There is a common, often disconnecting, conception many musicians carry with them when they first seek my help as an Alexander Technique teacher:

In essence, they believe that the very problem that brought them to me is of a purely physical nature. Put more precisely, an issue of muscle function.

I call this a “disconnecting conception” because not only is it untrue, but it also tends to harmfully divide and separate them from themselves as whole beings.

You see, in truth, nothing you do when you play music is “purely physical”. Thought (both conscious and unconscious) impacts all of the physical manifestations of your music making.

Now, to be sure, most of the specific fine motor skills you’ve acquired as a musician can be called upon with minimal thought, or even below consciousness. (Some folks refer to this as “muscle memory”, a not particularly accurate description of the phenomenon.)

But these motor skills can be modulated significantly for better or worse (in the moment!) just by changing your thinking. (You’ve no doubt experienced this countless times.)

F.M. Alexander (the founder of the Alexander Technique) had a more complete term to describe not just musical performance, but all human activity: psychophysical.

In dealing with his own rather serious issue of losing his speaking voice during performances (he was a stage actor), Alexander came to realize that the physical manifestations of his problem (excessive misdirected bodily tension) were inextricably linked to how he thought about using his voice while acting.

It wasn’t simply a “matter of muscle”, so to speak. It was a matter of mind and muscle, the relationship between thought and action. (Hence, the term “psycho-physical”.)

This isn’t such a foreign concept to grasp for most musicians, as “focus” and “intention” both play a significant role in success in both performance and practice.

Yet, I’m still surprised at the amount of rather highly skilled musicians who have a tendency to reduce the acquisition of technical skill to purely physical, muscular exercise.

For example, I’ve encountered brass instrumentalists who routinely practice long tones while watching television to “bulid strength”. Or woodwind players silently practicing fingering exercises (without blowing) as they listen to music to cultivate “muscle memory”.

This practice habit, in my experience both as teacher and as musician, is inefficient, and only marginally helpful (at the very best!)

At worst, it can also be counterproductive, and sometimes even harmful. This is because it is an invitation to develop unconscious patterns of inefficient bodily use and sub-optimal coordination. Often these patterns become gradually ingrained into what the musician thinks it should “feel like” while playing.

As I’ve mentioned in previous blog posts, strength and coordination are inextricably linked, but coordination takes precedent over everything.

Mindless, repetitive actions might build a certain amount of muscular strength specific to the particular technical challenge you’re addressing on your instrument, but strength without coordination is functionally useless.

That’s a simple truth for any activity.

So rather than exercising muscles as you work on improving your technique, think instead of exercising your coordination. And not just the coordination of your fingers (and lips, tongue or any other part of you that is directly involved in playing your instrument), but the coordination of your entire self.

See that you aren’t compressing yourself as you play. (Avoid pulling your head down into your spine, stiffening your shoulders, locking your knees, etc.) Take time to notice this misdirected tension and energy and work toward gradually reducing it. Integrate that awareness consciously into your intentions to improve your technique.

Notice where your attention goes, both when you’re playing well, and when you’re not playing so well. As you notice the shift in your attention, you can also notice how your entire body changes (see above).

Give yourself a chance to stop and redirect your efforts. Make sure you’re clear about what you want (your sound, execution, etc.) and just as important, how you are “using yourself” to get what you want.

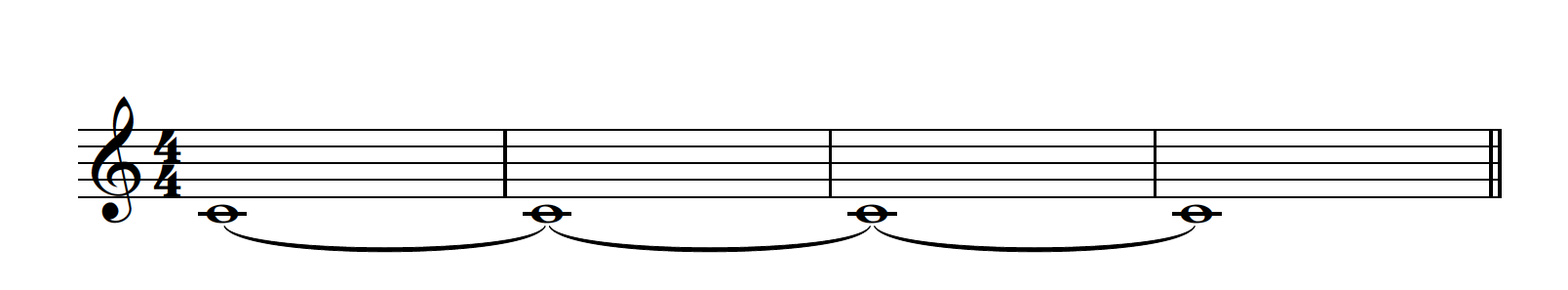

And, of course, make it musical. Give whatever you practice some sort of musical intention and imagination, each moment you practice it.

If you work each day to observe and more effectively integrate your thinking into your playing, you’ll find that not only do you improve more steadily, but that you don’t even need as much time as before making mindless repetitions in order to build “muscle memory”.

A few moments of mindful work will always take you further toward your goals than an hour of mindless “exercise.” It always works this way for me and my students, and mostly likely will work this way for you. Give it a go!