One of the staples of practicing a wind instrument or a string instrument is holding sustained tones. The initial aim of practicing “long tones” is to improve sound, intonation and (for some musicians) endurance.

Yet I’m still taken aback at the amount of musicians I encounter who view long tone practice as a mindless activity that “builds strength”. A necessary evil, of sorts, that is part of the obligatory price of admission to the more interesting parts of the practice session.

It’s not unusual for me, when coaching brass instrumentalists, for example, to find out that they often regularly practices long tones while watching television, or engaging in some other kind distracting activity.

I find that unfortunate.

This kind of mindless practice, at the very best, helps these musicians maintain a certain amount of endurance (and so-called “muscle memory), but not much else.

At the worst it acts as a breeding ground for cultivating unnecessary and unwanted habits of tension. In my teaching experience, a good amount of repetitive strain injuries for wind instrumentalists can attributed, in no small part, to this kind of practice.

But even if no physical problems arise from practicing this way, there is so much that musicians are missing out on by not taking a more conscious approach to this tried and true practice activity.

The ultimate value of practicing long tones is in giving you a chance to develop a more intimate experience with the most intimate, personal component of your musical expression: Your sound.

One of my Alexander Technique students, himself an excellent Horn player, describes his long tone work as sound meditation.

I like that description a lot. It resonates with the way I approach long tones. (I actually look forward to this part of my daily routine with great relish!)

Sound meditation. What that means is that each time you practice a long tone there are at least two things in place before the note even starts:

- A crystal clear and detailed aural conception of how you want the note to sound.

- Attention to how you can best use yourself to get the sound you want.

Allow me to elaborate on these two things.

First, your conception. Your sound starts “between your ears”, in your imagination. When you are clear about the details of how you want something to sound, your brain has the best chance of carrying out your wishes. In holding long tones, some of the details of your sound are: attack, color, pitch, dynamic, spread (and center), vibrato, shading, release, etc.

Lots of details.

If you spend time being conscious of these details, they will show up more readily (and more naturally) when you actually play music. They become a seamless extension of your self-expression as a musician.

Now you’ll of course notice that various components of your own playing mechanism (e.g., your lips, soft palate, tongue, jaw, respiratory muscles, etc.) have to come into play a certain way to get the sound qualities you want.

One of the aims of long tones should be for you be conscious of how these mechanical components work together, but not to get stuck putting too much of your attention on them. Once you get what you want by “directing your mechanism”, bring your attention to the sound itself and allow the mechanism to follow your wishes. Let your imagination lead your coordination.

In other words, wish for a “round, dark sound”, not for your “jaw to come forward” as you go after that sound. As you practice this way, you also learn to more vividly “feel” your sound inside the instrument as you hear it outside in the room.

Now let’s look at your use. When I’m talking about your use, I’m not just talking about the mechanism that is mostly responsible for producing your sound. I’m talking about what you are doing with your entire self as you produce your sound.

As you start your sound:

Do you stiffen your neck, maybe compressing your head down onto your spine? Do you arch your back? Pull your shoulders down? Lock your knees? Pull your feet off the floor? Stiffen your arms (and hands)? Knit your brow tightly? Gasp in loudly to take a breath?

(I could go on naming these unnecessary habits of tense reaction…)

Part of your long tone practice should be about improving not only how you are using yourself, but also about developing and improving upon your ability to constructively pay attention to yourself as you play.

Again, if you work towards this kind of inclusive attention, it becomes a natural part of your technique and expression as a musician.

So start by making a decision to make your long tone practice a real sound meditation. Turn off the television. Rid yourself of distractions. Discover more and more details and subtleties about your sound. Find intimacy with your sound. Discover pleasure in doing so.

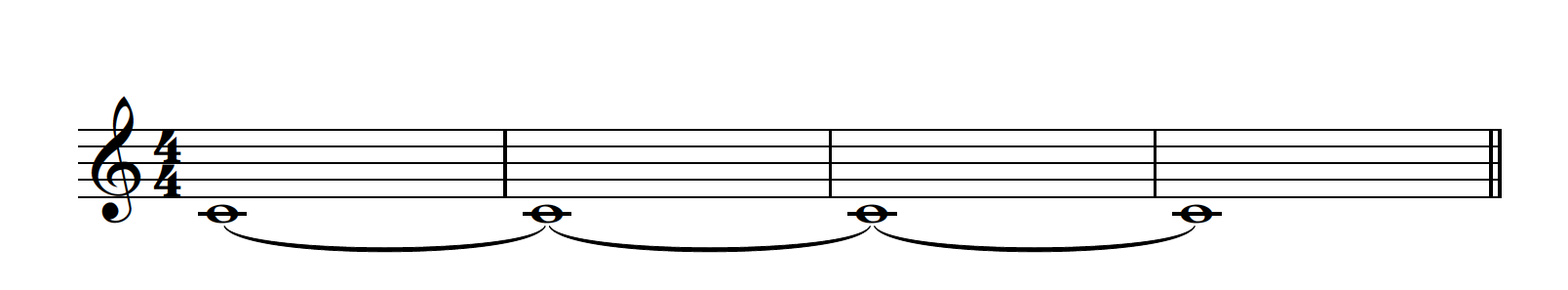

It doesn’t matter if you’re playing dynamically static single sustained tones, or if you’re working with crescendo and diminuendo, or if you’re playing slowly moving melodies with an expressive vibrato.

As long as you bring consciousness and clearer intention to what you do, you’ll not only play with less effort, but with greater depth of expression and enjoyment.