Don’t practice until you get it right. Practice it until you can’t get it wrong.

This saying is common among athletes as well as performing artists.

In essence, this sounds like a good reminder of how committed you must be, how faithfully and tenaciously you must practice something to do it consistently well. I’ve heard many accomplished musicians express some version of this sentiment when giving advice about practicing.

But in my experience as an Alexander Technique teacher, I’ve also seen a downside attached to this sentiment.

Let’s start with the upside.

Practicing with this kind of commitment can bring you deeply into the music. Spending long periods of time as you aim towards mastery, gives your brain a chance to more fully process the aural and motor components necessary to execute the music more readily.

Plus, holding yourself to higher standards is fundamental to improvement. It can fuel your path toward continued growth.

All good.

So where is the downside?

Well, let’s start with the fact that it is an impossibility.

No matter how much you practice any fine motor skill, there is no guarantee that you will never make a mistake carrying it out. Go to any concert of even the most virtuosic musicians, and, if you’re listening for it, you’ll hear what I sometimes euphemistically refer to as “unintended events” (more commonly referred to as “flaws”).

Besides, no matter how diligently you’ve prepared, no matter how hard you practice, there are things that are beyond your control: everything from weather conditions affecting your pitch, to unwanted physiologic responses, to mechanical issues with your instrument, to the unpredictability of other musicians. (I’m speaking mostly about performance as opposed to practice here.)

Perfection is a human construct. It is an ideal, not a universally quantifiable reality.

Unfortunately, the pursuit of absolute perfection tends to make many musicians frustrated, perpetually unsatisfied, and even somewhat resentful and fearful about practicing and performing.

Some of the students who seek my help are hamstrung by their impossible pursuit of perfection. They are nearly paralyzed as they play, holding themselves stiffly, their eyes intense and glaring, their breathing noisy and forced. They more closely resemble warriors than artists.

Their music-making lives are nearly devoid of any kind of love or joy. It is mostly about fear, demand and unreasonable expectation.

As they relentlessly practice the same thing over and over, day after day, they often lose touch with what they are actually doing with themselves as they pursue this tense kind of perfection.

This, unfortunately, leads to a variety of problems: chronic pain, injury, coordination issues, anxiety and more.

Another pitfall for some is that this “practice until I can’t get it wrong” work ethic can morph into a sort of mindlessness about performance and practice. It can tempt you to rely upon a mechanical and unconscious “auto pilot” to take care of everything.

This not only deprives you of the thrill of being in the moment as you play, but also, it can invite and cultivate habits of unnecessary tension (which can cause chronic pain and some of the other problems I mentioned above.)

It needn’t be this way.

A more practical and constructive saying might be something like:

Don’t practice until you get it right. Practice until you know it intimately.

(Yes, I know it’s not as catchy as the original, but it’s more doable. And it’s certainly more healthy.)

Knowing something intimately doesn’t mean you’re beyond making errors. It means that you can always find your way back if and when you do. You can self-correct. You can stay present. You can stay connected with your muse, your desire and the overall meaning of the music. You become responsive, inspired. In the moment.

How do you know when you know the music intimately?

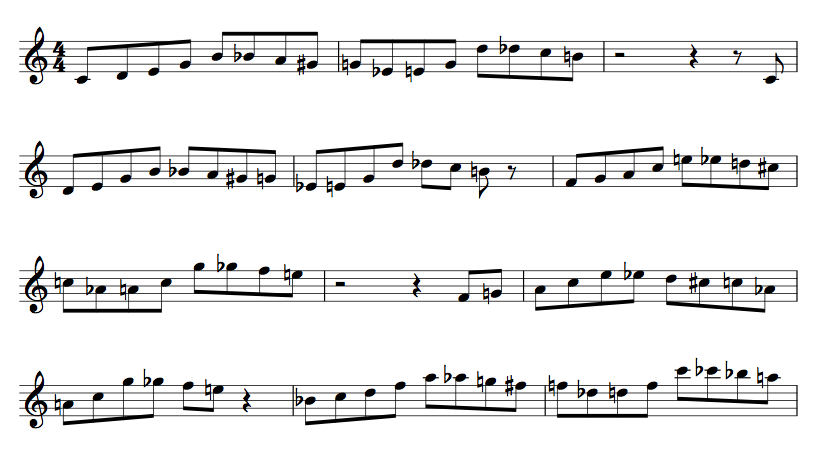

It starts with your ear. Can you sing it with reasonably detailed accuracy? If you can sing it, it’s deeply wired in your brain (your ear, your imagination). If you get off track, it’s easy to quickly find your way back.

Second, make sure you are crystal clear about any technical choices that best support the music: Fingerings, voicing, articulations, breathing, dynamics. Take time and be mindful with these choices. As you sing the music, review in your mind these details of technique. Merge technique and imagination seamlessly together, and let your desires be clear and lucid in detail.

Finally (as I’ve mentioned above, as well as in several of my other articles) create your music from a place of love and desire. Love cultivates the best kind of intimacy. Aim high, remain flexible, be present and enjoy the unknown mystery and magic of playing music.