The language of music. The language of improvisation. The language of Jazz. The language of Bach. The language of Lester Young….What does it mean exactly when we refer to something in music as a language? It certainly means different things to different people.

To some it implies something immediately distinguishable, yet flexible and changing. To others it might mean an exact codification of patterns, harmonic ideas and melodies…”licks”, as it were. I think we use the language metaphor because in music, as in speech, we are hoping to express ourselves, and be understood by others in a clear manner.

It seems natural for anybody studying a particular genre or style of music to spend an extraordinary amount of time studying, listening to, transcribing and analyzing music particular to that genre or style. And for sure, this is a reasonable place to start in order to absorb the so-called “language” and “logic” of the music.

But one of the wonderful things about the modern, living, continuing-to-unfold jazz tradition, is that there is so much room to absorb new languages. Jazz has a rich tradition of this.

Think back to the many different stylistic elements jazz has absorbed: gospel music, field hollers, rural blues, broadway show tunes, modern classical composition, Latin music (everything from Afro-Carribean to South American and beyond), Rock and Roll, Gypsy music (and other ethnic folk musics), just to name a few.

Something that the vast majority of modern jazz innovators have in common was (is) their deep and active interest in music outside of the jazz idiom. Artists such as Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Charles Mingus, Lennie Tristano and Ornette Coleman listened to and studied a vast array of music outside of anything that could be called jazz: from Bach, to Bartok, to West African folk music, to Chinese opera, to Indian classical music, to…

And all of this study and listening added to the uniqueness and expansiveness of their artistic output. It is partly why we find them so unique, so compelling.

So If you have a fairly good handle on the basic elements of jazz improvisation, such as rhythmic control, playing comfortably over chord changes, knowing some standard repertoire, etc., here’s something to consider to make your improvisational language richer, more distinctive and personal: Take a style vacation.

Take a few weeks or even months getting away from actively listening to jazz. Completely. Find some another type of music that lights you up, and spend some serious time with it.

It doesn’t matter what that music is, as long as it is something that really speaks to your heart and mind.

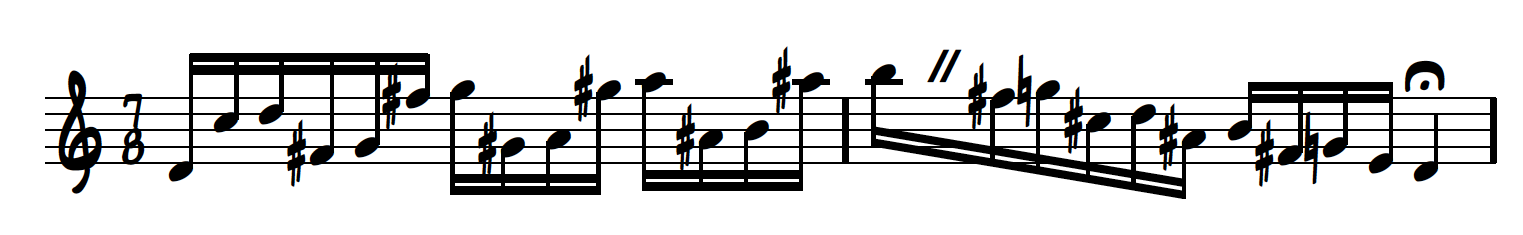

But don’t just listen to the music, study it. Transcribe pieces and solos, and analyze them. Improvise from these pieces as well. Find musical ideas you like and put them in all 12 keys. Absorb the language of articulation, time, Harmony (where applicable) and feel of the music you’re studying. In essence, do what you did (or are continuing to do) with your jazz studies.

I also suggest taking a vacation from practicing jazz. Instead, practice learning to improvise in your newly chosen idiom. Don’t worry, your jazz playing won’t get worse. In fact, it will get ultimately much better. Here’s why:

- You are still engaging your brain in the process of improvisation. The “imagination-to-ear-to-sound” skills are still being called upon in a big way.

- You are developing a different way of thinking about note organization. Again, this is a brain skill that you will bring into your jazz playing with (what I predict) surprisingly good results.

- You are learning to hear music in a different way. If you transcribe, as I’ve suggested, your ears will get huge.

- You are expanding your conception of rhythm and articulation. Though at first it may seem foreign to your jazz playing, it will ultimately enrich and expand it. You will absorb this new time/articulation feel into your jazz playing, and make it a part of your personal language.

- You are learning new forms to improvise over. Whether you are working with closed-ended bar forms, open-ended forms, such as modes, or just free, thematic improvisation, you’ll really broaden your jazz concept by becoming fluent improvising in your new idiom.

- You are learning to imagine your jazz improvisational language in a broader context. Remember that you’ll be bringing your improvisational skills as a jazz musician into a new idiom. This in itself will help you to think differently about how you play.

I have spent various periods in my practice career taking these kinds of diversions, these “style vacations”. Amongst them studying: Balkan folk music, the music of Charles Ives, Cajun folk music, the music of Bela Bartok, Astor Piazzolla and Hank Williams.

I’ve looked at these different kinds of music deeply, with real passion and curiosity. I’ve never consciously tried to apply a single idea or element I’ve absorbed from studying this music, but I always notice how richly different my jazz playing becomes when I return to my jazz studies.

So give yourself a break from your continuous pursuit of the jazz language and style. See what emerges. You might be very pleasantly surprised.