I once heard the following exchange between two jazz musicians talking about one of their colleagues:

“He has great ears. He can play anything he hears”, asserts the first musician.

“Yes, that’s true. Unfortunately, he just doesn’t hear that much”, responds the second.

Ultimately, all artistic expression through music involves playing by ear. This is true whether you’re an improviser or an interpretive musician.

If you’re an interpretive musician, you’re vividly imagining (internally hearing) the details and quality of each phrase as you play. This is, in large part, what your practice process has been about.

If you’re improvising, you’re creating music instantaneously, trusting your muse as you follow your ear and intuition. Much of your practice has been about helping you to immediately access what you hear (imagine) as you improvise.

Part of this “hearing” most likely includes connecting a cognitive understanding (harmony, form, structure, etc.) with the aural impressions that these particular musical elements produce.

We’ve all heard improvising that sounds a bit too much like “thinking” and not enough like “hearing” (perhaps we’ve all been there, too, from time to time; I know I have). And it’s no mystery that the greatest improvisers also have (or had) wonderfully developed ears.

Tenor Saxophonist Joe Henderson is an example of somebody whose ears were so highly developed, that he could immediately play back virtually anything he heard (including his own inner musical voice!)

You won’t find a single teacher of jazz pedagogy who doesn’t emphasize the importance of continuously cultivating aural skills. It’s simply essential to improvising effectively, expressively and authentically.

There are two inextricably related ingredients necessary for “growing” your ears. I label them as follows:

1. Processing

2. Feeding

Processing

Processing is identifying what you can already imagine (which interval, scale, chord quality, melodic pattern, etc.) It has an active component and a passive one:

The passive component is your ability to recognize and label what you hear after hearing it (perfect 5th, C melodic minor scale, 1, 3, 5, 6 pattern, etc.)

The active component is your ability to reproduce what you hear, through your voice and/or through your instrument.

Singing is at the heart of this skill. If you can’t sing something, you’re not quite hearing it completely and clearly, and you’ll have a difficult time finding it on your instrument.

On the other hand, if you are able to sing something with pinpoint accuracy, you can find it on your instrument rather quickly and easily.

In a sense, the ultimate aim of this skill is to place intuition in front of intellect. Specifically, you can find and reproduce the pitches you’re hearing even before you can cognitively determine what pitches they are (no time to do this when you’re actually improvising).

Both the active and the passive components of processing are crucial to a well-developed ear.

Having said that, there is often a tendency in ear training study to put more of an emphasis on identification than on reproduction.

I’ve encountered students of improvisation who can easily identify intervals, modes, chord qualities and tensions, yet can’t even sing a simple diminished scale pattern over a dominant 7th chord. This student clearly needs more work with active processing.

Or the student may be able to find sounds (key centers, chord qualities, licks, etc.) fairly easily with the help of his/her instrument, but can’t sing them back readily. More singing and less playing is needed in the practice room to improve in this area.

Until you can sing something back, you don’t have it fully internalized. It never becomes deeply ingrained your aural imagination. (It never becomes fully processed.)

And even if you still can use it in improvising, it comes more from thinking than from intuition, thus lessening and interferring with some of your subconscious spontaneity.

On the flip side, you might be able to sing and play back whatever you hear fairly easily, but can’t cognitively identify it. There have been several jazz greats who had no knowledge of the theoretical aspects of harmony (the great trumpeter, Chet Baker is an example).

I, for one, certainly believe you can be a very effective improviser without being cognizant of the structural (theoretical) elements involved in improvisation. (Just listen to Chet Baker!)

Yet improving your theoretical knowledge/understanding and tying that into your ears can open up lots of other possibilities. This brings us to the other ingredient for growing your ears:

Feeding

Feeding is the act of giving yourself more to imagine. In large part it involves using your intellect to challenge and expand (to feed) what you are currently capable of hearing, imagining and recognizing…going beyond the conventional and familiar, towards the novel.

This means finding new ways to approach and organize the materials of music: new harmonic concepts/relationships, unconventional intervallic movements/patterns, polymeter (and other kinds asymmetrical phrasing), etc.

In essence, you have to actively search for things to feed your ears. Where? Here are five good places to start:

1. Transcribing-Just about anytime you transcribe a great improvised solo, you’re not only improving your processing skills, but you’re also feeding your ears. If you’ve transcribed a lot, aim for players that are far from the mainstream (or far from what you’re familiar with), and who have a very personal, unique and appealing improvisational language.

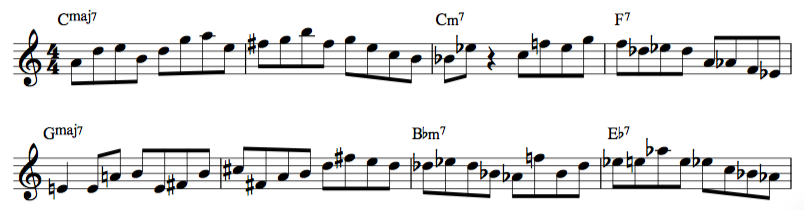

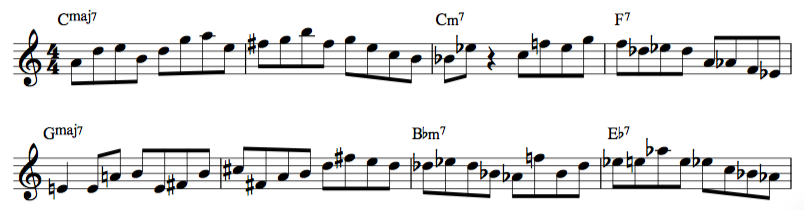

2. Improvisational etudes-Either writing them yourself, or playing and studying from some of the many great resources available these days can really open up your ears and your thinking. I’ve written my own etude books with the specific purpose of feeding my ears.

3. Improvisers from other genres-If you’re a jazz player, find a great improviser from another genre, and spend lots of time listening, singing, analyzing (and perhaps even transcribing).

4. Non-improvised music-I learned so much about my own improvisational language from listening to and studying the music of Béla Bartók. Any kind of “strange and compelling” music (how I first identified Bartók) can be used to feed your ears.

5. Reflection-Ultimately, you sit with the materials of music and use your intellect and curiosity (“What would it sound like if….?” ) to think of new ways to create melodic movement. Finding new ways to make harmonic relationships over familiar forms, new ways to organize melodies and shapes, new ways to conceive of time, rhythm and form, can be a lifelong endeavor. It is one that will continuously reward you, enabling you to establish and grow your own personal improvisational language.

And of course, all this feeding involves processing. When all is said and done, you’re still figuring out, internalizing, and reproducing what you are hearing.

So if you want to improvise more intuitively, personally, consistently and expressively, stay vigilant about growing your ears: identify, understand, sing, think, challenge, imagine, and above all, listen.