To improvise fluently, expressively and authentically, you need to develop good ears. You must be able to find the notes on your instrument that you’re hearing in your head (immediately!) as you play from moment to moment.

So it’s no wonder that ear training is a significantly large component in the study of jazz. Learning to recognize (and sing) intervals, chords, scales, rhythms, melodic patterns, etc. (not to mention transcribing solos.), is essential jazz pedagogy. If you’re a dedicated student of jazz (or virtually any other form of improvisation) chances are you’ll spend the rest of your life refining your aural abilities. And that will pay off in a big way.

But as important as it is, a good ear alone will not insure your growth and improvement as an improvising artist. For that to happen, you have to also develop another very important component: imagination. All the ear training in the world won’t do you much good if you can’t imagine (hear) anything to play.

The great tenor saxophonist, Joe Henderson, was known to have exceptional ears. He could effortlessly and immediately play back anything he could hear or imagine (or anything any musician could play). Yet he also spent his entire life continuing to practice the materials of music: scale patterns, inversions of arpeggios, melodic sequences, interval patterns, rhythmic patterns and more.

Why would he find the need do this if he had such splendid ears? So that he could continue to expand his musical imagination.

Ears and imagination. These two components go hand in hand, of course, and one really helps the other.

Take solo transcription, for example. If you transcribe a solo from a recording, you challenge your ears. The more you practice transcription, the easier it becomes. You go from struggling to hear things note by note, to recognizing patterns, melodic cliches (“licks”), chord and scale inversions, harmonic substitutions…entire chunks of music at a time.

But you also get more from the transcribing process. By listening to and analyzing a beautifully improvised solo, you also get a chance to look inside the mind of a great improviser. You get to see how this artist thinks about using the materials of music.

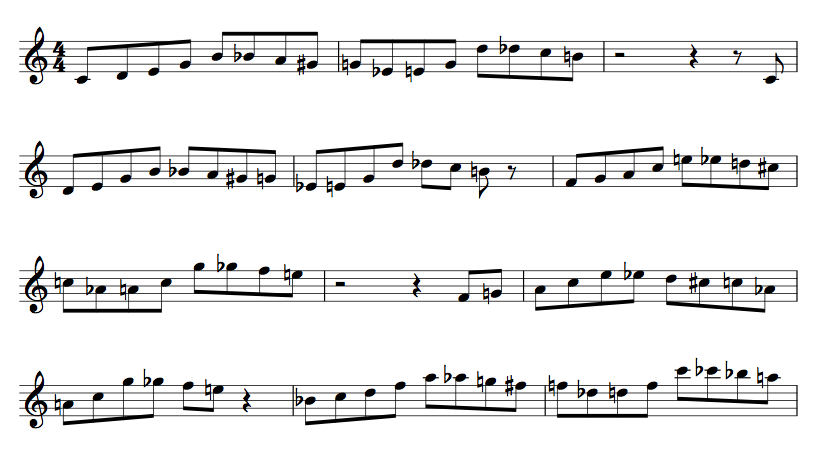

Let’s say you find a line in the improvised solo that you especially love. As you sit down to analyze it, you might find that it’s nothing more than a way of organizing the notes from a particular scale (that you already know very well) in a way that you’ve never considered.

From there, you would perhaps make a little exercise out of this pattern you’ve discovered, putting it in all 12 keys. Nicely done. Not only have you improved your ability to find pitches on your instrument (your ears), but also, you’ve expanded your conception of what is possible for you to imagine.

This is a matter of coupling your aural skills with your intellect, and is essential for you to continue to grow as an improvising musician.

When teaching improvisation, I want to hear two things in the first lesson: how you improvise as you play your instrument; how you improvise as you sing. This always gives me a good starting point.

Do you sing a beautifully clear, harmonically sophisticated, melodic and expressive solo, but have a hard time finding those same pitches and rhythms on your instrument? If so, your ears need to catch up with your imagination. (You might also need to address your instrumental technique.)

Do you improvise with reasonable fluency on your instrument, but sound like you’re thinking, instead of feeling, what you’re playing? If this is the case, your singing will most likely be far less sophisticated harmonically than what you express on your instrument, showing a definite lack of aural imagination.

Does your time feel and rhythmic conception on your instrument match up to what you sing as you improvise? How is your phrasing different from voice to instrument?

Even after you’ve effectively addressed any imbalance here, you must ultimately continue to develop both your ear and your imagination if you want to grow.

Some things you can do to improve your ear:

- Learn to identify all the intervals, scales, and chords by ear (nowadays there are great smartphone apps that help you do this at a really low cost)

- Practice sight singing, solfege, etc. (in other words, be able to sing what you’ve learned to aurally identify)

- Transcribe other people’s music (solos, melodies)

- Transcribe yourself (both singing and playing)

- Play along with recordings where you have no idea of key center, harmonic progression, etc. (try to simplify what you do to find notes that seem consonant with the recording)

- Play something by ear everyday, even if it’s just simple, familiar melodies (folk songs, children’s songs, etc.)

- Compose melodies by ear (no help from your instrument)

Some things you can do to expand your imagination:

- Always be thinking about new ways to organize scales, arpeggios, intervals, etc. Use your intellect. Think in numbers if you like. Ask yourself, what would it sound like if…?

- Listen to lots and lots of music, especially music that’s outside of your improvisational genre. Examine different disciplines, cultures, time periods, etc.

- Transcribe other people’s music (yes, I’ve already mentioned this above!) It’s important to remember that when you transcribe, you’re improving your ear as you develop your musical intellect.

- Find some good etude books for improvisation. Nowadays there is a wealth of excellent material to get you to think of tonal organization, harmony, thematic development and rhythm in increasingly sophisticated ways.

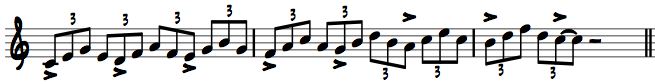

- Study rhythm. Find books to work out of. Explore odd metered music. Figure out ways to turn your “4/4” ideas into odd numbered groupings. A great rhythmic imagination is the ultimate improvisational tool.

- Practice etudes written for instruments other than the one you play. John Coltrane used to practice harp etudes.

- Take a lesson from a great teacher. You’ll probably go home with month’s (if not year’s) worth of valuable homework.

- Write your own etudes. Try composing solos over standard chord progressions, for example. This is a great chance to use your intellect and imagination to fatten your ears and clarify what you feel musically.

Above all remember that you can only play what you can imagine, and that you’ll play at your greatest potential when your imagination grows as your ear improves.