Freedom is the capacity to pause in the face of stimuli from many directions at once and, in this pause, to throw one’s weight (put one’s intentions) toward ‘this’ response rather than ‘that’ one.

-Rollo May, existential psychologist, from his book ‘Freedom and Destiny’

One thing that virtually every musician has to do in order to improve is to change what they are currently doing. This might mean changing your practice regime, changing your understanding of your instrument and pedagogy, changing your perception of sound, changing your quality of attention, etc.

It might also mean that you have to change the postural and movement habits you bring to playing your instrument.

Habits of breathing, standing and/or sitting, how you use your arms and hands, how you balance (or not), how you use your other senses, etc. It’s entirely possible (and even highly likely) that you are sometimes misdirecting your efforts in these areas as you play.

The Alexander Technique is a practical method of helping you to change your postural and movement habits for the better. And one of the most essential tools of the Technique is known as “conscious inhibition” (most students and teachers of the Alexander Technique just refer to it as “inhibition”).

In the simplest sense, inhibition is your ability to consciously prevent yourself from reacting in an habitual, unwanted way. Unwanted tension in your neck. Unwanted rushing of the tempo. Unwanted stiffening in your shoulders, Unwanted gasping as you breathe, etc.

By keeping the unwanted things “in check”, you are free to pursue what you do want in a way that is more in accordance to your human design. You increase your odds for success.

From a neurobiological point of view, all skilled motor activity requires a balance between “volition” (muscles going into the desired, or helpful action) and inhibition (muscles refraining from undesired, or unhelpful action). Most inhibition in skilled activities takes place naturally and unconsciously (as it should).

But sometimes you need to use inhibition in a more constructively conscious way in order to improve things.

Unfortunately, there can sometimes be a misconception about using inhibition consciously. To many people, conscious inhibition means “trying” to stop something from happening. It is exactly this “trying” part that can too often create a whole other set of problems when setting out to change movement and postural habits.

“Trying” sometimes means that you are struggling to stop yourself from doing what you habitually do. As if you have little or no control over it. Here’s something F.M. Alexander (the founder of the Alexander Technique) said about it:

When you are asked not to do something, instead of making the decision not to do it, you try to prevent yourself from doing it. But this only means that you decide to do it, and then use muscle tension to prevent yourself from doing it.

But that’s not at all the way inhibition is used in the Alexander Technique. Rather than “trying to stop” something, you learn to simply decide not to do it.

I know, I know…more easily said than done, especially when you have a deeply ingrained habit attached to playing your instrument. But still absolutely doable. That’s the skill you develop by studying and applying the Technique.

The first step in learning to use inhibition in a constructive way, is to embrace the pause.

It is within this brief instant before taking action that you can choose to redirect your attention and clarify your intention and effort. In that moment you come face to face with your habitual reaction, and can give yourself a chance to say “no” to it.

You can decide not to do what you habitually do. And that’s where the magic lies.

Because if you decide not to react habitually you leave yourself free to find other ways to react. You move from habit into the realm of choice.

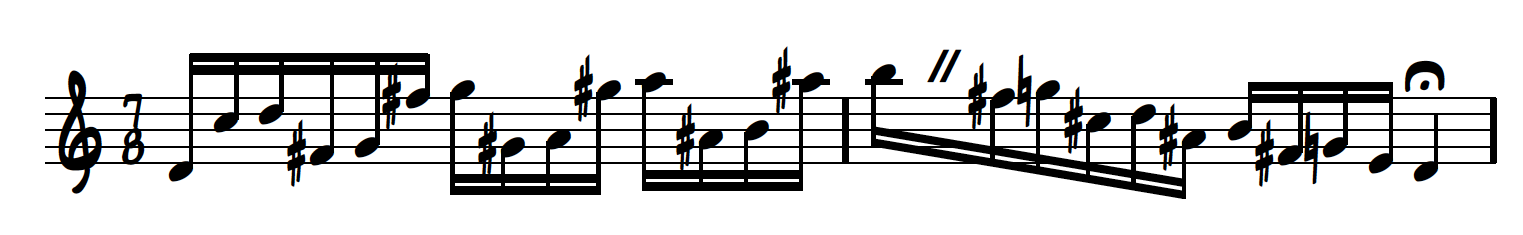

It is the discovery, exploration and embracing of the pause that has given me tremendously powerful tools in managing (which I do quite well!) the focal dystonia in my left hand.

