Just as my practice goals and strategies evolve over time, so does my conception and implementation of warming up to practice.

Recently, one of the musicians that I coach asked me to elaborate more specifically how I’m currently warming up. So I thought I’d share my thoughts here with you all.

In the past few months, I’ve given myself a specific warmup project: playing one-octave modes from various scales (major, minor and harmonic major) legato, in slow sixteenth and thirty-second notes (half note equals 12 to 15) bpms).

I started out doing this as a way to challenge and improve my sense of what I call my “temporal imagination” (how vividly and accurately I perceive time and pulse). As I continue to work daily on this, the components (or objectives, if you will) of my daily warm-up have become distilled into the integration of these three things:

1. Optimal resonance

2. Perception of time

3. Psychophysical ease

Allow me to elaborate a bit on each of these components.

Optimal resonance

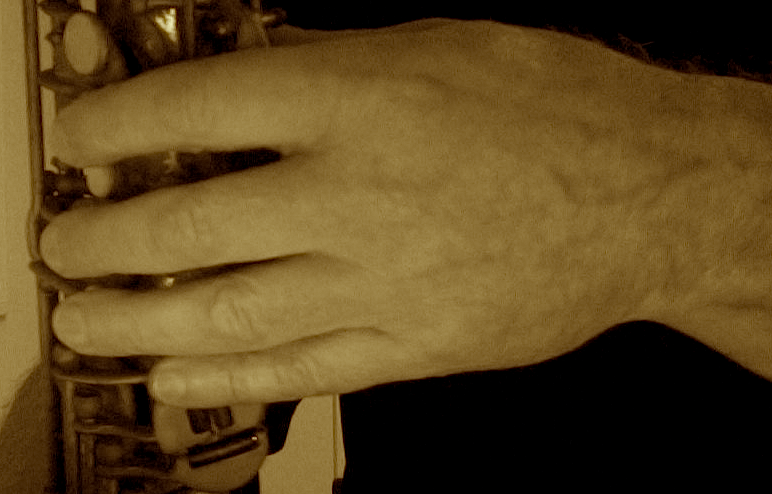

As a saxophonist, this has a very specific meaning to me. It involves finding the “balance” (or “exchange of energy”) between my air stream and my instrument. (Some of you saxophonists might notice that I simply said my “instrument” and not “the mouthpiece and reed”. I find this to be a more accurate description of the acoustic reality of the sound making process.)

In finding that balance, I’m looking for a consistently responsive and flexible breath support, coupled with an awareness/allowance for my voicing mechanisms (soft palate, tongue, jaw, nasal cavity, etc.) to “come alive”, so to speak.

I aim to feel the sound resonating gently inside my head (particularly, my nasal cavity), as I connect that feeling to the sensation of the sound inside my horn. I connect all of this immediately to how I hear my sound out into the room.

So I’m calling into play both internal and external sensory awareness and sensations.

Perception of time

My coordination, my technique, sound, expression…virtually everything I do is conditioned by my sense of time.

As I play each of these modes slowly with the metronome, my aim is to be present with each note.

What that means specifically is that I am connecting my “optimal resonance wish” with my internal perception of time, and how that internal perception of time relates to the reality of the metronome (an external cue for time) and my sound in the room.

When the metronome clicks so slowly, it becomes tempting to try to “play each note in time” by imagining how “evenly” each note should sound.

But as I try to play that way, I virtually always end up rushing just a bit. I tend to try to manage what my fingers are doing as opposed to truly listening and responding. It’s as if I’ve lost the sense of the wholeness of the phrase I’m playing.

So what I do instead is aim for optimum resonance on each as it moves in time to the next , while I hold in my imagination the anticipation of where the next click will fall on the metronome. This helps me integrate my internal consciousness (my intention and imagination) to the external world (hearing my sound; hearing the sound of the metronome).

Whenever I do this, my time instantly becomes lovely and easily precise. I can hear the evenness of not just every note that I play, but also the entire phrase as a whole.

Metaphrically, it’s as if I’m standing on top of a large mountain looking down on the whole valley. This is an immensely pleasurable experience, and it has significantly bolstered my confidence in my sense of time, as well as rhythm and meter.

Psychophysical ease

This is where my experience both teaching and learning (and applying) the Alexander Technique comes in handy. As I aim to integrate optimal resonance with my perception of time, I’m doing so through the foundation of a good “use” of my entire self.

(This is the central organizing principle of all my work as I warm up and practice.)

You might notice that I use the term “psychophysical ease” instead of “physical ease”. I do so because “psychophysical” is a more complete and accurate description of how we as human beings function in activity.

The “ease in my body” is incumbent upon my “ease and clarity in my thinking”. It is impossible to have one without the other.

So what I aim for as I’m connecting my optimal resonance to my perception of time, is finding the ease that is already there inside myself.

I notice my balanced connection to the floor through my feet, the mobility of my joints, the poise of my head on top of my spine (very important!) and the elastic quality of my ribs and torso as I breathe.

If I happen to notice something in my reaction (how I’m using myself) that I don’t want, I simply make a decision to stop doing it, and bring my attention gently back to the ease in my body, and the calm but alert clarity in my thinking, as I stay present with my sound and with the time.

As I mentioned above, my aim in warming up is to integrate these three components into one, singular, omnisensory experience. I’m never sacrificing one component at the expense of another.

The challenge in writing or talking about this , is that it sounds much more complicated, slow-moving and cumbersome than it actually is. In reality, my thoughts are quick, quiet and thorough. Powerefully effective in helping me to react optimally.

After my warm-up (which takes me about 10-15 minutes) I’m ready to work on anything (psychophysically ready!), and the rest of my practice session, virtually without fail, goes along constructively, efficiently and pleasurably.

So how do you warm up? What do you aim for specifically? What do you do to get yourself there? How do you know if/when you are “there”? If you’re not clear on the answer to these questions, I encourage you to investigate and experiment. (And please know that I’m here to help you if you need it.)