Jazz writer Whitney Balliet famously called jazz, “the sound of surprise”. It is this thrill of unpredictable, yet cogent, musical communication that is the essence of jazz (and many other genres of improvised music, too!)

And to this day, there are those artists who are still consistently able to surprise us each time they play.

What makes their playing so surprising to us?

Well, many things of course.

But from moment to moment, the main thing that keeps us on the edge of our seats as we listen to a masterful solo unfold is the soloist’s use of rhythm.

Rhythm is a huge topic. It is vast and endless; there could never be such thing as a comprehensive “rhythmic thesaurus”.

Rhythm is also at the heart of our spoken language. Every language has a distinctive use of rhythm to nuance and emphasize meaning.

Yet rhythm is too often the most neglected sub-discipline within the larger discipline of jazz improvisation.

Don’t get me wrong. There are many exciting ways to use melodic sequence and harmonic substitution when improvising over chord changes.

But listen to even the most adventurously harmonic jazz musician express these harmonically novel musings with nothing but an unending stream of eighth notes, chorus after chorus, and the novelty soon wears thin.

It simply becomes predictable.

To stay adventurous, spontaneous, flexibly expressive, exciting and wonderfully unpredictable, you’d be wise to devote a serious amount of time exclusively to rhythmic study.

In playing and studying jazz, rhythm actually encompasses these four things:

- Feel (including articulation)

- Rhythmic content (whichever rhythms you’re using at any given instant)

- Space (the silence that is in contrast to the sounds you create, which becomes part of your “phrasing”)

- Subdivision (how your choice of rhythmic content and space are used to imply meter, also another component of your phrasing)

Most moderately skilled jazz improvisers already have a good use of feel: clear, solid articulation and time feel (it swings!), all wrapped within an expressive sound. It is obvious that some conscious effort has been spent developing this very important component of skill.

Yet it is still confounding to me that so many of these same musicians seem so underdeveloped with their skill in using the other three things I’ve mentioned:

Rhythmic content is often 95% eighth, sixteenth and quarter notes/rests. Polyrhythms (with the exception of the ubiquitous eighth-note triplets) rarely, if ever, appear, other than by pure accident. Quintuplets, septuplets (both which can be used to great effect to create tension against a swing feel) are virtually non-existent.

The consciousness of space (silence) in creating a solo is often lacking to a point where it is considered novel when used to great effect. (I’m thinking of Miles Davis’ playing here.)

The other thing that makes a solo sound highly predictable (besides a highly homogenous rhythmic content) is subdivision. Just because a composition is in 4/4, and the chord changes fit nicely within the 4/4 form, doesn’t mean you have to play everything as if it were emphasizing both the time signature and the form. If you listen to Lester Young (his solo on Lady Be Good is a great example), you’ll hear how he shifts the meter within the form, sometimes implying 5/4 and 3/4. This use of polymeter not only adds to the swing feel, it also keeps the listener in an engaged state of surprise.

So what can you do to make your playing more exciting, more spontaneous, and less predictable? Well, you can’t go wrong by devoting lots of time to developing your rhythmic conception and skills. For starters, become more conscious of the four skills I’ve mentioned above. Then, get to work.

Here are some specific things you can do:

- Expand your time feel-Even if all you like to do is swing, there are so many different ways to do this. Listen to how differently Art Farmer plays eighth notes in contrast with Coleman Hawkins. As an exercise, try to imitate both. Then explore different ways to swing the eight notes when you improvise.

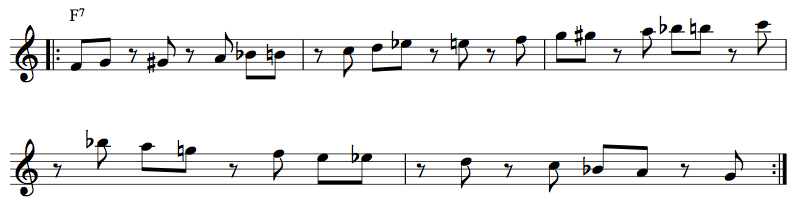

- Study polyrhythm-There are so many great resources available to increase your rhythmic vocabulary these days. I’ve written an e-book that I think serves as a simple, yet highly practical method to feel/imagine/hear triplets, quintuplets, septuplets and their syncopated subdivisions. Also, when you do learn new melodic patterns/sequences, make a point of doing them with a wide variety of rhythms, not just as a slew of continuous eighth or sixteenth notes. Use your imagination.

- Listen (and study) outside of your discipline-I studied Balkan music some time back (lots of odd meters, like 7/8, 11/8, etc.), which significantly expanded my rhythmic conception and skill in playing jazz. Find a kind of music you like that is rhythmically exotic and unfamiliar. Listen, study, analyze and apply.

- Explore silence-Practice improvising over a song form as you consciously let lots of time go by between phrases. It’s harder than it sounds at first, and will probably seem unnatural and awkward. But if you persist, you’ll find that you “hear” silence just as clearly as you hear sound. This will profoundly change the way you improvise. I could (and just might!) write an entire blog article about how best to approach this topic alone.

- Study polymeter-Learning to hear odd-metered subdivisions within even-metered song forms opens up an entire new universe of phrasing possibilities to you. (I’ve also composed another e-book that methodically addresses this discipline specifically for the jazz musician.)

You’ll rarely play beyond what you can imagine and what you’ve practiced. By making the study of rhythm a daily, conscious (and conscientious!) discipline, you’ll keep your listeners (and band mates) more consistently and joyfully surprised and engaged in what you do.

And speaking of the “sound of surprise”, I’ll leave you with this masterpiece of rhythmic/thematic development by the great, always unpredictable, Sonny Rollins. Enjoy!