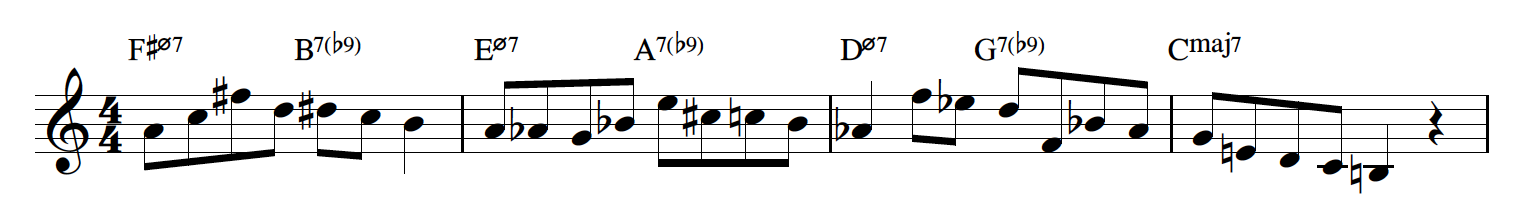

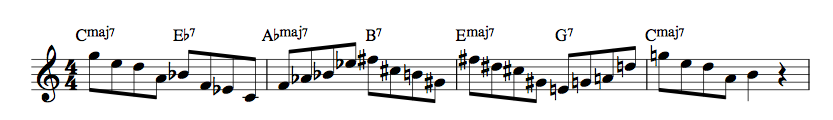

Here’s a line that is inspired by Stan Getz’ classic solo on Stella By Starlight (from the album, Stan Getz Plays, where he so masterfully uses polymeter to create an interesting rhythmic tension in the final cadences of the song form on the first chorus). The harmonic structure I’ve used here is a minor to major turnback (i.e., minor key ii-V7s that “turn back” and finally resolve to major), which also happens to be a somewhat condensed version of the last eight measures of Stella By Starlight. Take a look at the example above. If you analyze the note choices I’ve made on each chord, there is nothing harmonically complex or “exotic”. In fact, most of the melodic content is more or less outlining the chords themselves.

But what gives this line its particular surprise is how I’ve used rhythm and meter in constructing it. The first motif is a 5/4 pattern, subdivided into 3/4 and 2/4 (the 3/4 being the first six eighth notes; the 2/4 being the quarter note and the two eighth notes that follow it). The final two eighth notes of this motif (A and Ab) act as “approach notes”, or passing tones, that lead to the “G” in the second beat of the second measure, thus starting a similar melodic pattern (with some variation) of the original motif, but modulated down a whole step with respect to the new chord (E half dim7). The original rhythmic pattern (six eighth notes followed by a quarter note and two eighth notes) is then stated again, but this time displaced by one beat (hence, the 5/4 over 4/4).

You’ll notice that the quarter note has been rhythmically displaced, moving from beat four in the first measure to beat one of the third measure. On the third beat of the third measure the rhythmic pattern varies again, but still implies a 5/4 organization, with the B natural acting as the fifth beat of the 5/4 pattern. So the entire pattern fits into 15 beats, giving the impression of the time turning around significantly against the 16 beats of the four-bar harmonic form. Spelling out the C maj7 gives the entire melodic line a strong sense of release against the previous harmonic and rhythmic tension. If you practice this over a backing track you’ll most clearly hear the harmonic/rhythmic tension, but even practicing it with a metronome clicking on beats two and four, you’ll still get the feeling of the cadences being displaced against the 4/4 form.

If you would like to explore these concepts further, please consider my e-books, Essential Polymeter Studies in 4/4 for the Improvising Musician, and ii-V7-I: 40 Creative Concepts for the Modern Improviser. For a free, downloadable pdf of this etude, click the link below: