I’m especially pleased to announce that my latest eBook, Four-Note Diatonic Triad Cells: Comprehensive Studies in Leading Tones, is now available for purchase and immediate download.

Major and minor triads are a fundamental building block of virtually any melodic language, most certainly including jazz. As an improvising musician, gaining mastery over the movement and connection of triads is an essential skill that leads to fluency and cogency in musical expression. In bebop as well as the modern jazz languages, this is especially true when the triads can be seamlessly connected via half-step leading tones.

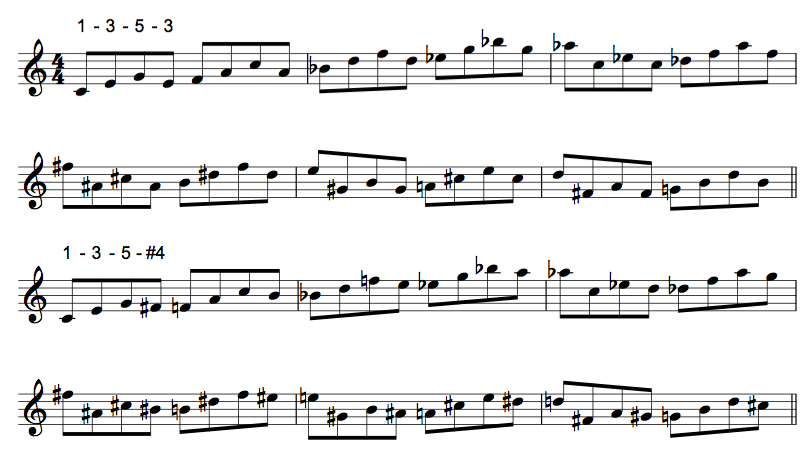

The concept of this book is simple, but far-reaching: I’ve converted every diatonic triad (major and minor, in all inversions) into a “four-note melodic cell” by adding a note that helps it to connect (via half-step voice leading) to other triad cells in a flowing, melodic way. By adding this fourth note, triads become more readily available for eighth note and sixteenth note movement, which is still the rhythmic staple of modern jazz improvisation.

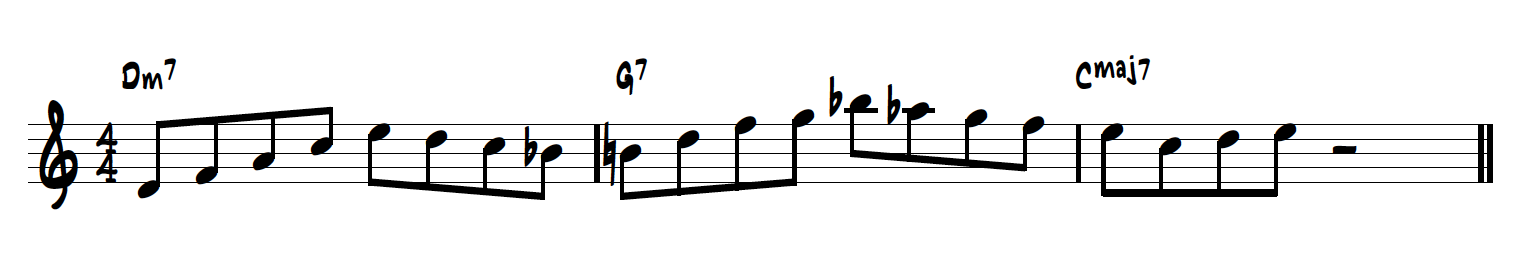

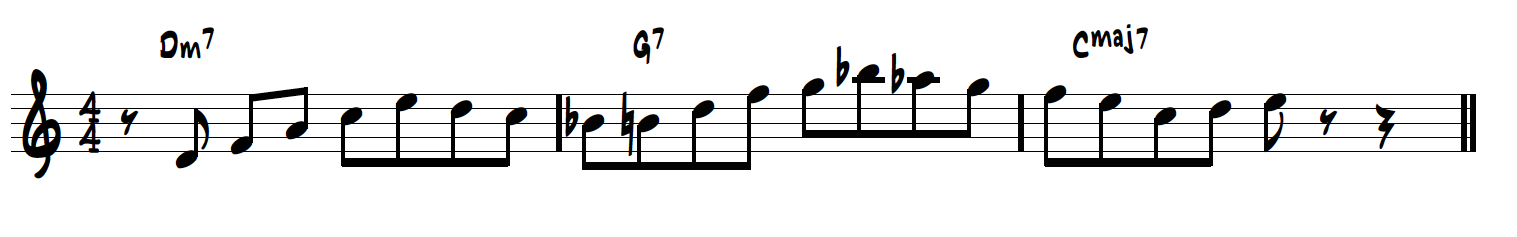

Each triad cell is connected to the next by both lower neighbor and upper neighbor leading tones. The “fourth note” of the cell is either a diatonic tone (either scale degree, or a repeated chord tone), or a chromatic passing tone, depending on how one cell needs to connect to the next cell:

The triads are organized to move intervallically: ascending perfect 4ths (as in the example above), as well as ascending and descending minor 2nds, 3rds, etc., in every possible way. These intervallic movement sequences are organized from major to major, minor to minor, major to minor and minor to major; again, in all inversions and with upper and lower neighbor leading tones connecting them.

Some of these movement sequences will most likely sound familiar (“bebopish”), whereas others will sound most decidedly “modern”. At the end of the book I’ve included a Reference Chapter that demonstrates how each of these triad cell movements can be applied to ii-V7 cycles. Part of my aim in composing this book was to bridge the gap between bebop and more contemporary jazz languages.

You can think of this book as a playable reference, of sorts, on how to connect triads via leading tones. Like my other eBooks, it is comprehensive and very carefully organized and presented. There are over 200 pages of notated exercises to keep you busy for a very long time. I’ve composed each exercise to flow in a smooth, melodically logical way.

Working from this book will not only significantly increase your melodic fluidity when improvising, but will also improve how you hear and think harmonically and melodically. You’ll have a working guide on how to go deeper into using melodic devices with triads, including triad pairs, stacked triads and enclosures.

And as a bonus, practicing these exercises on a regular basis will significantly improve your technical skills, no matter which melodic instrument you play. You’ll be working with arpeggios in a fundamentally different way: One that is challenging, enjoyable, and ultimately, highly practical.

I’ve written this book with the intermediate to advanced jazz improviser in mind (for this reason I don’t explain basic jazz harmony and theory), though even less advanced students of improvisation can benefit from working through these exercises by getting the sounds in their ears and under their fingers. All exercises are in treble clef.

So take a look at the Four-Note Diatonic Triad Cells: Comprehensive Studies in Leading Tones landing page on my blog, which has a pdf sample of one of the exercises, as well as a pdf copy of the written introduction of the book, which further explains the concept, the format, the benefits and the practice guidelines for implementing the work. I’ll also be putting up a few jazz etudes that deal specifically with this concept in the near future. Hope you enjoy, and let me know what you think!