A good percentage of musicians who seek my help as an Alexander Technique teacher do so because of chronic pain when playing their instruments.

And with some, it might not be because of pain, per se, but because of a palpable sense of strain and misdirected effort as they play.

Though the source of (and solution to) their problems vary, virtually all these musicians have one thing in common that is exacerbating their condition. Specifically, misconceptions about their human design in relation to making music on their instruments.

The thing that still amazes me after all these years of teaching, is that many of these misconceptions (that are causing some serious problems!) could so easily be remedied by taking the time to study and understand some very basic functional musculoskeletal anatomy and physiology.

Serious musicians give great attention to so many details of their craft and art. Sometimes obsessing over finding the best equipment, they also practice and study diligently and passionately, and are always on the lookout for anything to help them do what they do better.

Yet, as I’ve mentioned, far too many of them neglect to take the time to gain an accurate and detailed understanding of the workings of their most essential, primary instrument: themselves.

And that’s too bad. Because it is such a small, easily doable thing, really. In fact, sometimes just clarifying an anatomical reality is all it takes to solve a particular, debilitating problem.

Even spending a few hours studying and better understanding your design can make a significantly positive impact on how you practice and perform.

And if you teach, having this knowledge is not only essential, it is part and parcel of your responsibly to your students. They will have a far greater chance at success when you’re teaching them through the lens of anatomical and physiological accuracy.

So yes, understanding your human design is important. Very important.

The good new is that nowadays there are so many great, easily affordable and accessible resources to help you get the information you need.

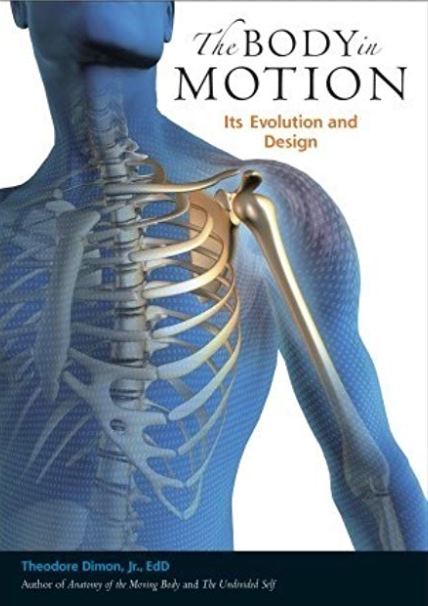

I recently came across what I think is perhaps the most essential book on understanding our human design as it relates to any kind of movement and activity (including playing music!)

It’s entitled The Body in Motion: Its Evolution and Design. Written by Alexander Technique teacher, Neurodyamics specialist and scholar, Theodore Dimon, Ed.D, it functions as both an in depth tutorial and reference for how we are designed to move.

The thing I like most about it is that each aspect of our anatomical structure is introduced and described relative to our evolutionary development, and in particular, our unique upright, bipedal design.

The book starts by laying the groundwork for the origins of animal movement, and how a system of muscles and bones came to be. Though this might sound like just an interesting (or not) story, it is much more than that.

By helping you understand how we evolved, based upon environmental need, the author is also helping you build a foundation in understanding how all our musculoskeletal structures work together as an interdependent whole. (This is very important, and can help you to avoid a good deal of dubious information floating about in this day and age of the internet.)

Dr. Dimon goes on to demonstrate and explain the most essential aspect of our ability to produce skilled movement: our upright support. It is this system of support and suspension that serves as the foundation for the complexity of all human movement.

From here, he elucidates upon the various structures essential to this movement: the spine, shoulder girdle, limbs, (including the hands), and then onto the mechanisms of breath and voice and more (including muscular spirals, etc.)

The text is clear and concise, and always introduces new ideas/concepts/chapters in relation to the previous ones, tying everything together under the central organizing principle of our unique, upright human design.

It is written with the layperson in mind, and if you’re new to musculoskeletal anatomy, you won’t be overwhelmed with a litany of scientific terminology. Just essential, practical information.

The book is also very nicely and abundantly illustrated by G. David Brown, so that whatever the author is presenting, is supported by visuals. Part of this visual support includes simplified drawings that demonstrate the mechanical principles of how bones and muscles work together. (This is immensely helpful!)

At only 107 pages, it’s a brief introduction into the most fundamental aspects of this wonderfully efficient design! You could probably read the entire book over a weekend. But the information you glean from it could positively impact you for the rest of your life. Highly recommended!