In my experience as an Alexander Technique teacher, I find that a significant contributing factor to many musician’s problems is a misunderstanding of how their bodies work with respect to playing their instrument.

I’ll see, for example, flutists who strain as they try to bend fingers where there are no joints. I’ll see pianists trying to use their necks to lift their arms. I’ll see brass players trying t0 “push the air from the diaphragm” even though this is physically impossible (the diaphragm, which is a muscle, releases on the exhalation).

These are examples of what F.M. Alexander (founder of the Alexander Technique) would call erroneous preconceived ideas about the use and the functioning of the body.

Your brain actually creates a representation of the size, structure and functioning of the muscles, bones and joints in your body. One thing that many postural scientists assert is that this representation always trumps reality.

In essence, this means that you will try to move in accordance to how you believe your structure works, whether that belief is based upon truth or fallacy. (Again, you’ll strain trying to bend at joints that don’t exist, for example)

Of course, much of this “belief” (or misunderstanding) is on an unconscious level, and has been cultivated by a lifetime of habit. Equally unfortunate, some of this belief is conscious, due to misinformation. Too many times I see musicians creating excess strain as they try to carry out some bad (anatomically counterproductive, if not impossible) advice given to them by their music teachers.

But whether below the level of consciousness or not, the unfortunate truth for musicians is that this misconceived sense of self, multiplied by thousands of repetitive movements everyday (practice), leads to strain, injury, poor coordination and inconsistent technique.

The good news is that you can change your misconceptions about how your body works. You can learn to move more in accordance to the design of your structure as it relates to gravity.

How? Start by gaining some knowledge. Get a basic understanding of the structure and functioning of your musculo-skelatal system. Look at pictures from anatomy books and study the structures. Experiment with your own body to find where your joints are and how they work.

I’ve come across a tool that is highly useful for helping you to gain a clear and accurate understanding of how your body functions as you move and maintain posture. It is a marvelous DVD produced by Barbara Conable (edited and narrated by Amy Likar) entitled Move Well, Avoid Injury: What Everyone Needs To Know About The Body.

Barbara and Bill Conable are both Alexander Technique teachers, and have developed a method they call Body Mapping to help musicians (and non-musicians alike) to gain a practical understanding of how their bodies work in movement and stillness. Amy Likar is an Alexander Technique teacher and a professional flutist.

This clearly narrated, logically organized presentation has 2 hours of absolutely essential information. Each chapter has lively animations and images that give you an easy way to understand, visualize and clarify your own body map.

It is organized in chapters covering such important topics as:

- Balance-the physiological components that help us maintain our upright stature

- Arms-thorough explanation and demonstration of how your arms (including your wrists, hands and fingers) work in relation to the rest of your body

- Legs-besides examining the structures of the legs (pelvis, too), this chapter helps you to understand your legs in relation to your arms in moving and maintaining balance

- Breathing-really demystifies so much of the conflicting information about this too often misunderstood function

- Inclusive attention-how your other senses are integrated and impact how you move and maintain posture

The other chapters are equally interesting and helpful, addressing specifically the issue of how our body maps become flawed, and how we can correct them.

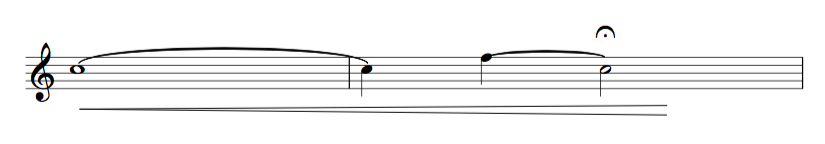

Here is a sample video demonstrating the rotation of the lower arm:

If you’re a musician, you will be nothing but helped by viewing and studying this video. If you teach music, you owe it to your students to have a reasonably clear understanding of the type of functional anatomy and physiology presented in this program. Not only will you give them accurate information, but also, you’ll be able to help them to prevent many of the harmful habits that come from these misconceptions.

I own the DVD, have spent many hours with this material, and highly recommend it.

Clarifying your body map won’t guaranty that you’ll solve all your movement and coordination problems as you practice and play music. Because your habits often feel “right” to you, it can be difficult to sense the misdirected energy and tension that comes with a poor body map (this is where a skilled Alexander Technique teacher and/or Andover Educator can help).

But just gaining the right information, studying it and applying it to what you do can make a huge difference. As I said, it’s a great place to start. I’ve seen some of my students improve instantly and significantly just be rectifying a particular misconception about their bodies as they play their instrument.

And that reminds me of this “oh, so true” aphorism by F.M. Alexander:

“We can throw away the habit of a lifetime in a few minutes if we use our brains.”

No doubt.