all. This will come in very handy as you start improvising over more complex forms (like standard songs, or the blues).

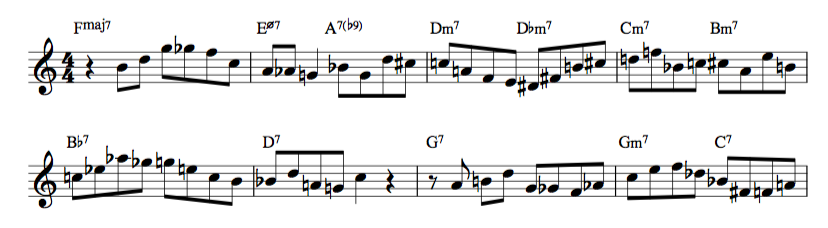

- Play jazz etudes-There are so many resources on the Web to find good, free, jazz etudes. It is also worth it to buy a nice jazz etude book. Randy Hunter has very nice material for the beginning improviser, as does Greg Fishman. You can also play any transcribed jazz solo that makes you excited. Remember, feel is the essence.

- Practice whatever you already know with a jazz feel-Whichever scales, arpeggios, phrases, etc. that you easily know should be played with your new, ever developing jazz feel. Make sure you’re working on something you know so well, that you can give most of your attention to your time and feel.

So put feel, time, rhythm, and form first. Make tonality a very, very close second, and you’ll start to sound like a jazz musician in no time.