“A man’s a genius just for looking like himself.”

-Thelonious Monk

When I first fell in love with the idea of playing music, it was because I wanted to play jazz. And the thing that impressed me the most about my favorite jazz musicians was how authentically they expressed themselves. It was like you could “see” who they were as human beings simply by listening to the sounds they were making. Often you knew just by they way they played a single note.

I wanted that magic more than anything I’d ever wanted before in my young life. I wanted to be able to let something deep inside me come out to show the world who I was, the way my jazz heroes did.

So I began serious study of the flute and the saxophone. I practiced diligently and thoughtfully, really putting in the time and effort.

But it wasn’t long into my studies when my motivation began to transform. It shifted from the idealized notion of “what I wanted to do”, to whether or not what I was doing was “good” or “bad”, “right” or “wrong”, etc.

Of course this is normal, and it made sense at the time. I really wanted to learn to express myself, and there must be a single, correct way to do so (or so my young mind thought).

The up side of this shift was that I became aware of all the things I had to address in order to be able to develop the skills I needed to express myself.

But as the years passed, some unintended consequences came along with this emphasis on looking for what was good or bad, or right or wrong, in my playing. In short, I’d lost touch with that original, beautiful motivation for why I wanted to play in the first place.

I’d lost touch with the magic.

There was not a single thing that I did as musician that felt exclusive (or deeply connected) to me. My sound was pleasant and full, my technique solid, I could improvise reasonably skillfully in a variety of styles.

But there was nothing in what I played that felt like it was that same “me” that wanted to play music in the first place those years before.

It was a strangely unsatisfying feeling. On the one hand I was playing “pretty well”, getting gigs and playing in a variety of ensembles. On the other hand, I didn’t really like (or dislike, for that matter) much of what I played.

Then something shifted in my attitude. It began as I pondered a rather odd, hypothetical question that came to mind one rainy afternoon as I sat in my practice room:

“How would my playing change from this point onward if I knew nobody but ‘me’ would ever hear ‘me’ again?”

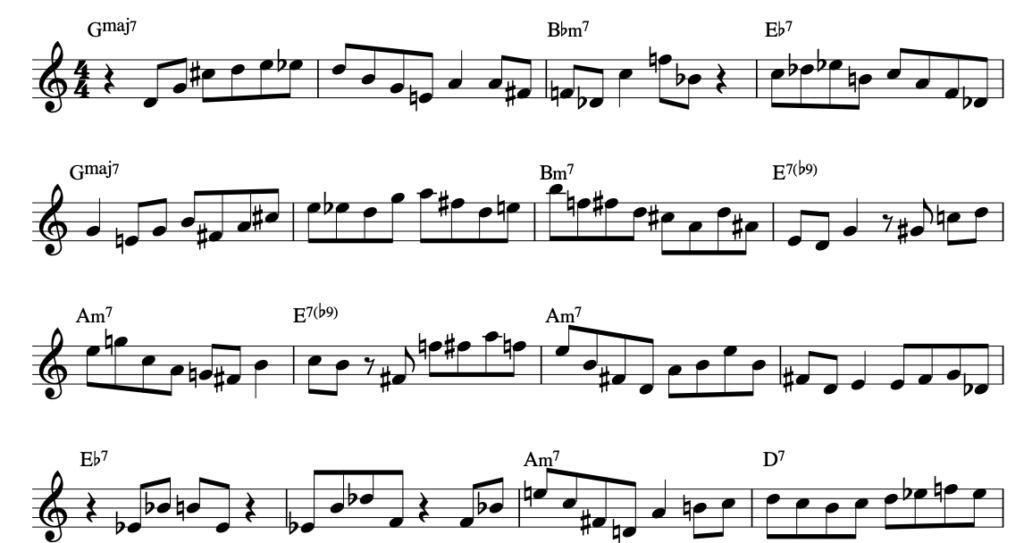

I spent a long time with this question, meditating on it daily for many weeks. I began to journal quite meticulously about my thoughts. Great details began to emerge in my journaling about my conception of sound, about aesthetics in improvisation (especially phrasing, and silence), about expanded sonic possibilities and techniques on saxophone, and more.

My imagination came to life! I became excited about how I was pondering this question, and was greatly inspired to practice in a completely new way.

To this day, I’m profoundly grateful for asking that question. Because that is the question I needed to ask in order to bring myself back to my original motivation to play music, those years ago. To bring myself back to the magic.

And it has been that “original motivation” that keeps me so endlessly engaged in my process as a musician, and in my growth as a human being.

In essence, what happened was a change in a basic question about assessing myself and my needs as a musician.

Instead of asking myself the question,

“Is this good?” (or “bad”, as the case may be), about anything that had to do with my playing, musical conception, etc.,

I began to ask myself instead,

“Is this what I want?”

Now, you might be thinking that these are the same thing. But the difference in how you might proceed, depending on which of these questions you ask yourself, can be huge.

And for sure there is overlap. A rich, flexible and resonant sound is a “good” thing, and it can also be “something I want”.

But when I go to “what I want” as a guideline, I turn to an intrinsic set of values to guide me toward a rich, flexible and resonant sound. I start thinking and imagining things more specifically, with great attention to detail.

A “rich, flexible and resonant” sound manifests itself in an enormous variety of colors and voices. And when it is my voice, my imagination…well, it just becomes clear and deeply satisfying to experience and to express.

You see, one of the potential drawbacks of the “good/bad” question is that it too typically comes from an extrinsic set of values, from things outside of the imagination and desire of the artist.

In my experience teaching the Alexander Technique to young, emerging performing artists (of a variety of disciplines), this assessment of “good” can sometimes come with a lack of clarity and details.

“I just recognize ‘good’ when I hear it”, is not a particularly constructive conception. Aimless and meandering, at best.

And the assessment of “bad” with these same artists is also too often lacking in useful information and details.

When I can help them to change the inquiry from “good/bad” to “want/don’t want”, they are able to seamlessly merge good technical qualities with authentic self expression. It’s win/win.

So give yourself a chance to think about these two questions. Explore them in the practice room with love and genuine curiosity. Keep them in mind when you’re listening to music you really love, too.

Allow yourself, as Thelonious Monk said, to “look like yourself”. This beautiful world we live in needs your voice.