It’s an exciting time right now in modern jazz. There are some younger artists (younger than me, anyhow!) who are cultivating unique, highly personal voices.

As a tenor saxophonist, I think of artists such as Mark Turner, Chris Potter, Melissa Aldana, Matt Otto, Bill McHenry, Ben Wendel, Joel Frahm and Donny McCaslin (to name but a few) as examples of an ever-expanding lexicon in the great jazz tradition.

All of these artists are very sophisticated harmonically, pushing the boundaries of extension and substitution over song forms. Usually when I hear other musicians marvel at their sophistication, it usually starts and ends in the realm of pitch choices.

But these artists have another thing in common: They all have a highly cultivated rhythmic imagination.

I say highly cultivated, because it’s unlikely that this happened by accident. That is, it’s more likely that there has been conscious attention (through practice and study) brought to the rhythmic aspects of their improvisational languages.

Whenever I listen to a Mark Turner solo over a standard song, I’m struck by the unpredictability of his phrasing. It’s as if time gets suspended as he’s playing in time. Lots of phrases “ignoring the bar line”. Lots of rhythmic complexity, such as polyrhtythm, polymeter, metric modulation, etc. Lots of freedom…

And the beautiful part (to me, anyhow) is it sounds like he’s just playing, just expressing himself in the moment. His rhythmic approach sounds so highly developed that it seems unconscious. It is something that serves his spontaneous self-expression.

There is a huge amount of emphasis on ear training (for pitch) in jazz improvisation, and rightly so. The idea, like Sonny Rollins said, is to “access the subconscious” when improvsing. To do this, you have to practice things until they go so deep inside you that you don’t even have to think about them to use them. You imagine, you follow your ear, you play.

This takes lots of discipline, time, reflection and commitment. Any serious student of improvisation knows this.

Most jazz ear training involves learning to identify (and play back) lots of pitch-related things: intervals, scale colors, modes, chord qualities, harmonic movement, passing tones and more.

So it should come as no surprise that the serious improviser (you?) will spend lots of time developing this part of your ear, perhaps by transcribing solos, singing scales and chords, memorizing melodic patterns by ear, and more.

But you have “another ear” that you might not working on as consciously: your rhythmic ear.

Sure, if you transcribe a solo, you’re transcribing everything. But if you analyze this solo, are you giving enough time and attention to how the solo is constructed from a rhythmic standpoint?

Where do the phrases begin and end? How is rhythm used to build meaning and give cogency? Are there any metric modulations? Is there any tension and resolution that is built specifically upon rhythm, rather than pitch?

If you’re not asking these (and other) questions when analyzing a solo, you should. Here’s why:

The most remarkable, most revolutionary thing about the great Lester Young was not his pitch choices. It was his beautiful, floating time feel and his rhythmic sophistication.

A lot of Lester Young’s solos ebbed and flowed with tension and release via the rhythms more so than the pitches. (Don’t get me wrong, he had a beautiful melodic sense, and could aways choose the loveliest of notes.)

He, too, “floated over the bar”, as he used polymeter, metric modulation and other devices to stretch and compress his phrases in unpredictably beautiful ways. It’s no mystery that he is considered the precursor to the “modern jazz” era that began with bebop.

And as bebop developed, there was, of course, a harmonic revolution. The rules for dissonance and consonance, tension and resolution, were fundamentally shaken up in the jazz world.

But there was also a rhythmic revolution. Fast tempos, asymmetrical phrases, metric modulation, polyrhythm…all this became part of the modern jazz language.

Yet, to this day, the rhythmic innovations seem to take a back seat to the harmonic ones.

And that’s too bad, because one of the most identifiable aspects of any jazz artists (besides sound) is phrasing. If you’re just spitting out continuous series of eighth notes as you improvise over a song, that could get old soon, no matter how harmonically sophisticated you play.

But if I can’t predict your phrasing, can’t predict how you stop and start, can’t predict how you connect your ideas, can’t predict what kinds of rhythms are giving life to your ideas…well, then, I for one, am at the edge of my seat giving you all my attention.

So how do you develop a rhythmic vocabulary and a more sophisticated rhythmic imagination (your “other” ear)?

They same way you do your sense of pitch. You listen, analyze and practice. Just like you have to “feed your ears” for pitch, you need to do likewise for rhythm.

Here are five things you can do:

1. Pay attention-Start by changing your approach. As I mentioned above, if you’re analysing an improvised solo, make a conscious decision to do a thorough rhythmic and form analysis. Notice as specifically as possible how rhythm (including space) is used to build tension and move the story along.

2. Seek out the jazz masters-Look for the improvisers whose rhythmic sense is extraordinary. You can’t go wrong starting with Lester Young, and you can go so much further.

3. Look outside of the jazz idiom-Find some improvising musicians in other genres whose rhythmic sense seems so complex, it’s almost baffling (Balkan folk music, for example). Listen to the point that you can sing along. Once you can sing along, take out the metronome and analyze. Then play around with these rhythms (see below).

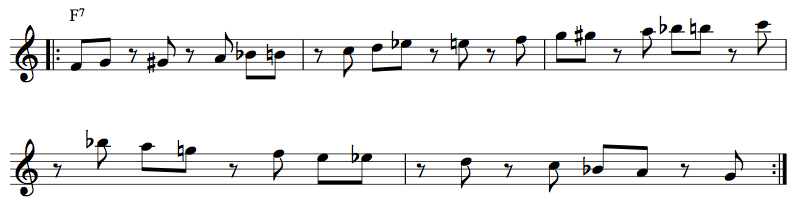

4. Practice using specific rhythms as you improvise-Choose a rhythmic pattern that isn’t readily available to you when you improvise (maybe something from one of the masters mentioned above) and use it to improvise over a set of chord changes, or a mode, scale or motif. Limit yourself to one rhythm at a time. Though it might seem awkward at first, it will go into your subconscious (if you give it enough time and effort) and will become part of your natural musical expression (just like the harmonic material you’ve practiced).

5. Understand the math-Become good at polymeter, polyrhythm and metric modulation. Know how to land on your feet when you go into new, asymmetrical rhythmic territories. For example, If you don’t know how to imply 3/4 subdivision patterns over 4/4 without losing your sense of where the downbeat of beat one is, you’ll never even give it chance to show up in your playing. (I’ve written a very thorough eBook of melodic etudes to help you with this, as well as one to help you with polyrhythm.) Just like you need to understand the “anatomy” of harmony, you need to understand the anatomy of rhythm.

So work on developing “both” your ears as an improviser, and enjoy the surprising changes you’ll hear in your playing.

And if you need help, I offer a highly effective, methodical approach to both improving your sense of time and feel, as well as cultivating your rhythmic skills and imagination. It’s called Rhythm Coach, and it can put you on the path to continued growth and improvement in these areas.