One of the things I emphasize when I’m coaching a musician is the importance of regularly redirecting thought whenever practicing or performing. It is this “redirecting” process that is an essential element of constructive change.

It is quite easy to fall into an autopilot frame of mind when spending any length of time with your instrument, letting yourself run on unconscious habit. Yet whenever this happens, you’re missing out on opportunities for improvement.

Each time you start a phrase, or even just begin to play a single note, you will have the greatest chance for success if you affirm and clarify two things in your consciousness:

- Intention

- Direction

Both of these are things that you wish for, things that you would like to have as you play.

Let’s start with intention. The way I define it, your intention is simply what you’d like to have happen musically.

Now, to be clear, intention has nothing to do directly with the mechanical aspects of executing the music, and has everything to do with how you imagine the music.

Your intention includes, but is not limited to:

- What you feel, what you’d like to express, what you’d like to communicate. It’s about the meaning of the music.

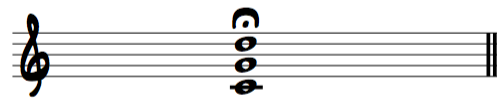

- How vividly you imagine your sound, including color, dynamics, articulation…even pitch.

- How your imagined expression will manifest itself in time (rhythmic clarity).

- The “bigger picture” of your imagined expression, the whole being greater than the sum of the parts.

- How this whole will interface with the other musicians (where applicable).

The more detailed your wish is for the musical expression, the more likely your brain will speak to your muscles in an effective way to carry the wish out. As one of my students (an outstanding professional French Horn player) says:

“Let the ear lead everything else.”

You’ll notice that I didn’t mention things like “embouchure”, “breath support”, “hand position”, “fingering”, etc. These things are not part of your musical intention. They are simply things that serve your intention. These are mechanical elements, not expressive ones.

Now, of course, it is fine to have some of these “mechanical” components in your thinking as you play. Just remember that they are not part of your musical intention. Rather, they are part of your overall direction.

Your intention is nested into your direction, but your direction is primarily about how you are going to carry out your intention. It’s about how you’re planning to coordinate your entire self to realize your imagined expression.

Your direction includes, but is not limited to:

- What you are doing with your head, neck, shoulders and back (letting them work together in an integrated, free way).

- How you are maintaining balance (and finding support and stability).

- The mobility of your joints (including your hips, knees and ankles).

- Your breathing (including the mobility and freedom of your ribs).

- What your eyes are doing (and your facial expression, in general).

- How you attend to the mechanical details as you express the music (fingering, support, embouchure, etc.)

Even the clearest of musical intentions won’t necessarily overcome a poorly directed, overly tense, and uncoordinated effort. To optimize your chance of success, you need to see to both. Intention and direction.

A key benefit of studying the Alexander Technique is in learning to improve how you use yourself in activity. It’s about learning to consciously and constructively direct your energy to most effectively serve your intentions.

The reason a good Alexander Technique teacher is so essential to this process, is that it is possible that you might be:

Unclear about the best, most efficient and effective way to use yourself. (Unfortunately, some of this could be a result of poorly prescribed pedagogy.)

Or,

Unconscious of the habits of use (movement, posture, reaction) that are interfering with your music making intentions.

(And of course, you might be challenged by a combination of both these issues.)

The aim of the Alexander Technique is to help you clearly understand how to use yourself in accordance with your design. By consciously subtracting habits of unnecessary tension, you learn to make music with greater ease, efficiency, clarity, consistency and satisfaction.

It’s about directing your efforts to help give you what you want.

As you become clearer and more detailed about your musical intentions, along with becoming more effective at directing your effort, you’ll find that you spend less conscious energy managing the specific mechanical details (what your tongue, fingers, etc. are doing) as you play.

You’ll learn to gradually trust that your brain knows quite well how to carry out your intentions, and does so best when you leave yourself alone enough for it to happen. This allows the music to flow from you more freely and expressively.

So next time you’re practicing, see if you can notice how clear you are with your intention and your direction. If you’re like a lot of reasonably skilled musicians, you might find that your intention is sometimes muddled by too many mechanical instructions (embouchure, air support, fingering, etc.), and that your direction does not include your entire self in a constructive way.

Notice how and where you create tension as you begin to play. Notice if/how you begin to take yourself out of balance. Notice where you begin to brace yourself. Notice where your attention goes. (Does it become narrow, inward and exclusive, or expansive, multi-directional and inclusive?) Then, consider how some of these things can impact the quality of your music making.

Notice how clear you are with the details of your intention. How vividly do you hear what you’re going to play before you play it? How clear are you about the meaning of the music? How clear are you about what you wish to communicate?

It takes time, curiosity, and persistent practice to effectively couple intention with direction in this way, but it is very much worth the effort.

Start each note, each phrase, each time you begin to play, with clear intention and constructive, inclusive direction, and you’re on your way to continued improvement and greater satisfaction.