After recently reading some rather disheartening discussions on various social media platforms, where professional musicians were discussing the “inevitability” of chronic pain and injuries, I thought I’d offer some (hopefully) helpful thoughts.

As a certified Alexander Technique teacher and musical practice coach, I have a good amount of experience helping musicians effectively address such issues. I’d like to offer up what I think are the three most important steps you can take if you’re struggling with chronic pain associated with playing your instrument.

Step One: Believe that you can improve.

This is one of the most commonly counterproductive assumptions many musicians I encounter have about discomfort, chronic pain and chronic injuries associate with making music.

Chronic pain conditions associated with a repetitive activity like playing a musical instrument are typically caused because of the interplay between two things:

Overuse, and misuse.

You can dramatically improve upon both of these variables. It’s a matter of choice. And that choice starts with belief. If you believe you can’t improve upon these things, then you’re right. But only because your disbelief stops you from taking action.

So start by believing things can get better. (Because they most certainly can!)

Step Two: Do some research.

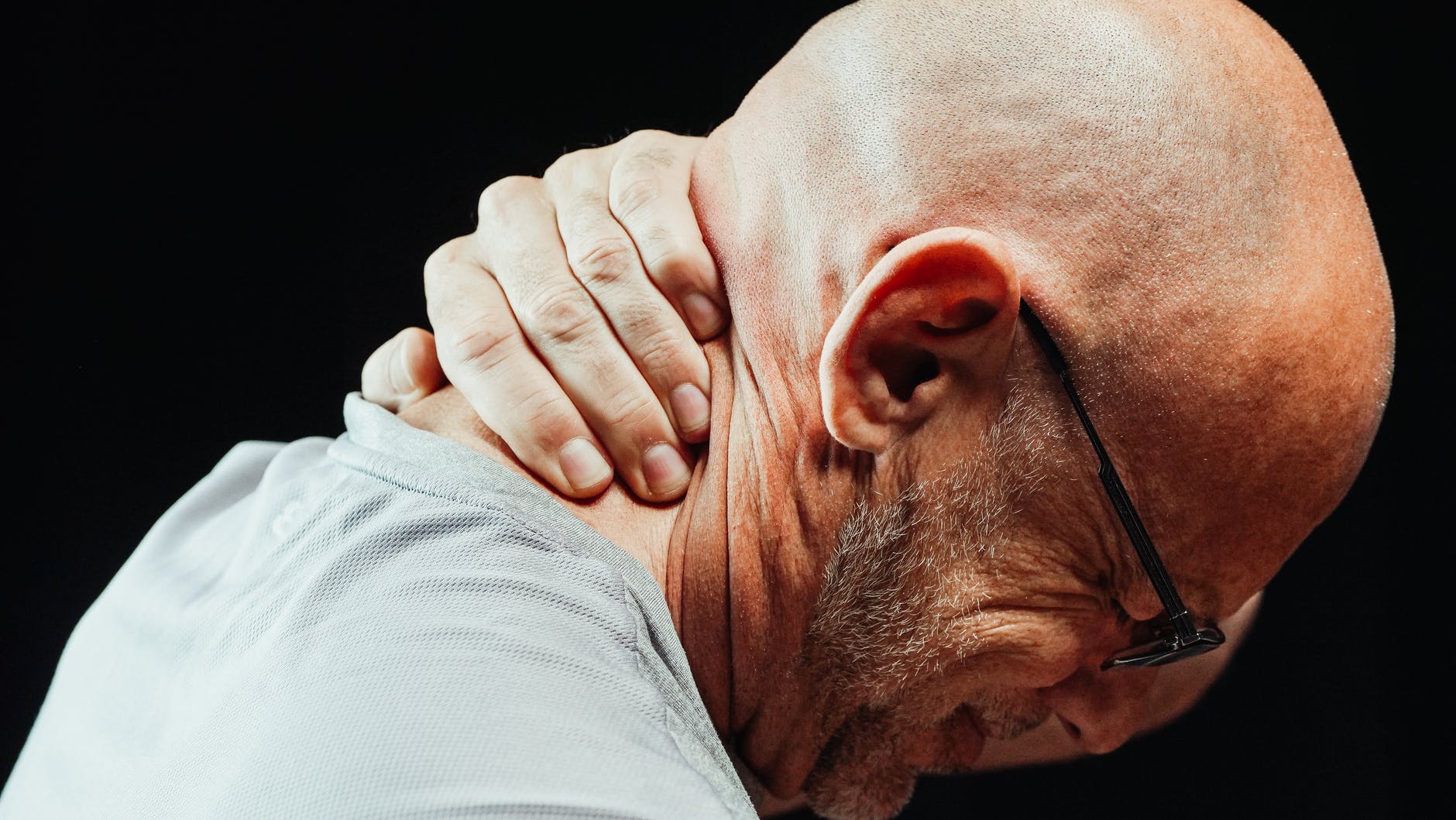

If you’re at any stage of chronic pain or discomfort, take some time to research and understand the science behind your struggle. Try to find simple, but relevant information on the physiological framework that defines your condition.

This starts with getting a medical diagnosis from your primary care physician. Your condition might not be one that can be effectively addressed from a medical point of view, but it is always a good place to start. Even if you can’t get a definitive diagnosis for your condition, you should at least make sure that it’s not because of a measurably pathological element (e.g. neurological, metabolic, etc.) that truly needs immediate medical attention.

From there, you can do some extra research on your own.

For example, if it appears you might have the beginning of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, first understand (from an anatomical and physiological perspective) what the carpal tunnel actually is, and what you might be doing in your movements to cause the inflammation that leads to the Syndrome.

The better you understand the “mechanical principle” of what is causing the dysfunction, the better equipped you are to choice the best course of action to improve.

And part of that course of action involves finding the appropriate professional help, if needed. So take time to understand the “scope of practice” that various practitioners adhere to, and decide which practitioner(s) might be able to help.

There are many professional resources these days to effectively address even the most stubborn chronic pain issues. Skilled movement experts (like Alexander Technique, and other somatic education teachers, physical therapists, etc.) and skilled manual therapists (like neuromuscular massage therapists, chiropractors, etc.) are plentiful.

Then it’s time to do some research to find the specific individual(s) best suited to help you. Look for recommendations from others. Read reviews. Ask questions.

Also, take some time to research the potential “environmental” factors (e.g., equipment, lighting, chairs, stands, props/supports, etc.) that can impact your condition.

Three: Take action

Once you’ve done your research, it’s time to go into action. Get an initial consultation with the appropriate professional(s). Make the specific environmental changes you’ve researched that seem to be most likely to impact you in a positive way.

After you’ve taken some action, make a conscious decision to reassess your choices. Give things a reasonable time to make an impact (sometimes changing these things takes a fair amount of time and patience), but be willing to recognize when something clearly isn’t working.

And if it isn’t working, do some more research. Ask more questions. Find another way.

Pain can be a slippery slope, in that the experience of pain is impacted by many variables. And there certainly are specific chronic conditions that seem to be impervious to any kind of help.

But most chronic pain and injury is most definitely improvable. Often significantly so.

Just remember the most important step in this process (step one). Believe that things can get better…