Without using the pause as tool for change, I wouldn’t be able to play saxophone at all any more with any kind of reasonable skill and control. Nowadays, I’m playing better than I ever have, thanks to the power of pausing and redirecting my attention. That simple.

But I gained so much more from the using the pause than improving the functioning of my left hand. Using the pause has helped me to practice everything I practice in a much more constructive, efficient and clearly intentional way.

And as an improvising musician, learning that I can pause, that don’t have to fill every second of my solos with sound, is liberating, and (at the risk of sounding dramatic) has been life changing for me.

I listen at a much deeper level when I play with others than I ever have before. I play with greater empathy, confidence, authenticity, passion, creativity and satisfaction.

All thanks to becoming more and more skilled at pausing.

And to be clear, “pausing” is not the same as “hesitating”. Pausing invites calm, reassured choice, where hesitation invites conflict, misdirected effort and a lack of confidence and clarity.

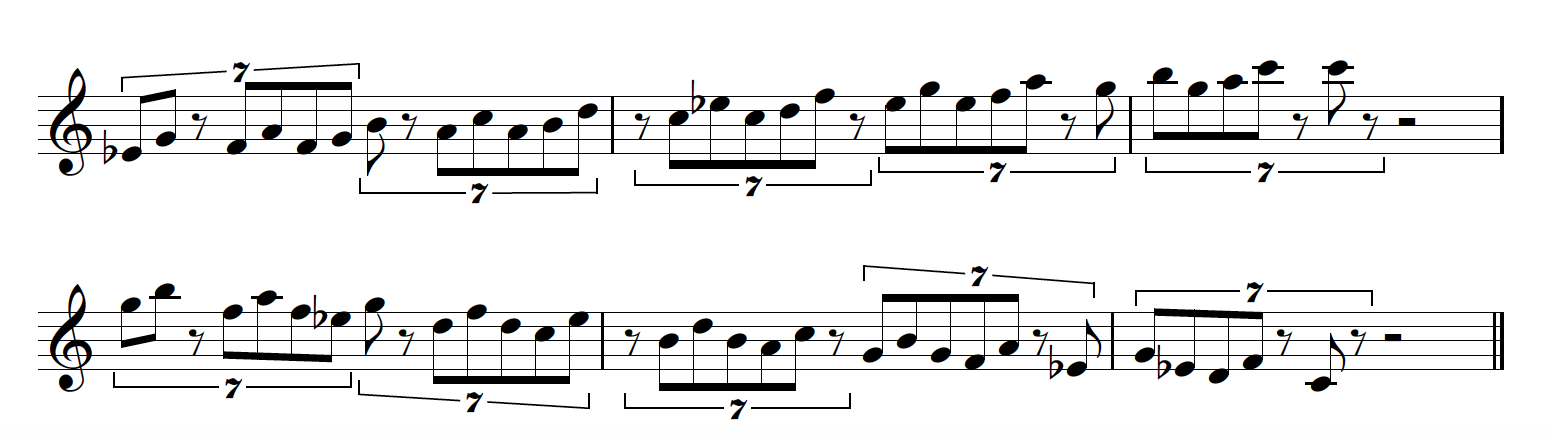

I use the pause countless times every day that I practice, and I bring it with me to rehearsals and to the bandstand.

When I’m practicing, sometimes I pause between iterations of something challenging that I’m practicing. Just a split second to stop and redirect my efforts makes all the difference.

And even in the middle of a performance, the “imagination” of the pause is always there, reminding me that I have more choice than I might have perviously thought.

So I encourage you to explore the pause. Before jumping right in to “fix” what you didn’t like about what you just played in your practice session (by starting over with the same misdirected effort that led to your dissatisfaction), give yourself a chance to stop, find ease and balance in your body, clarify what it is you want and don’t want, and begin again.

As I’ve said in some of my other blog articles, you’ll never waste time when you give yourself a chance to stop and consciously redirect your efforts. Embrace the quiet power of choosing to pause. Respond rather than react, and reclaim your freedom.