In my experience teaching the Alexander Technique to pianists, string and woodwinds players, I often encounter a similar kind of counterproductive thinking concerning the hands and fingers. Specifically, too much attention is placed upon what the hands and fingers are doing.

Not only does this divide the musician’s attention, often cutting off the awareness of what’s going on in his/her body as the music is being played, but also, it interferes with hearing pitch, timbre, and perceiving time clearly.

And sadly, all this attention on the fingers doesn’t even make them work better. Quite the contrary.

Here are a few examples of the kinds of problems with hyper-awareness of the fingers that I’ve come across with my students:

- A saxophonist who is consciously trying to keep his fingers very close to the keys (in an effort to not “waste” movement and play more “efficiently”). In doing so, he makes his entire body stiff and his fingers sometimes can’t move in response to the demands of the music. He’s stuck.

- A pianist who stares constantly down at her hands as she plays, making sure her fingering is “correct” as she plays an unusually high percentage of wrong notes on a piece that she knows quite well.

- A violinist who can’t keep his eyes off his fingers for fear of playing out of tune. (Ironically, as soon as he takes his eyes off his hands, his pitch improves dramatically.)

The simple truth is that if you want to improve how your hands work as you play, you have to leave them alone, so they can do the right thing without interference. To do this you have change your thinking. You have to replace the thought of your fingers “doing the right thing” with a broader kind of thinking.

First, start with the aim of being free in your body as you play. In particular, ask yourself for freedom in your neck, shoulders and back. This alone will not only change the quality and quantity of muscular tension as you play, but also, will calm and center your mind and improve your breathing.

Make this a top priority as you practice. The freer you are in your head, neck and back, the freer your fingers are to move and create the stability necessary to play your instrument. This is something you’ll need to practice as you practice (yes, I meant to say that). Here’s a previous article I’ve written about practicing paying attention to help you with this.

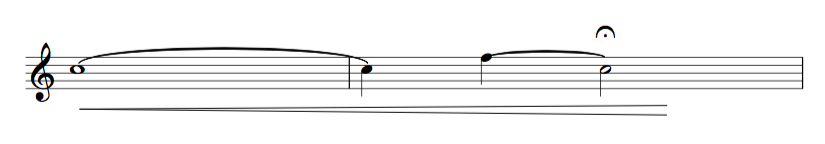

Next, rather than trying to feel how (or what) you think your fingers need to feel, think instead of where your fingers need to go as you play from one note the next.

By taking your attention from what you feel to where you are going, you increase your spatial awareness (and improve your sense of time, as well). Your brain organizes the music making task in a fundamentally different way, allowing your fingers to move freely, easily and quickly. In the simplest sense, you get out of the way of your brain’s ability to organize and control complex movement, so it can do what it needs to do unimpeded.

This is something that can be practiced gradually, using simple visualization:

For example, if you’re a saxophonist, practice a very easy, familiar pattern (arpeggio, scale, intervals, etc.) at a slow tempo as you think, not of what your fingers are doing, but what keys need to be pressed and/or released as you go from note to note. Think ever so slightly ahead to the next note to be played as you land on each note. If you practice this regularly, you’ll learn that you can play rapid passages that you couldn’t play before with stunning ease and clarity. (Same general idea if you play piano, strings, etc. Think where on your instrument you want your fingers to land, not what your fingers have to do.)

Finally, replace the thought of fingers with tonal imagination. Practice singing passages or patterns that you find difficult on your instrument. First, sing the passage slowly and very precisely, making sure the sequence of pitches and the rhythms are crystal clear in your mind. Once you’ve accomplished that, play the passage by following your ear. Really hear the passage clearly in your mind, and don’t worry about what your fingers have to do.

Most of the chronic technical difficulties musicians struggle with are a result of tense anticipation. Hyper-awareness of the fingers is akin to driving a car on the highway at top speed with your eyes planted downward on the road in front of you. Scary and stiff. Same thing on your instrument.

So change how you think about your fingers. Practice consistently shifting your attention from your fingers to your broader senses, and you’ll be surprised how limber and accurate your technique becomes.