There really is no such thing as truly hearing the “absolute reality” of your sound as you play. In part, that’s because your sound constantly changes as it is impacted by two fundamental things:

1. Environment

2. Perception

Environment has to do with such things as the acoustical qualities of the room you’re playing in, coupled with other variables, such as the other instruments you’re playing with.

Perception has to do with how you hear your sound.

More specifically, it has to do with how you pay attention to your sound as you play. Your perception includes not only the environment in which you are playing, but also how you’re sensing the bony structures inside your head (and close to your ears!) as they vibrate in response to your playing.

Your perception of your sound both shapes the sound itself and influences your experience of it. Perception and experience being inextricably connected. (If you’ve ever played in a particularly good or particularly horrible acoustical setting, you’ve probably realized this.)

Whenever I teach the Alexander Technique to musicians, we do lots of explorations with how they hear their sounds, and how that perception influences their coordination. This is often a question not just of “how” they’re listening for their sound, but also “where” they’re listening for it.

If I’m working with a musician who has serious problems with loss of skill (focal dystonia, for example), I find without fail that the musician in question is listening to his/her sound in a very inflexible, internally focused way.

More specifically, the sound is being felt (kinesthetically) almost more than it is actually being heard in the external environment.

An overly internal focus of attention is often the very thing that leads these musicians to seek my help. This quality of attention tends to exclude and divide, as opposed to include and integrate.

The motor mechanisms of the brain don’t work optimally this way, and problems with tone quality, attack, time, articulation and technical control can arise as a result of such thinking.

Striking a healthy, dynamic balance between the internal (what’s going on inside of you) and external (what’s going on outside of you) helps support optimal coordination and skill.

One of the tools I use to help musicians find this balance involves a very simple experiment with sound and perception. And even for musicians who don’t have any discernible problems, this little experiment can be eye-opening, and quite helpful. Here it is:

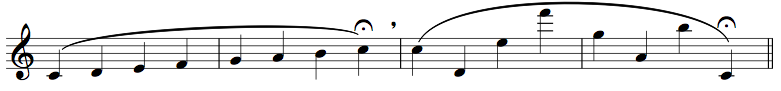

Choose something lyrical and highly familiar and enjoyable for you to play.

Then, play the piece (or passage, or whatever) as you make a conscious decision to hear your sound as close to you as you possibly can.

So if you’re a wind instrumentalist or a singer, you’ll listen for the sound right inside your head: in your oral cavity, nasal passages, etc. If you play a string instrument, you’ll listen for the sound right where your bow or fingers make contact with the strings.

Play like this a couple of times, until you’re reasonably sure that you carried out your intention to hear your sound so closely.

Now, play the same piece, this time bringing your attention to the room itself. Listen for your sound to the very far corners of the room (no matter how large or small).

What do you notice?

Is there a contrast between one quality of attention and the other in terms of how you experience your sound? (quality, color, volume, resonance, control)

Is there a difference in your effort? (more tension, less tension, better coordination, worse coordination?)

Play the piece yet again, this time bringing most of your attention to the feel of the sound inside the instrument itself (not in your body!) Take this attention to the feel of the sound in the instrument and with it, listen for your sound out into the far corners of the room.

How does this compare/contrast to the other two ways of paying attention? Which seems to help you most?

After experimenting this way a few times, giving yourself a chance to process and reflect upon the experiences, try doing all three experiments with some kind of recording device.

Do you notice anything different in your sound as you change your thinking? Resonance, volume, color, pitch? If you notice any differences, keep in mind that you’re noticing how your perception of your sound impacts its quality. (This reality can be very powerful, and working in accordance with it can be highly practical!)

You can also explore going back and forth from hearing the sound near you, and farther away all in the same piece (even in the same phrase).

So how do you typically listen to your sound as you play? Close to you? Away from you? (Somewhere in between?) Do you listen to yourself differently depending on the environment? The needs of the situation itself?

By becoming aware of how/where you listen to yourself, you can give yourself the opportunity to improve both your sound and your overall skill as you play.

Explore this process. See what you like. What seems to help most. What allows you to respond with the greatest availability and precision. Realize that, ultimately, your thinking can (and should) remain flexible and responsive, and generally be as outward oriented as is practically possible.

Take these “tools of thinking” into your practice, rehearsal and performance, honing your attention to best serve your intention and your expression.

Thank you Bill, I will definitely dig into this. Frankly, this is a concept I’ve never even considered. When playing, or practicing long tones for example, I tend to shift my focus from the collective overall “sound,” and when I really focus in, I try to listen out for the different components of the sound; the core and whether its focused or diffuse, still or wavering, that drone-like “edge” of the sound, the higher partials whistling or chiming like Chinese bells in the skull. But it’s never occurred to me to try and focus on these things and what they’re doing inside, or out in the room, the atmosphere, so on and so forth. Very interesting.

Thank you!

-Nathan

Glad to know this gave you something to think about and explore, Nathan. Connecting the internal and external components brings deep intention to your playing. Have fun discovering new things!