One of the things that many great musicians and music teachers seem to agree upon is the value of practicing slowly. Whether working on technique or improvisation, it is now almost cliche (yet true!) to say, “If you want to speed it up, you first have to slow it down.”

Slow practice really can prove quite beneficial. Here’s a few reasons why:

- It gives your brain a chance to process information more precisely and lucidly.

- It gives you a chance to become more conscious of any habits you might have that interfere with your ability play (so you can prevent them).

- It strengthens your emotional connection to the music (even if you’re “just playing scales”) so that your ability to express yourself becomes second nature.

- It allows you time to make aesthetic decisions that you might otherwise overlook at fast tempos (this is especially true in improvisation).

- It increases your rhythmic precision.

- It deepens your kinesthetic experience of making music.

All good stuff. Here’s a really nice video by clarinet virtuoso Eddie Daniels talking about how he uses slow practice to increase the precision of his technique at fast tempos:

But as an Alexander Technique teacher specializing in working with musicians, I sometimes encounter students who actually make their technique worse rather than better by practicing slowly. They do so because they lose sight of the main aim of slow practice: to learn how to move from note to note through release and balance.

When I encounter such a student, I see lots of tension and holding as the tempo slows down. Often, I see more strain and imbalance at the slower tempos than at the faster ones.

This is usually because the student’s aim of self-awareness (a good thing) has morphed into self-consciousness (not such a good thing). Self-awareness is about discernment (observing objective information), whereas self-concsiousness is more about judgment (going straight to assigning value to what you’re doing).

With self-consciousness comes a sense of needing to do things “absolutely right”. With this attitude comes fear. And with fear comes tension and holding (an unwillingness to explore, move, or take chances).

What I typically notice in these cases is that the students are dividing their attention in such a way as bring far too much awareness to one part (the fingers, for example) at the expense of excluding the rest of themselves. Lot’s of “forcing” the fingers into control. Too much expectation, not enough exploration.

Part of my job with these students is to help them redirect their thinking as they practice slowly (or at any tempo, for that matter). They learn to notice themselves in a broader light, expanding their awareness of themselves, and clarifying the conception of how their entire body (including their senses) is integrated and involved in the music making process.

With this expanded awareness (along with a diminishing self-consciousness) comes a complete shift in the aim of slow practice. The old aim being to “control” the fingers. The new aim being (as I mentioned above) to move from note to note through release as they maintain an easy, upright balance.

When this shift of intention occurs, marvelous things begin to happen: Technique becomes cleaner. Velocity increases with ease. Rhythmic accuracy improves. Self expression deepens. Confidence increases.

So if you devote some of your practice time to slow, mindful work (or would like to start), here are a few things to aim for to help you optimize your endeavor:

- Start in balance-Notice how you’re maintaining balance. Are you stiffening and holding, or releasing and returning to an expansive, elastic, natural poise? Let your neck and shoulders stay free and easy as your head balances on top of your spine. Allow your hips, knees and ankles to be free. Let your weight pass into your feet. Breathe easily, quietly and naturally.

- Move by releasing-Going from note to note means releasing muscles first. Think about where you can release as you change notes. When raising your fingers, think about them as releasing away from the keys as you play, as opposed to “lifting” your fingers by creating tension. When attacking a note, think about releasing your neck and your breath.

- Broaden your awareness-Don’t get stuck putting all your attention onto one part (e.g. don’t place all your attention on your fingers). Let your awareness expand to the rest of your body, and your environment. Notice how your entire self is involved in playing the music.

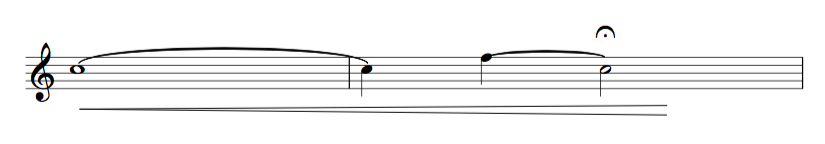

- Give yourself a chance to deepen your kinesthetic experience-Take plenty of time to stop and sense what’s going on as you play. Really embrace the experience of starting from release. Let yourself know deeply, where and how you “land” on the notes (see the video, above).

- Listen to the clarity of attack, tone and time-There is always a temptation to rush the tempo when playing slowly. Avoid this trap by really listening and waiting. Use a metronome and let the time carry you forward easily and precisely. Be still but mobile and fluid as you wait for the click of the metronome. Let the clarity and consistency of your attack and tone be your guide.

- Keep unnecessary effort in check-Return frequently to the question of effort and tension. “Am I beginning to stiffen myself as I go from one note to the next? Am I pulling myself out of easy balance? Am I letting my breath flow freely? Am I waiting for the metronome?”, etc.

This is a fascinating post, Bill. I’ve recently been experimenting with the metronome when practicing, and also with playing slowly. I find that if I start tensing up while I’m playing slowly, it is generally because I have forgotten that the playing slowly is a means to an end, and not an end in itself. That is to say, I have a goal that I want to achieve, and playing slowly is the process I have chosen to use to take me towards that goal. But it can be all to easy to allow one’s goal to slide, and to find oneself focused on the playing slowly.

So, in addition to the helpful points you’ve raised, may I be so bold as to add one more? It is this: frame and hold in mind the reason why you have chosen to play a piece slowly. Remember the goal you want to achieve.

Thanks for writing such thought-provoking posts. It really helps me to clarify my thinking around what I do with my recorder as I play – always a beneficial thing!

Wonderful insights you’ve shared here, Jennifer. I especially like this one: “I find that if I start tensing up while I’m playing slowly, it is generally because I have forgotten that the playing slowly is a means to an end, and not an end in itself. That is to say, I have a goal that I want to achieve, and playing slowly is the process I have chosen to use to take me towards that goal.” Brilliant! I also agree with your suggestion to hold in mind the goal. Without that, slow practice can become yet another drudgery. As I stated in my post, the aim is to “move from note to note through release in balance”, but I never mentioned the importance of the individual musician’s goal (the specific reason for choosing this means of practice). Thanks for that!

One of the useful ways I’ve conceptualized “slow practice” is to think of it not as “painfully slow, forced, and detailed” but as bullet-time practice. That seems to get my head to understand what I’m really doing here, which is slowing down time while keeping my brain moving forward at the normal rate. It helps me, anyway. 🙂

Hi Janis, I really like your idea of “slowing down the time while keeping my brain moving forward at the normal rate”. This, in many ways is a primary aim of slow practice. What happens with too many musicians who practice slowly is that they go into their habitual thinking pattern of slowing their senses down to match the music. Not only is this tedious and, as you say “painfully slow, forced, and detailed”, but also, it doesn’t achieve the benefit to be had from effective slow practice. Thanks for your input!

thanks !

You’re welcome! Hope it was helpful.