Do you ever wonder why things that you practice sometimes get worse, rather than better, as you practice them? The answer is simple: You gradually worsen the conditions in yourself to play your best.

Simply stated, when you’re playing your best it is largely because you’ve been able to maintain the best conditions in yourself to play your instrument.

One of my Alexander Technique students, himself a highly accomplished saxophonist, related to me a story about working with the metronome to increase his velocity on a particular piece he was practicing:

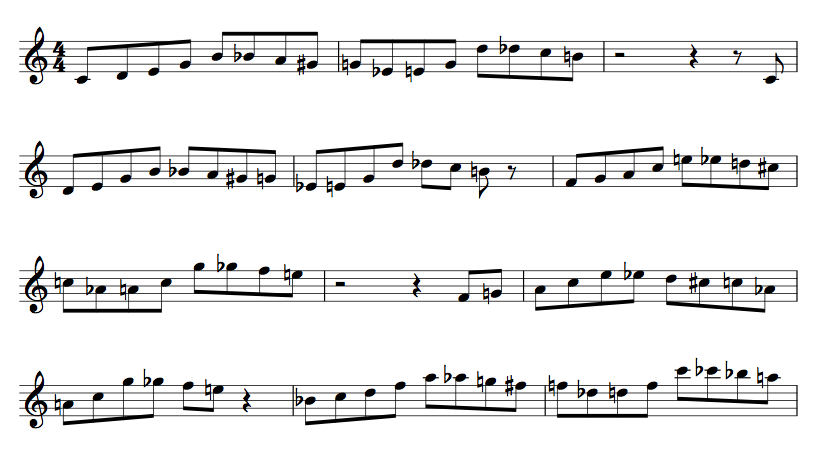

“I was gradually increasing the tempo each time I played through the piece in my practice session. Each time with great results. I was playing freely, easily and accurately. I had worked it up to quarter note = 140. But then, feeling like I wanted to test the waters, I jumped up to quarter note = 160 (the target tempo) and it all fell apart. Not only was I making lots of errors, but also, I was playing with great effort, my breath was no longer moving freely and I felt like I could no longer really hear my sound.”

But here’s where it gets interesting. He continues: “But then when I returned to quarter note = 140, I played just as badly: tense, rushed, unclear tone, lots of mistakes and so forth. It’s as if I had wasted all that practice. Why couldn’t I play at 140, when just moments earlier I could?”

I answered him, “Because you had drastically changed all the conditions necessary in yourself for playing well that you had gradually been working toward. You did this by jumping far ahead of yourself and falling back into your old habits of tension. Then you took those habits and the frustration that comes with them back into your playing at the slower tempo.”

By “jumping ahead” the way he did with the tempo he indulged in something we in the Alexander world call “end-gaining”. (Specifically, placing 100% of your attention and effort on trying for a specific result, as opposed to paying attention to how best to obtain that result.) Because of this he had a difficult time returning to the ideal conditions he had created in himself earlier.

You see, my student started out paying attention to process (in the Alexander Technique we call this paying attention to the “means-whereby”) as he gradually increased his tempo challenges with the piece. Each time he played he was able to use his thinking, to use his conscious attention, to maintain the conditions in himself to play his best at any tempo.

This is what the “means-whereby” is all about. It’s about using your thinking to maintain the best conditions in yourself. The conditions that give you the greatest chance at achieving your desired end.

So what are the “best conditions”? Here are a few of the most essential, from an Alexander point of view:

- Your neck is free-This means that you’re not compressing your head down and back into your spine, nor jutting your head forward. Your simply leaving your neck alone so that it can release your head upward off the top of a lengthening spine. This also means that your jaw is not tense, you are not tightening your face unnecessarily, and that your tongue is free to move.

- Your shoulders (and arms) are free-Your shoulders can release and widen in gentle opposition to your spine lengthening. This will create the best conditions in your arms, and in your hands as well.

- Your back is free and integrated-You are neither arching your lower back (tilting your pelvis forward) nor collapsing and rounding your back. Just let your back stay in neutral as you let your head balance on top of your spine.

- Your knees aren’t locked-No hyper-extended knees (locking your knees backwards). This is something that also interferes with the good integration of your back.

- You are breathing easily and naturally-No noisy and effortful inhalation. Your torso is free to expand in all dimensions to allow your breath to work its best.

- You are not in a hurry– This is perhaps somewhat less tangible, but crucially important. As soon as you get into the “in a hurry mode” you are taking yourself out of the present moment and are dividing your attention, cutting yourself and your good use out of the picture.

When you maintain these conditions, you just plain play better. When these conditions are not present, you not only run the risk of not playing at your immediate potential, but also, of steering yourself toward fatigue and injury.

So what can you do to help find and maintain the best conditions for yourself as you play your instrument?

- Start with your thinking-Every bit of muscular effort you make (whether necessary or not) is conditioned by your thinking. It’s not about your body. It’s about how your thinking is inextricably linked to your body. Always keep this in mind and you’ll avoid the frustration of “my hands just aren’t working today”.

- Learn about your body-Try to gain an accurate understanding of your joints, how your body functions best with respect to playing your instrument.

- Keep the importance of a free and easy use of yourself absolutely primary-It’s not about playing faster, higher, louder, etc. It’s about staying easy in yourself and developing the kind of playing habits that make playing more challenging material easier.

- Be patient-Don’t always try to reproduce what you did on another day. If you could play this piece at quarter note = 160 yesterday, don’t expect to go that fast today when you practice. Expect nothing. Instead, cultivate a “wait and see” attitude. If you always stay with maintaining your good use (the good conditions) your ability to play at more challenging tempos will come as a result. Let there be fluctuations. Accept the present situation.

- Seek help-Because of your habits it can be difficult to get a true sense of what it’s like to create these ideal conditions in yourself. A skilled Alexander Technique teacher can work wonders here in helping you with all the above.

By learning to shift the emphasis from what you do to how you do it, you insure yourself a chance for consistent improvement.