Some months ago I wrote an article about how coordination was inextricably linked to the perception of time and rhythm. But just recently, I realized another aspect of this connection while giving an Alexander Technique lesson to a bassist.

This student could not seem to play a particular technical passage beyond a specific tempo without the entire passage falling completely apart. I began to suspect that he was thinking about the tempo in such a way as to create problems for himself as he played.

As it turned out, his self-imposed obstacle wasn’t a lack of clarity of tempo (he wasn’t dragging or slowing), nor of rhythmic conception (he demonstrated to me that he could sing the rhythms of this passage quite accurately).

Instead, it was his subjective reaction to what he defined as a “fast” tempo.

I discovered this after asking him a few things about how he was thinking:

“Why does it always seem to fall apart there?”, I asked.

“I’m not sure. It’s actually quite easy to play at a slower tempo. It just seems to get tricky when I try to play it at a fast tempo.”, he replied.

“What is a fast tempo?” I further enquired.

“When I’m practicing at home, it seems like it gets fast at about quarter note equals 138.”, he responded.

So I broke out the metronome. And sure enough, he was fine until that “breaking point” of 138. Then I had him play it at 132 and everything was fine: accurate, beautiful, lively, clear. I asked him his perception.

“No problems. Like I said, it’s not difficult to play at slower tempos. And I thought to myself, “132 isn’t that much slower than 138.” But what I observed as he played at this slightly slower tempo helped shed light on the real problem.

The most significant thing I noticed as he played it at this “easier” tempo was how differently he was using himself as he played. His eyes looked calm, yet lively. His neck and shoulders looked more spacious and elastic. He looked more mobile and fluid, less “planted” and rigid. In Alexander Techique slang, we’d say that he was using his primary control (head/neck/back) in a more constructive, helpful way.

I had him notice how free and easy he was as he played. (Being a good Alexander student, he could notice this quite readily.)

Then we brought the tempo back up to 138. And everything changed.

His eyes became fixed, almost fierce looking as he knitted his brow. His shoulders began to narrow as his neck stiffened slightly. I asked him to notice this. (Again, being the good Alexander student that he was, he could do so readily.)

“Why do you think you change how you’re using yourself so noticeably?”, I asked.

His reply: “Because now I think I’m playing fast. And the thought of playing fast seems to tempt me to do certain things.” He just solved the mystery.

So we began to work toward getting him to react differently to the thought of playing “fast” in this particular passage.

The first thing he did was to redirect his thinking as he played in such a way as to prevent himself from physically responding in his “fast tempo” habitual way (no tense neck and shoulders; no glaring eyes and knitted brow).

In the Alexander Technique, we call this ability to consciously prevent unwanted tension inhibition. It is a skill that is cultivated over time by studying and applying the Technique, and this particular student has developed his ability to “inhibit” quite well.

This redirected thinking made a noticeable difference in the outcome. Much less tension, better precision in execution of the passage.

But then we did something else. We started playing some games with the metronome to “trick” him about his perception of the tempo.

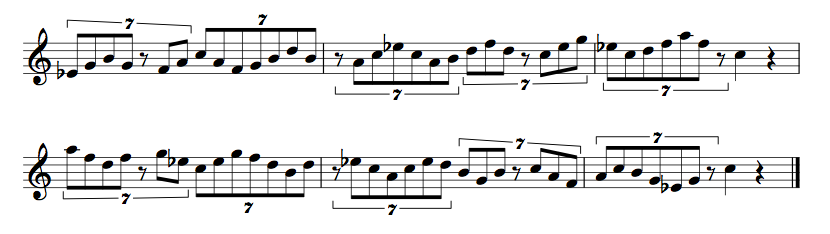

For example, I had him play the passage (continous sixteenth notes in 4/4 meter) as if they were eight note triplets. We started at quarter note equals 130 and gradually moved the metronome tempo upwards. The passage felt to him very easy and clear when approached as triplets. Before long he was playing the passage at quarter note equals 180 with considerable accuracy.

He didn’t have time to do the math to realize that he was actually moving the notes faster than he was able to do before.

I immediately had him go to quarter note equals 138 and play the passage as it was originally (in sixteenth notes). He was able to play easily and consistently at this tempo. Laughing, he said, “The tempo feels slow now. If feels like I have time to think.” (He laughed because he realized that he just tricked himself in a good way).

This change in his perception of the tempo helped him to get out of his habitual thinking, and helped support his wish to keep the excess tension in check as he played.

In truth, there is no “fast” or “slow” when it comes to tempo. “Fast” is just an opinion (an adjective of judgement, if you will), as is “slow”. There is no absolute measurement for either. All there is is the objective measurement of beats per minute. There is just relativity between tempos.

So when you’re practicing or performing, don’t think, “Here comes the fast part.” All you’ll probably do is tense up unnecissarily and create unhelpful conditions in yourself to play the passage.

Think instead, “I have time.” That will help (if even a little bit) to keep you from going into tense anticipation of the music. It’s this tense anticipation that not only creates mechanical disadvantages in your body as you play, but also, puts your brain into an unclear state of a mild “panic”.

Let go of the idea of “fast” or “slow” and replace it with the more objective and measureable “clicks per minute” on the metronome (or whatever source you’re using to establish tempo).

And by all means, start using the metronome in such a way as to keep you thinking differently in how you perceive tempo and rhythm every day. Using your body well as you play and being flexible in your perception will reward you with measurable benefits.