Pulse, rhythm, meter and feel. These are the essential components of time that musicians utilize to create music.

I’ve been nearly obsessed with exploring and better understanding how our perception of time impacts our music (including going deep into the science of how our brains perceive time). Even our most basic movement skills are coordinated through our sense of time.

Without time, there is no coordinated movement. None. And without coordinated movement, there is no music.

In every practice session I’m working on things that challenge and expand my sense of time. Again: pulse, rhythm, meter and feel. (I’ve even composed two eBooks with exercises in polymeter and multiple time subdivisions that document some of my explorations.)

One of the “staples” of my work with time is using multiple, simultaneous pulses; i.e., working with more than one tempo at a time (no pun intended). I usually do this either with metronomes and/or with drum grooves (I really like the Smartphone app Drum Genius for this!)

I’ve been working this way for several years now, and I continue to reap wonderful benefits from my efforts. If you haven’t practiced with multiple time sources, I highly recommend that you do so. Here’s why:

The three most palpable skills that you will cultivate from practicing with multiple tempos are:

1 Improved “precision” in your perception of pulse (steadier, more reliable sense of time)

2 Improved flexibility and adaptability in changing tempos (finding the “groove” more immediately and solidly; not getting “stuck” in certain tempo ranges)

3 The ability to actively and accurately “imagine” tempos nested within tempos (this is especially useful for improvising musicians!)

As you work this way you will also find that your technique becomes cleaner and more precise as well (though without losing the musical flexibility that is so important to expressive and dynamic playing).

Here’s a simple way to get started:

Begin by using two metronomes that have slightly different sounding clicks (this makes it easier for you to perceive of and integrate the two pulses).

Set one metronome at half notes, around 60 bpm. Set the second metronome at 2/3 the tempo of the first. So in this case, half notes at 40 bpm.

Find a simple scale or melodic pattern to practice, composed of quarters and/or eighth notes (again something simple). Start at the faster tempo and play the pattern a few times to embody the tempo as you “notice” the click of the slower metronome.

At a certain point, jump over to the slower metronome and play the same pattern at the slower tempo. Aim for embodying the new tempo as soon as possible. Once you feel that you’ve locked in the new tempo, switch back to the original tempo, and so on, moving back and forth between tempos.

Whichever tempo you are in, see that you are “hearing” (but not necessarily “listening to” the other metronome clicks).

The aim here at first is not so much being able to conceive of both tempos simultaneously, but rather that you can easily and readily switch between tempos.

Once you’re comfortable with all these activities, add another challenge. Perhaps it is to play a particular piece (etude, solo transcription, etc.) as you move back and forth between tempos. Or you can also add more rythmic complexity the original scale pattern you started with, using triplets, quintuplets, syncopation, etc.

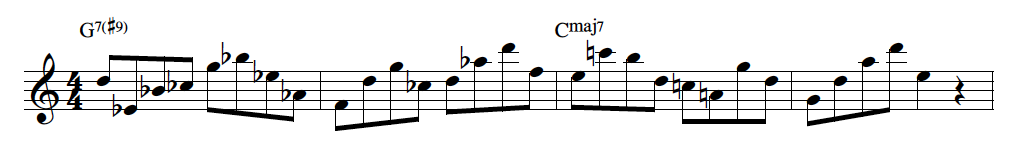

If you’re an improviser, the next challenge could be improvising with the two metronomes. First, just improvise over a mode, scale, or simple riff, something devoid of a specific time/harmonic form. Once you feel solid doing that, improvise over a short, familiar harmonic form (maybe the blues?) And so on, again, adjusting the time/harmonic form to fit the new tempo.

When you get to the point where you’re able to function well in these two tempos, decrease the differences in time between the two metronomes. Maybe set one at half note at 60 and the other at half note at 45. You can continue to lessen the tempo differences until you get both metronomes at nearly similar tempos (say 60 bpm at one and 55 bpm at the other).

At whatever two tempos you’re working with, take some time to sit and listen (without playing) to how the two tempos eventually converge and make a singular, simultaneous click. Try to conceive of and anticipate this occurrence. Find the pattern.

And of course, you can also play around with different drum loops, perhaps exploring not only multiple times, but multiple feels and metered subdivision. For example I like working with the metronome clicking on half notes, while I add a drum groove in 4/4 that is subdivided into four, 3/4 patterns (12 beats over three measures).

If you’re truly brave and adventurous, you can add a third (or more?) time source.

If you continue to work this way, you will learn (as I have) to actually “hear and imagine” more than one tempo and subdivision simultaneously. As I’ve stated above this will not only make you a “stronger” musician (better reader, time keeper, etc.), but will open up amazing roads as an improviser, allowing you to create an abundance of rhythmic tension and release.

So give it a try. Have fun with it! Explore, learn. And grow as you do so!