“If you make a mistake, you might want to play that…”

-Miles Davis

I’ve been teaching the Alexander Technique since 2009 at AMDA College of the Performing Arts in Los Angeles.

For every class that I teach, I always arrive with a fairly well detailed lesson plan. In my 10 years of teaching I’ve never once stuck to my plan.

Yet I still continue to formulate a plan and bring it with me to every single class.

And every day for the past many years (too many for me to remember), I start each of my daily saxophone practice sessions with a fairly well detailed practice plan. In all these years of practicing, I’ve never once stuck to my plan.

Yet I still continue to formulate a plan and bring it with me into the practice room.

Why (you might ask) would I do this? Why would I expend time on something that, ultimately, I won’t use?

Well, the truth of the matter is that I always use my plans.

Just because I don’t stick to them doesn’t mean they’re not of great value to me, both in teaching and in learning.

So let’s go to the more fundamental questions here:

1. Why make a plan in the first place?

2. Why don’t I adhere to my plan?

Why make a plan in the first place?

Because making a plan clarifies and details my intentions. These intentions are drawn from what it is that I’d like to accomplish/address. This is always based upon my experiences from the pervious session (whether in the classroom or practice room).

So I begin each session without ambiguity, without hesitation. I immediately start my work efficiently and purposefully. Minimal “wasted” time/energy, optimal engagement/presence.

All good, yes? So then…

Why don’t I adhere to my plan?

In a word: flexibility. As important as my intentions are, I must remain ever vigilant to what is actually needed in the present moment. And that requires an ability to be open to the possibilities of altering my previously intended course of action.

This, to be sure, involves balancing on a fine line. It means staying committed to doing the thing that is most helpful, whether this falls inside or outside of my plan.

It means staying always mindful of my plan (my experience-based intentions), but being willing to let go of some (or all!) of it, too. It means, sometimes, that I come up with an entirely new course of action right there in the moment.

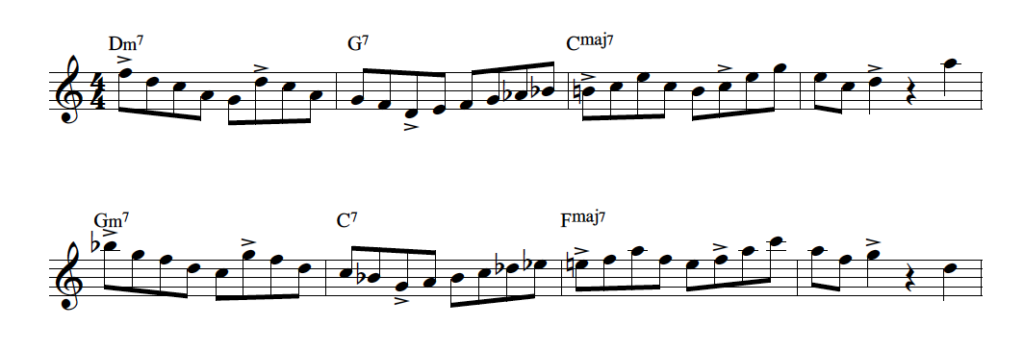

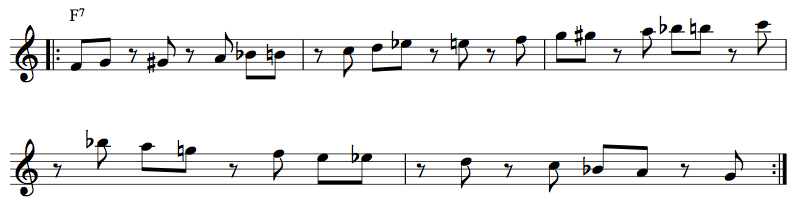

If you’re an improvising musician, you probably already see this attitude as being analogous to improvising music. There is form, perhaps even some kind of a planned sequence of events.

But often, the real magic happens when we deviate from the plan.

Yet this deviation could never occur without a plan in the first place. (I actually think the reason jazz musicians enjoy improvising over standard songs, in part, is to have a “plan to push against”.)

So when you practice do you have a plan? If so, what is it based upon? Are you flexible with it? If not, why not?

And if you don’t have a daily plan when you practice, consider changing that habit. You can always alter (or even abandon) the plan. But you will start each practice session with clarity, curiosity and accountability. You will work toward your goals in a conscious and onstructive manner, always building collectively from previous experience.

Work toward making your plan as detailed as is most optimal for you. Too much detail (or too many tasks)? Simplify. Prioritize and let the things go that seem least essential. What seems to work? What doesn’t?

Not enough detail? Start filling in some blanks. Add more tasks. Ask more questions:

“What do I want? What do I need to work on to get that? What is standing in my way right now?” What can I let go of?”

Take time to formulate and write out tomorrow’s plan at the end of today’s practice session.

Get to know yourself and your music ever more intimately. And enjoy the process!